Former Clippers remember guiding influence of Elgin Baylor

- Share via

As the Clippers’ broadcaster, Ralph Lawler was paid to talk, but in the spring of 1986 he heard a piece of news that left him “dumbfounded.”

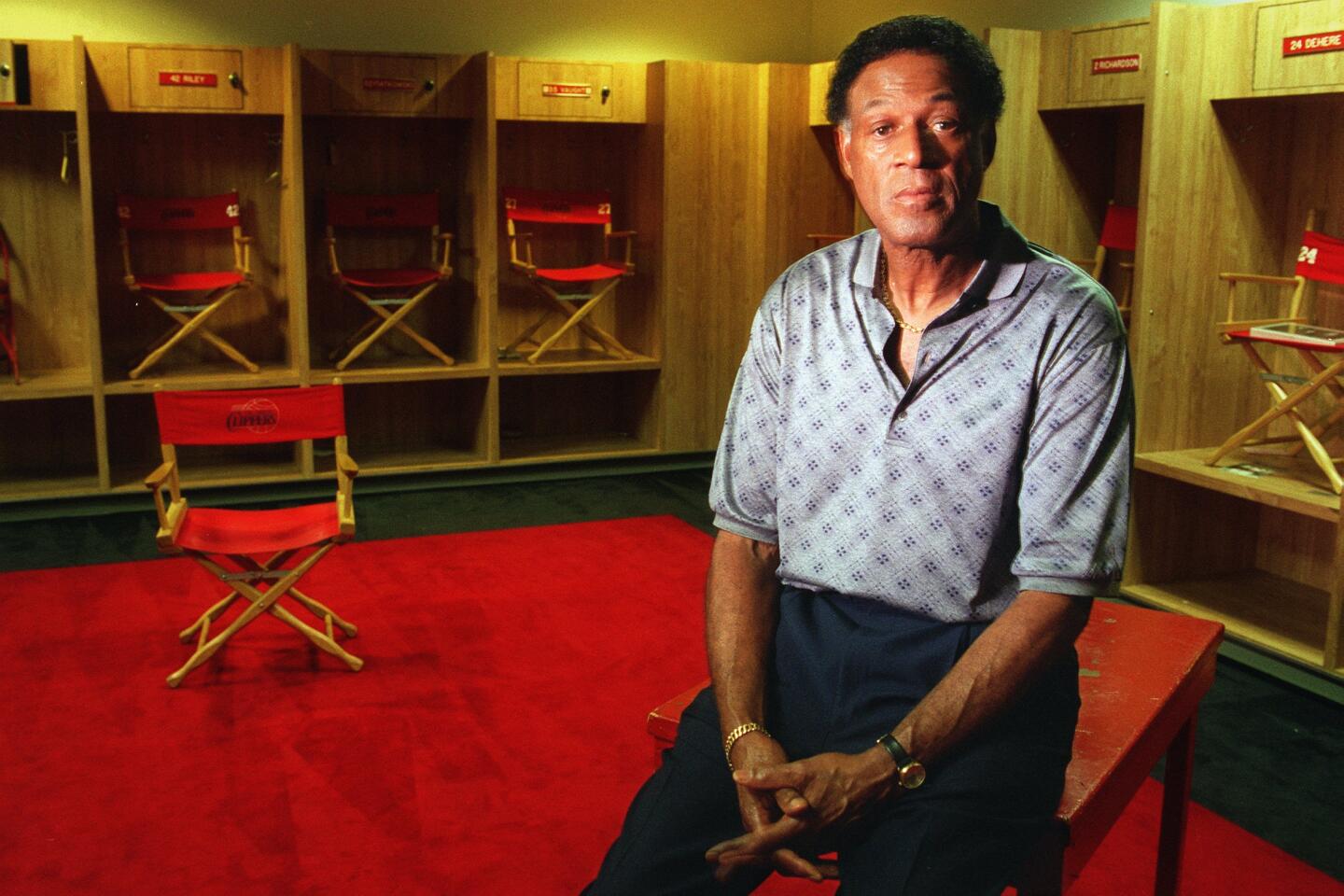

Elgin Baylor was being hired as the team’s lead basketball executive.

