Lightning rod Larry Scott: The heat is on for Pac-12’s controversial commissioner

- Share via

On the first day of September, Larry Scott jetted from the Bay Area to San Diego, feeling urgency to secure a big win.

The public defeats had been piling up during a long month. The Pac-12 announced a football schedule only to postpone its season less than two weeks later. A group of 18 Pac-12 football players, frustrated with the conference’s COVID-19 safety protocols, formed the #WeAreUnited movement, threatening not to play unless they received half of league revenues and Scott agreed to slash his $5.3-million salary by half (he already had cut it by 12% in July because of the pandemic). Scott now was taking heat inside Pac-12 headquarters for fast-tracking bonuses to himself and other executives before announcing layoffs and furloughs for nearly 100 staff members.

The trip south brought fresh hope in the form of a potential partnership with Quidel Corporation, a diagnostic healthcare manufacturer that had developed a daily antigen test for the coronavirus. One of the top reasons the Pac-12 Medical Advisory Board had decided it wasn’t safe to play was the lack of point-of-care testing, and Scott suddenly was in a position to score the supply.

The Quidel flirtation began Aug. 29 and escalated to the point of Scott touring the company’s factory three days later. The man once known as a deft dealmaker was at it again. Scott and Quidel president Douglas Bryant dined outdoors at a restaurant with several of Bryant’s staff, and Scott insisted on staying the night and vetting the product that potentially could save the Pac-12 football season and partly refill schools’ coffers with millions in TV money.

A look at how Pac-12 revenues, spending and distributions to universities compare to the fourth other major conferences in the Power 5.

“I have to admit he was very impressive and decisive, and that gave me the confidence to commit to this endeavor,” Bryant said.

Before Scott left San Diego, the men shook on the terms. Thirty-six hours later the Pac-12 announced the move, with Scott calling it a “game-changer.”

But, while the commissioner took his victory lap during a virtual news conference, his athletic directors were caught flat-footed. Scott had not told them about the potential partnership before the league announced the deal. He later explained that was because of confidentiality issues and the delicate nature of the deal, which would send tens of thousands of tests to college athletes that could have gone to essential workers.

The decision to not loop in campuses, as viewed by people linked to the conference who spoke to the Times, was a step backward for Scott, who has been criticized by some athletic directors throughout his 11 years atop the conference for making them feel disenfranchised and placing them on a need-to-know basis.

One athletic administrator at a Pac-12 school who speaks regularly with Scott expressed disappointment that the commissioner was “secretive” and wondered if it was important for Scott to feel like he was coming to the rescue.

“I very intentionally made it a priority to engage with our athletic directors more. I think our members and I are very pleased with the outcomes of this new approach.”

— Larry Scott

The administrator, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he did not want to comment publicly on the conference’s inner workings, said Scott had greatly improved his communication during the pandemic but stumbled with his handling of Quidel.

These days, even when Scott wins, he can’t shake the cloud of negativity that follows him.

As he approaches the end of his contract in the midst of a series of unprecedented challenges for the conference, interviews with 20 current and former Pac-12 executives, staff and school officials revealed the portrait of a leader who has struggled to build meaningful relationships beyond the university presidents that made him college sports’ highest-paid commissioner despite diminishing returns to their schools.

Some would speak only on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation from Scott, who at this point should be used to the role of league lightning rod as the Pac-12 falls further behind its “Power Five” peers in revenues and reputation.

Conference commissioners aren’t supposed to be household names, but Scott’s inability to ink a deal with DirecTV for Pac-12 Networks distribution shifted attention his way, with millions of fans across the West unable to watch their teams.

His supporters point out that, even if he had that coveted deal, what’s been missing the last decade are dominant programs in football and men’s basketball. The argument goes: if USC football or UCLA basketball were regularly competing for national championships, the noise around Scott would have lessened to a hum.

Instead, Scott has been a walking amplifier, and his detractors say the years have rendered him tone deaf.

But Scott says he has listened better of late, heeding advice to make athletic directors feel a part of the decision-making process. He began inviting them to dinners on the nights before meetings and sending them agendas ahead of time, which he had not done previously.

“Over time as new presidents, chancellors and athletic directors entered our league, there was a shift in views on how we should collaborate together to advance our collective goals,” Scott said.

“I realized that we needed to change our approach. I very intentionally made it a priority to engage with our athletic directors more. ... Our collaboration has been really strong through these very challenging times.”

Scott’s contract expires in June 2022, before the conference’s financial future is put on the line during its next round of media rights negotiations. The league’s deal with ESPN and Fox, negotiated by Scott in 2012 for $3 billion over 12 years, expires in 2024, while the Pac-12 Networks’ cable affiliate contracts end at the same time.

