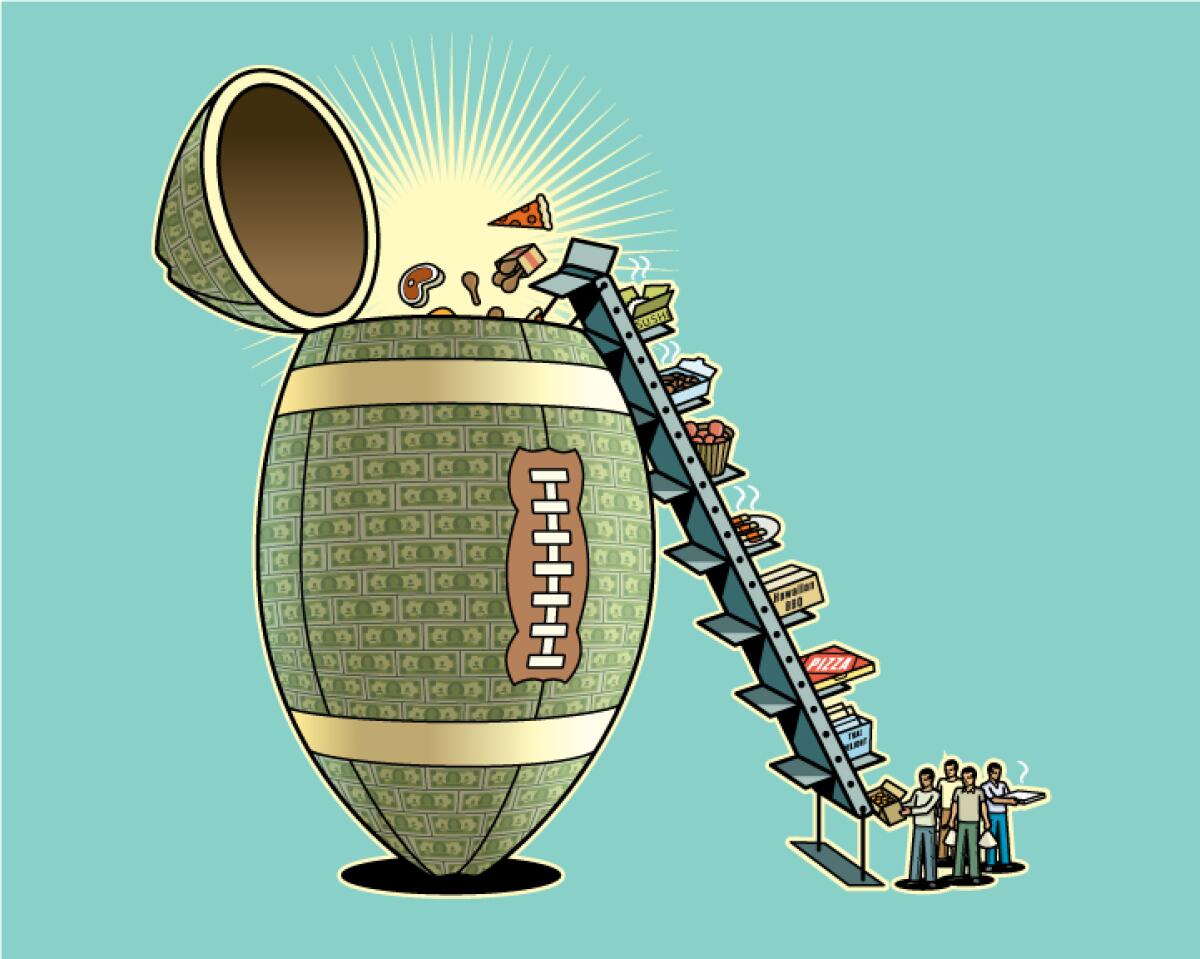

UCLA football remains success-starved, but no program is eating richer

- Share via

Breakfast was served on the terrace that summer morning in 2018, the menu featuring grass-fed flank steak, sweet potato hash with diced chicken and chocolate-chip pancakes.

This buffet on the UCLA campus befitted a faculty celebration or lavish donor event. It was neither, just the football team gathering to eat before the start of training camp.

Later, after stretching and drills, the Bruins returned to the Wasserman Football Center, where brunch selections included salmon and Cornish game hen. For dinner that evening? Grilled flat-iron steak in a balsamic reduction.

“We definitely liked the food,” former linebacker Josh Woods said.