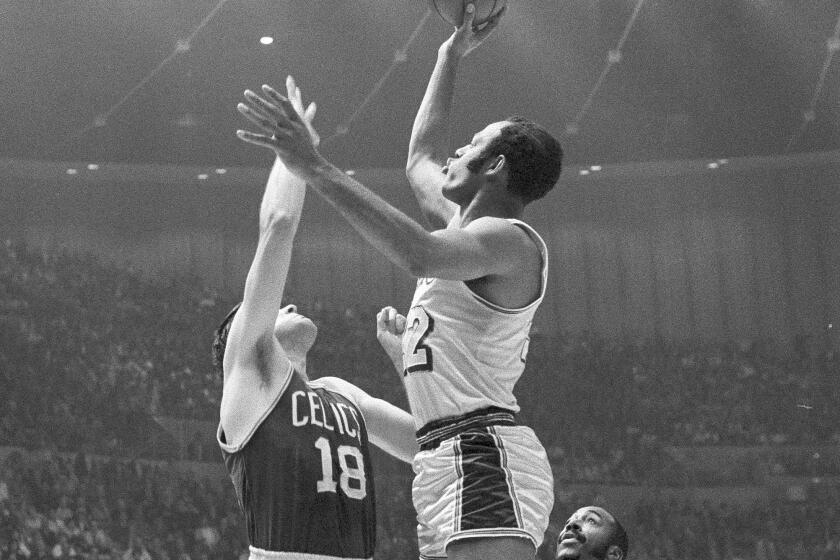

Lawler had been awed by the 6-foot-5 forward’s acrobatic game since 1957, when he saw the collegian play for the first time in Peoria, Ill. Four years later, covering Lakers training camp as a young radio broadcaster in Riverside provided Lawler the opportunity to meet Baylor, who had averaged nearly 35 points and 20 rebounds the previous season.

“He did things with the ball and with his body that nobody had done before, and it was way ahead of his time,” Lawler said.

Suddenly the broadcaster and Baylor, who had been elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1977, were coworkers. Over the next two decades, the two shared tennis courts and rounds of golf and swapped stories over late-night meals and drinks on road trips. Their wives became close friends.

Recalling Baylor on Monday, following his death at 86, Lawler paused to collect himself. The awe he felt never went away.

“He was a wonderful man,” Lawler said. “He had great moments and not such great moments as general manager, but he was a great, caring, wonderful man.

Elgin Baylor never received the level of adulation from Lakers fans that other team legends received. He was a pioneer in a town with a short memory, Bill Plaschke writes.

“I’ll miss him to my dying day.”

Baylor’s 22 seasons as the Clippers’ general manager and vice president of basketball operations marked the third and final act of his basketball life, following a brief coaching career in New Orleans. His time with the Clippers produced only four postseason appearances, three seasons with a .500 record or better, and a spotty draft record of first-round hits and fizzles before an acrimonious exit in 2008 that led Baylor to eventually sue the team, unsuccessfully, for discrimination.

Former Clippers coach Doc Rivers, who played for the franchise in 1992, said that should not overshadow his influence on the NBA, or Los Angeles, where a statue of Baylor sits outside Staples Center.

“Elgin Baylor’s name should be mentioned more with the type of player he was, the type of competitor he was, and he was a damn good dude,” Rivers said in a phone interview, adding that his time with the Clippers “made people forget who he really was, and it’s just not fair to his legacy.”

Baylor was named the NBA’s top executive in 2006 after building a roster that came within a Game 7 in the second round from advancing to the Western Conference finals, a round the franchise still has yet to reach.

“Elgin was a Hall of Famer and a legend but he was even better as a person,” said Quentin Richardson, who was drafted 18th overall in 2000 by Baylor and played four seasons with the team, in a text message. “He and Mrs. Baylor were always kind to my family and I in my entire time with the Clippers.”

The team, in a statement, called Baylor a “transcendent player, a beloved teammate and a pioneering executive” whose roles with the Lakers and Clippers made him “a Los Angeles basketball institution.”

Well into his 40s and 50s, Baylor was known to step onto the court. He once stopped a workout with big man Elton Brand to offer his tips for playing post defense.

“Back in the early days, at the old Sports Arena, the team would bring players in and Elgin would work out against them and he could outshoot all of them,” Lawler said.

“Some of those players might deny that today, but believe me, I witnessed it. He beat them all, and he loved that he could do that. People don’t realize today what a great player he was. He was extraordinary.”

One year after the team and Baylor’s 2008 split, he sued the Clippers for wrongful termination and discrimination based on age and race in 2009 for nearly $2 million. His original suit alleged that team owner Donald Sterling operated the club with a “Southern plantation-type structure”; the race accusation was withdrawn in 2011, shortly before an L.A. County jury rejected his lawsuit.

Mike Dunleavy Sr., the team’s coach who assumed player-personnel powers after Baylor’s departure, said he learned of what happened only after returning from vacation in 2008 and that his offer to persuade Baylor to return was rebuffed by top team officials.

“I don’t think he wanted to retire, and I didn’t want him to retire,” Dunleavy said by phone.

Lawler believes Baylor was rarely put in a position to succeed by Sterling’s focus on the team’s financial bottom line.

“Had he been given the free rein, a reasonable free rein, as general manager of the Clippers, I think he would have wound up being thought of as a great general manager, but the restraints of trying to operate under Donald Sterling’s guidance — those restraints, you just can’t function successfully in that kind of an environment,” Lawler said. “That unfortunately, I think, has tainted people’s vision of who Elgin Baylor was.”