“It can’t come soon enough,” Oregon State athletic director Scott Barnes said.

Here’s why: During the 2018-19 academic year, when the Big Ten distributed $55.6 million to each of its schools and the Southeastern Conference paid out $45.3 million, the Pac-12 sent its members $32.2 million. The Big Ten and SEC are reaping the benefits of their choice to allow Fox and ESPN, respectively, to run their networks, while the Pac-12’s decision to start its own network in 2012 has led to smaller immediate impact.

“There was a lot of praise heaped on the Pac-12 for getting such a great contract [in 2012] and one of the things that got it that contract was going long,” said Oregon president Michael Schill, the chair of the league’s CEO Group. “When you go long, you take the risk of what the market is going to do in the interim. We anticipate when our media rights come up again we’re going to be able to do extraordinarily well, and you can imagine leapfrogging. Right now we’re in the unpleasant days of that process of leapfrog.”

“He’s the leader. He’s the commissioner. Where was the innovation, the creativity that he’s known for?”

— A high-ranking official at a Pac-12 school on Larry Scott’s handling of the start of the 2020 season

It’s possible Scott might not be the one leading the leap. Schill would not address whether discussions have begun about an extension for Scott but credited the commissioner’s “prescience” in securing daily testing.

“Having that testing partnership in place really gave everyone the courage to make a decision that everybody wanted to be made,” a high-ranking official at a Pac-12 school said. “If you want to criticize him for anything, it’s that he got the testing partnership in place and then did nothing.”

Bryant said that Scott introduced Quidel to Big Ten commissioner Kevin Warren. Yet, it was Warren’s conference that was first to announce its fall restart Sept. 16 with the Pac-12 voting to return Sept. 24.

While the Big Ten began its season Oct. 23, the Pac-12 kicked off Nov. 7, giving its teams two fewer weeks to make their case for the College Football Playoff.

Are universities getting good returns on their coaching investments? Here’s how much every NCAA college football coach is paid in the Power Five.

“That’s where the leadership was absent,” the administrator continued. “We got this testing partnership and there was really no good reason for it because he wasn’t taking the expected subsequent action of ‘Now that we’ve got this thing, let’s play football.’ ”

“He was hanging on the coattails of the Big Ten,” another high-ranking official at a Pac-12 school said. “To be honest, I think everyone in the conference was. But he’s the leader. He’s the commissioner. Where was the innovation, the creativity that he’s known for?”

Last week, as the Pac-12 ramped up for its season-opening weekend, two of six games were canceled because of COVID-19 concerns — Washington-California and Arizona-Utah. The Pac-12’s late start left no room to make up those missed contests.

Friday, the Pac-12 issued a news release admitting that a testing error — a false positive — led to Stanford quarterback Davis Mills and three other players having to sit out its Nov. 7 loss at Oregon, and apologized to the Cardinal.

Hours later, the league followed with releases announcing the cancellation of Saturday’s Arizona State-California game and Utah-UCLA because of COVID-19 issues for the Sun Devils and Utes. In response, the Pac-12 approved a Sunday morning game between Cal and UCLA at the Rose Bowl — potentially, a nice save.

Still, despite Scott’s efforts with Quidel, the Pac-12 finds itself playing catch-up once again.

::

Larry Scott went long — so long that now the good times seem like a lifetime ago.

It was Scott who in 2010 had the then-Pac-10 on the brink of stealing Texas and Oklahoma from the Big 12, only to have the Longhorns back out at the last minute. It was Scott who recovered by adding Utah and Colorado to expand the footprint into the Rocky Mountains; who inked the most lucrative media rights package in college football history; and who started the Pac-12 Networks.

Before Scott, the Pac-12 was more of a mom-and-pop shop, based in Walnut Creek, an East Bay suburb, with a commissioner in Tom Hansen who worked to please his athletic directors and coaches. It was a simpler era when presidents and chancellors of prestigious academic institutions didn’t need to focus so much energy on athletics, but the TV revenue boom was coming, and, with Scott’s hiring in 2009, they wanted to be able to move with the times.

Scott was a whip-smart Harvard man who, after attempting a professional tennis career, had risen to chairman and chief executive of the Women’s Tennis Association. He came to the Pac-12 and surrounded himself with others from a pro sports background.

There were two entrances to the Walnut Creek facility — front and back. Staffers noticed that while Hansen always entered through the front and greeted people, Scott began coming in through the back and heading right to his office.

Soon, with the advent of the Pac-12 Networks, they all were going to be commuting into San Francisco’s South of Market district, where their neighbors were tech start-ups that fit Scott’s new brand of innovation.

“We were like, ‘We have a dude,’ ” a founding Pac-12 Networks employee said.