Under coach Chip Kelly, who sees nutrition as key to the making of a football player, the fare has gotten decidedly better — and decidedly more expensive. In 2018, his first year at UCLA, the budget for non-travel meals more than doubled to $2.6 million. The following year, the tab grew to $5.4 million, dwarfing spending at higher-profile programs and raising questions about a UCLA athletic department that reported an $18.9-million deficit for last year.

Through a public records request, The Times obtained more than 500 pages of invoices and receipts that shed light on food costs. Among the menu selections: Guajillo chili chicken, coffee-braised brisket, and pork chops smothered in candied apples and onions. During off-season workouts last year, UCLA spent more than $40,000 to import five barbecue meals from an Arizona-based restaurant. On other occasions, the program ordered hundreds of peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches from a Los Angeles caterer at $4.95 each.

UCLA has not reported a positive COVID-19 test in its athletic community since Oct. 2, but it needs opponents to ward off the disease as well.

“You can obviously feed an entire football team great and nutritious food for a lot less money,” said David Ridpath, a past president of the Drake Group, which advocates for reform in college sports. “UCLA is not that great in football and does this mean a couple extra wins versus, I don’t know, spending $2 million on non-travel food?”

::

College football has long been embroiled in an arms race, with rival programs trying to outdo one another by spending tens of millions of dollars to build plush training centers and hire big-name coaches. At UCLA, it seems, this contest also includes seared sumac red snapper and organic ketchup.

When asked to comment for this story, university athletic officials responded with a written statement: “Over the past several years, UCLA Athletics has made a deliberate effort to increase our investment in our student-athletes. Among the many places of investment is the important component of nutrition, central to the overall well-being of student-athletes and allowing them to reach their full potential.”

The department cited another reason for increased costs.

The $65-million Wasserman center, which opened in 2017, includes a state-of-the-art locker room and barbershop but no dining hall. The program must pay to have food delivered and arranged on buffet tables for three, sometimes four, meals a day.

But Nick Schlereth, a researcher who has tracked athletic spending at scores of universities across the nation, suggests Kelly has been “a big part” of increased spending.

Before his arrival in Westwood, the coach was known for an obsessive approach to nutrition while running the football program at the University of Oregon and as head coach of the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles, where he famously eliminated “Taco Tuesday” and “Fast Food Friday” as part of a push for more healthful eating.

“It is a coach’s dream to control every aspect of his players’ lives,” said Schlereth, an assistant professor of recreation and sport management at Coastal Carolina University. “Food is another way they can do it.”

UCLA players say that, after the university signed Kelly to a five-year, $23.3-million contract, he asked them what needed to change.

“Me and a lot of the older guys said ‘food,’” Woods recalled. “He went out of his way and asked the administration if we could get more resources.”

Under previous coach Jim Mora, the program usually provided one meal each day, supplemented by hearty snacks such as breakfast burritos and personal pizzas. Players also could eat at student dining halls as part of their athletic scholarships.

Sam Kavarsky, the former director of performance nutrition under Mora and Kelly, said players had not been eating the right foods to maximize their potential.

“Is the women’s soccer getting the same benefits as football? What about the women’s golf team? Are they eating the same?”

— Nick Schlereth, an assistant professor of recreation and sport management at Coastal Carolina University

“There were athletes who needed to gain weight,” said Kavarsky, who left the program last year to pursue a chiropractic degree. “We were set up for failure.”

Kelly started providing breakfast, lunch and dinner for his players, using UCLA Catering & Conference Services most often. During four months starting in July 2018, for example, the program spent $2.2 million on meals. The price per head ranged from $40 to $53 a meal, according to invoices reviewed by The Times, plus occasional late-evening snacks at $29 a person. The meals were usually catered for 170 people, and the bills included $50 fees for renting umbrellas.

Players also received prepared meals to take home on weekends. One frequently used outside caterer charged $15.99 each for to-go meals, providing entrees such as free-range turkey skillet and grilled grass-fed steak, according to invoices from the summer of 2018.

Bolu Olorunfunmi, a running back from 2015 through 2018, said: “Food was never an issue when the coaching change happened.”

::

The spending might appear excessive, but it has roots in Kelly’s affinity for sports science. During his stint with the Eagles, he asked players to wear devices that tracked their sleep patterns. Hydration was regularly monitored through post-practice urine samples. At UCLA, he spoke with Kavarsky about the role nutrition played in promoting rest and performance.

The coach was focused on “body composition,” wanting his athletes to possess more fat-free mass, a higher ratio of lean muscle. The team often worked with UCLA caterers, Kavarsky said, “to source the right type of proteins, carbohydrates.”

Menus featuring ostrich burgers, wild boar and venison offered different amino acid profiles. All of this came at a cost.