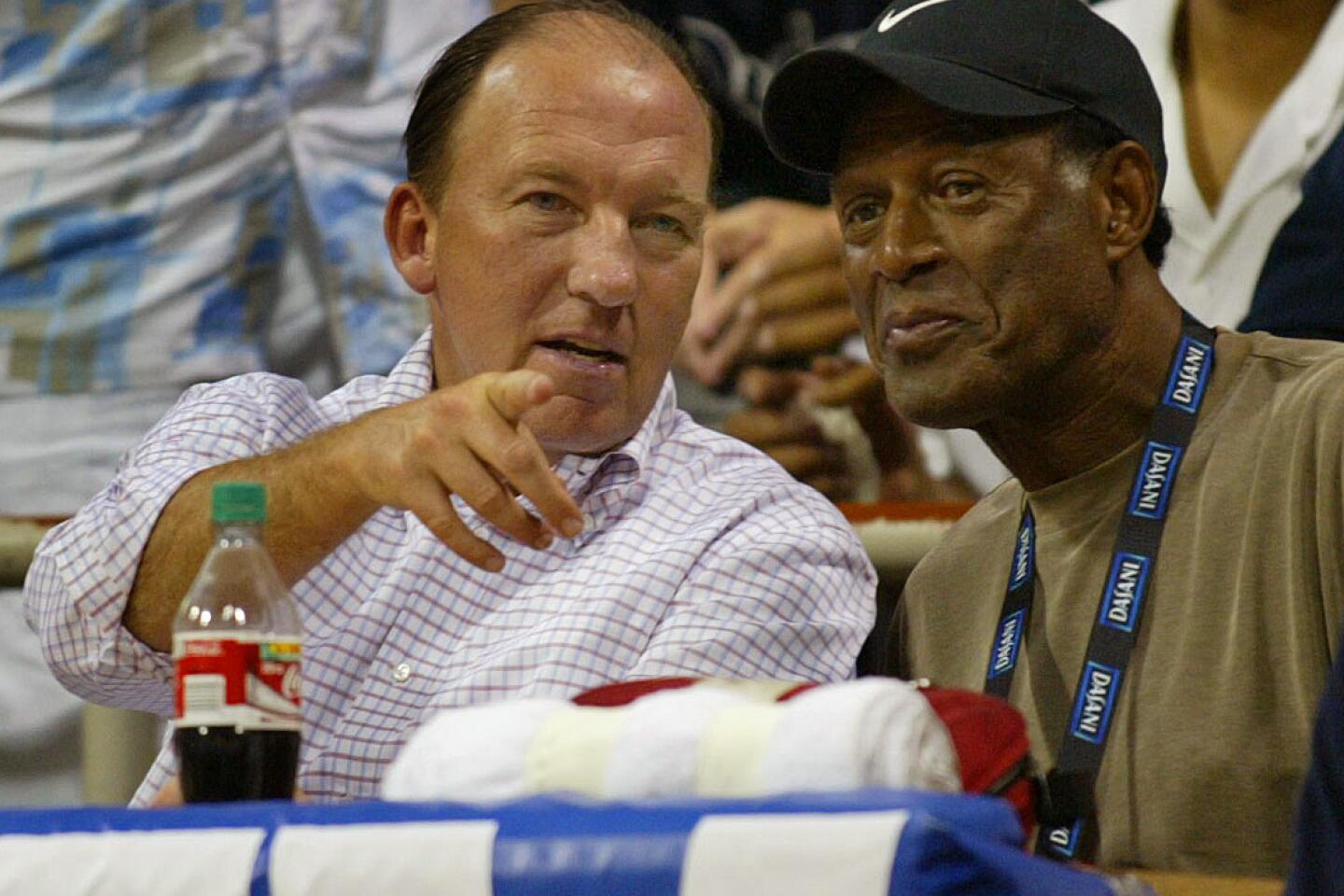

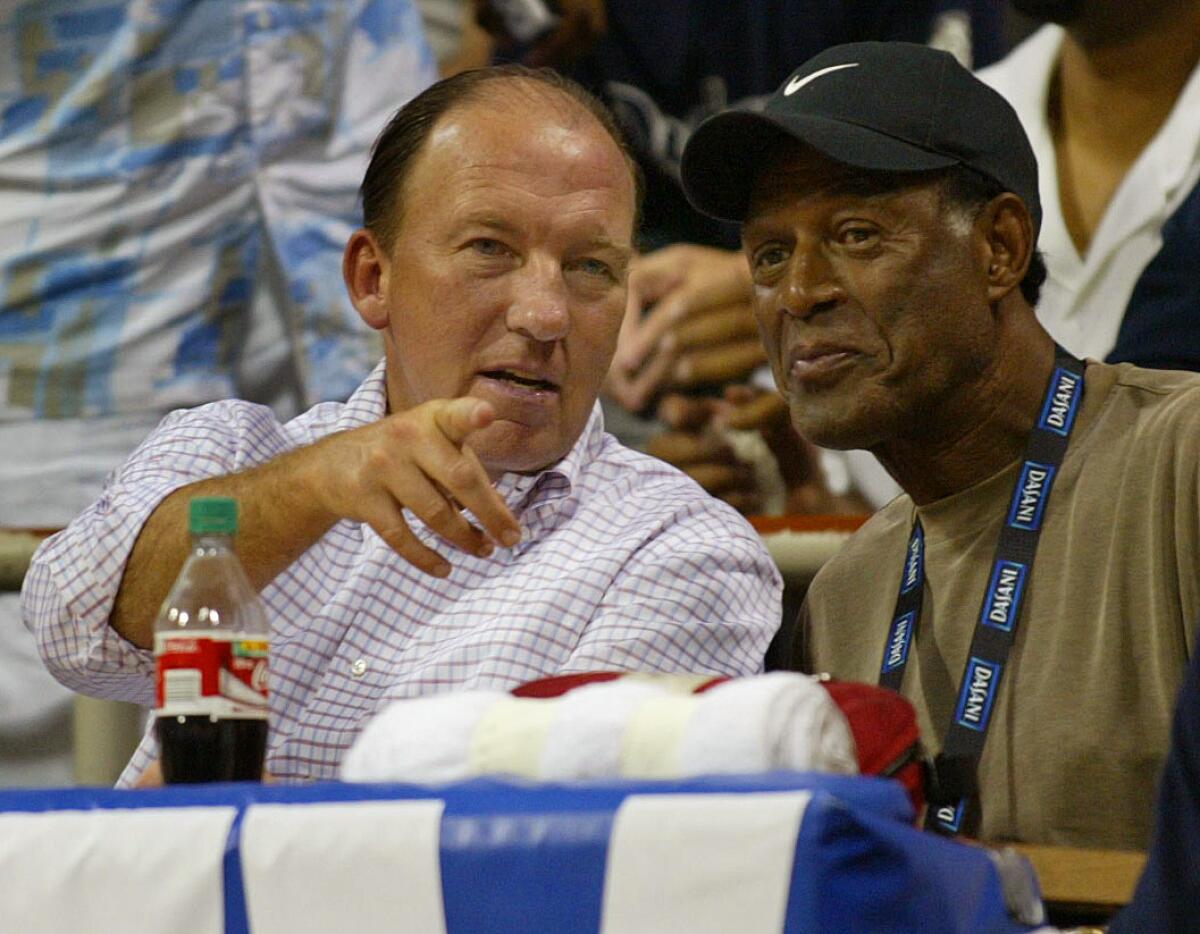

Baylor didn’t attend a Clippers game again until 2015, when he received a standing ovation and video tribute while watching a first-round playoff game against San Antonio from a courtside seat next to new owner Steve Ballmer.