“I’m not going to be able to get a charter to fly a football team this October with the revenues that will come in 2024.”

— A former Pac-12 athletic director

The way Scott and his supporters tell it, the Pac-12’s deal with ESPN and Fox was so gargantuan that the presidents weren’t desperate to max out short-term revenues with the rights to their lesser football and men’s basketball games and non-revenue sports offerings. Scott sold them on starting their own network and using it as a marketing tool for the schools to showcase their Olympic sports prowess as the “Conference of Champions.” The goal was not to make gobs of money right off the bat.

“They have been profitable, but they certainly haven’t met the threshold of revenue that he was intending them to meet,” a former longtime Pac-12 executive said. “No matter what they say, that was definitely the top priority.”

Scott calls that revisionist history. Regardless of how one spins the network’s original mission, all parties agree that the failure to sign with DirecTV was a major setback.

“This idea that when everything expires in 2024 you control all your content, that works really well if you have the content that people want to buy,” a former Pac-12 executive said.

“If they could have done the model where ESPN or Fox owned a share of the Pac-12 Networks, then you have the biggest media companies in sports who are vested in it being successful. We had ESPN and Fox picking off the best football and basketball games in a league that already doesn’t have many, and the rest of the stuff that nobody wants to watch going to the Networks.”

As the centerpiece of a department facing a growing deficit, UCLA football has gorged itself on food spending that has no rival nationwide.

The Pac-12 Networks promised 850 live events a year — an astounding number — and hired an experienced and ambitious staff, fervently optimistic that someday DirecTV would give them the boost to get over the top and let their work be seen.

After years of waiting, and after seeing the Big Ten and SEC jump far ahead with their new TV deals, the goodwill Scott had built began to slowly decay. It did not help that Oregon’s budding football powerhouse wilted a couple of years after Chip Kelly left, or that USC still was reeling from NCAA sanctions and several questionable coaching hires. A chicken-or-the-egg argument was debated across the league: Did the Pac-12 Networks’ struggles sink the league’s competitiveness, or did the top programs’ undesirability sink the Networks? However one saw it, they all were going down together.

“I’m not going to be able to get a charter to fly a football team this October with the revenues that will come in 2024,” a former Pac-12 athletic director said. He later added, “Meanwhile, in the SEC, they’ve got so much money they’re building beautiful softball facilities.”

It became easy to point to the large salaries of Scott and his executives, or the $7 million a year in rent that the conference was paying to be in San Francisco, or the lavishness of Scott’s spending.

“Some of the conference leadership flew around the country in a way that was very different than the way the athletic directors traveled,” the former athletic director said.

When Scott was challenged about his salary by reporters, he would respond that he was being paid as a commissioner and the leader of a media company.

“He doesn’t see the other conference commissioners as his peers,” the former athletic director said. “He sees his peers as senior folks at Apple or Facebook or ESPN or Fox.”

Scott was losing the same battle of perception within the Pac-12 Networks too.

“We have executives that don’t watch, don’t know and aren’t involved,” a longtime Pac-12 Networks employee said. “What’s constantly asked around the office is, ‘What are these people doing?’”

But they did not fully lose hope that their fortunes would change. In March 2017, the Pac-12 sent an internal email to all staff trumpeting a major announcement in the subject line. Many opened it, believing this had to be the long-awaited agreement with DirecTV.

Employees eagerly clicked a link to a video. Scott flashed on the screen with a Las Vegas backdrop and, indeed, he had some news to share: His contract had been extended until 2022.

“In some ways, that was kind of the beginning of the end,” a former Pac-12 Networks employee said. “We don’t have DirecTV, you’re getting paid how much money, and the great news is that you got a contract extension? I’ve never seen leadership be more tone deaf.”

::

In the months after receiving his extension, Scott sought a new president for the Pac-12 Networks. He chose Mark Shuken, who formerly oversaw DirecTV’s regional sports networks.

But Shuken’s connections with the satellite provider did not lead to a distribution deal. Scott allowed Shuken to split his time between San Francisco and his home in Los Angeles, which further alienated Pac-12 Networks staff who wanted hands-on direction from the top.