Chase Artopoeus and Chase Griffin, two redshirt freshmen from Ivy League schools, are battling for UCLA’s No. 2 QB spot behind Dorian Thompson-Robinson.

“Listen, go to the market and look at the price of grass-fed beef versus ground beef,” Kavarsky said. “You have to be realistic. … You get what you pay for.”

Splurging on food coincided with other cost increases for an athletic department that was running a deficit for the first time in nearly two decades. The department had to secure an interest-bearing loan from the university to cover the gap. The next NCAA financial disclosure, covering the fiscal year through June 30, 2020, isn’t expected to become public until January. The numbers will likely be further dragged down by losses from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some of the budget strain relates to more than $16 million in severance costs incurred after firing Mora in 2017 and men’s basketball coach Steve Alford the following year. But expenses also include a significant investment in football, with the budget increasing from $27.3 million in 2017, Mora’s last full year, to $35.4 million under Kelly in 2019.

While the program plowed more money into areas such as support staff, recruiting and game expenses, spending on meals represented 15% of the team expenses and the single biggest increase in non-severance spending.

By comparison, other Pac-12 schools spent from $399,000 to $1.2 million on non-travel football meals in 2019, according to financial disclosures filed with the NCAA. That doesn’t include Stanford and USC, which don’t have to provide the information because they are private.

Powerhouses such as Ohio State ($3.4 million) and defending national champion Louisiana State ($381,000) didn’t come close to the Bruins’ total.

UCLA officials contend it is inaccurate to draw a spending comparison because many Power Five programs have athlete-specific dining halls and shift overhead and operating costs for those facilities into other parts of the budget. Further, officials said, dining halls charge a flat fee per person while caterers are more likely to charge based on consumption.

The increased spending at UCLA has not translated into success on the field so far, with the Bruins going 7-17 under Kelly. Average game attendance at the Rose Bowl has declined steadily, hitting a low of 43,849 in 2019. At the same time, ticket revenue dipped from $19.8 million in 2014 to $12.5 million last season.

“Nutrition is an important ask because it correlates to strength and conditioning,” said a former athletic department official who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But in the end, recruiting is more important. If you don’t have the players, it doesn’t matter.”

Kavarsky, who has consulted for schools across the country since leaving UCLA, insists: “Not many college football programs are putting as much emphasis on fueling their athletes.”

Sports business experts voiced additional concerns about the $5.4-million food budget in relation to spending for other UCLA teams. The school spent $6.1 million on non-travel athlete meals in 2019, with 89% going to football. Women’s basketball spent less than $97,000.

“This is insane.”

— Ramogi Huma, executive director of the National College Players Assn.

“Is the women’s soccer team getting the same benefits as football?” Schlereth asked. “What about the women’s golf team? Are they eating the same?”

::

For many years, college athletes complained about not getting enough to eat. In 2014, the NCAA finally responded by changing the rules, allowing teams to offer unlimited meals and snacks.

Under Kelly, not everything UCLA feeds its football players has been extravagant. Menus obtained by The Times include a hot dog bar with all the fixings, Buffalo chicken tenders and make-your-own sandwiches. But other invoices list London broil with roasted shallot jus; Bananas Foster French toast; ribeye steak; crustless quiche; and roasted asparagus with portobello mushrooms, feta and pomegranate seeds.

“This is insane,” said Ramogi Huma of the spiraling food budget. Huma, a UCLA linebacker from 1995 through 1998, is executive director of the reform-minded National College Players Assn.

His activism started, in part, when Bruins teammate Donnie Edwards was suspended for one game in 1995 after a sports agent allegedly dropped off a bag of groceries worth $150 at the player’s apartment.

“This type of spending is not the exception, it’s the norm when you consider runaway expenses in the form of coaches’ salaries, bloated administrative staff and luxury facilities,” Huma said. “Why not let players choose which they’d prefer since it’s supposedly all about their well-being?”

A one-year eligibility extension approved by the NCAA and a potential transfer rule could leave college football rosters in flux for a few seasons.

Other former Bruins had a different perspective; they appreciated better food. Olorunfunmi recalled that, after Kelly took over, refrigerators in the Wasserman center overflowed with snacks and sports drinks.

“I was like, ‘Whoa,’” he recalled. “They were definitely putting money into this.”

Off-season workouts represented another opportunity for appetizing spreads. Hawaiian barbecue was a favorite, with dishes like poke, Kalua pork and chicken katsu delivered by a restaurant in Carson. The price tag for one such meal approached $3,500.

“Someone would text that there was Hawaiian barbecue,” Olorunfunmi recalled. “Some guys would come just to get the food.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.