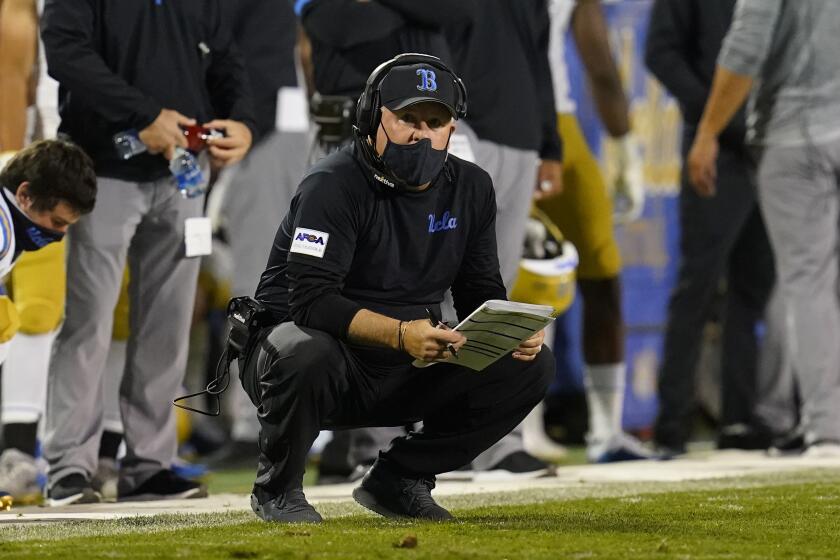

Third-year coach Chip Kelly has compiled a 7-18 record through the opening week of his third season, meaning that each win has cost UCLA roughly $1.59 million.

In January 2018, when a handful of trusted Networks executives were let go by the Pac-12, Scott’s decision to let Shuken keep his distance made more sense. Staffers called that shocking day the “red wedding,” referring to a gruesome murder scene from the HBO drama “Game of Thrones.”

A longtime Pac-12 Networks employee recalls being told those layoffs would be it. But, many months before the pandemic hit, it became clear the Networks would be scaling back their operation.

Shuken said the Pac-12 presidents approved a plan early this year to “reset the economics” and reduce “employee costs.” The pandemic gave the league some cover, but Shuken acknowledged significant layoffs were coming either way.

The schools can only hope that will mean more money in their pockets well before 2024. Pac-12 athletic directors live in fear of losing their coaches to other conferences. The most high profile of those cases came when Colorado football coach Mel Tucker spent one season in Boulder before bolting to Michigan State, which more than doubled his salary.

Shuken said he is “bullish” on the Pac-12’s positioning for the next round of media-rights negotiations.

“We know the consumer is going, so we want to make sure that we have every opportunity to talk to new platform providers as well as Fox and ESPN, and there may be a mix at that time,” Shuken said. “The world is changing faster than it ever has in the media space, and our timing seems to be just right.”

“It was shocking to witness how short-tempered and unprofessional he was, particularly when you are aware of the fact he makes over $5 million a year.”

— Andrew Cooper, one of the athletes who spoke with Larry Scott concerning the #WeAreUnited movement

In the meantime, Scott has pursued avenues to create an infusion of cash for schools. The conference entertained bringing on a private equity investor to loan a large sum in exchange for a significant stake in the upcoming media rights deal. Scott hired the Raine Group, an investment bank with experience in sports media, as an advisor to help assess the conference’s value. Raine’s research estimated the Pac-12’s total rights valuation to be worth around $5 billion, building confidence that its patience may pay off.

The pandemic has thrust unforeseen quagmires into Scott’s lap, like the #WeAreUnited player movement that launched in early August. Scott talked to 19 players on a virtual call and made it clear he was not going to engage them on the topic of players receiving any extra economic incentive to risk their long-term health.

“It was shocking to witness how short-tempered and unprofessional he was, particularly when you are aware of the fact he makes over $5 million a year,” said Andrew Cooper, a Cal cross-country runner who was on the call. “He yelled at us and told one player that he was talking out both sides of his mouth. The general sentiment amongst us was that he had absolutely no respect for the players.”

Schill, the Oregon president, said he checked into Scott’s behavior during the call and “heard conflicting stories about it.”

With Scott as a willing public shield for the presidents, what can be forgotten is that they are the ones who agreed to Scott’s salary, approve league budgets and have sent the message that they are content with his leadership.

Brothers Riley and Maddison McKibbin, who starred at USC, play on the AVP Tour and are currently featured on the latest season of “The Amazing Race.”

“The reality is, athletics is important for all of them, but they are running $3-billion organizations, and this is nothing,” a former Pac-12 executive said. “They’ve got much bigger issues than if they’re paying Larry too much money.”

League presidents will have a decision to make on Scott’s future soon enough, and it is unclear whether the commissioner remains on solid ground.

The pitch for Scott is that he set this plan in motion 12 years ago and should be the one to see it through.

“If your question is, ‘Is there anything he can do to increase the level of confidence in his ability to deliver a TV deal?’ I don’t think there’s anything he can do, no,” a high-ranking official at a Pac-12 school said. “You need to be able to win to do that, and there’s just no big win out there.”

Times reporter Thuc Nhi Nguyen contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.