“I found out that Elgin hadn’t been back, so we reached out and talked to his wife,” Rivers said. “He wanted to come back. It was great. He came back several times after that. It was just really a nice day. Really a good day.”

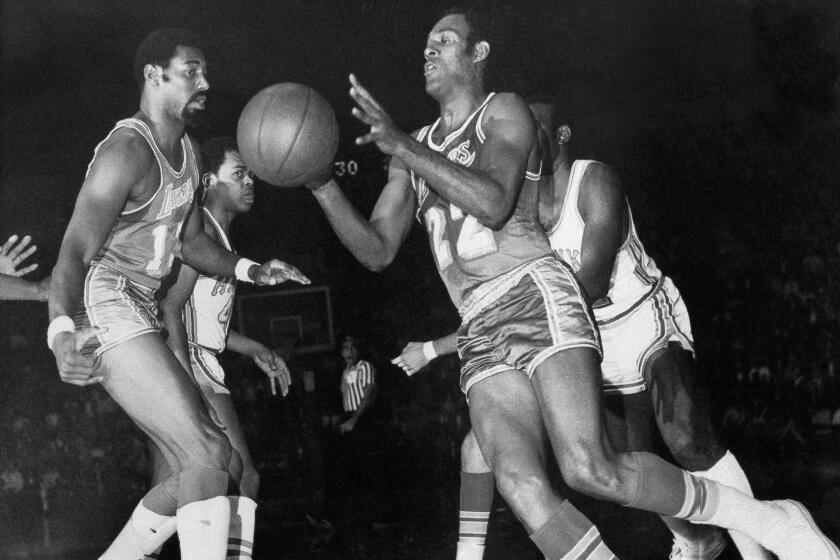

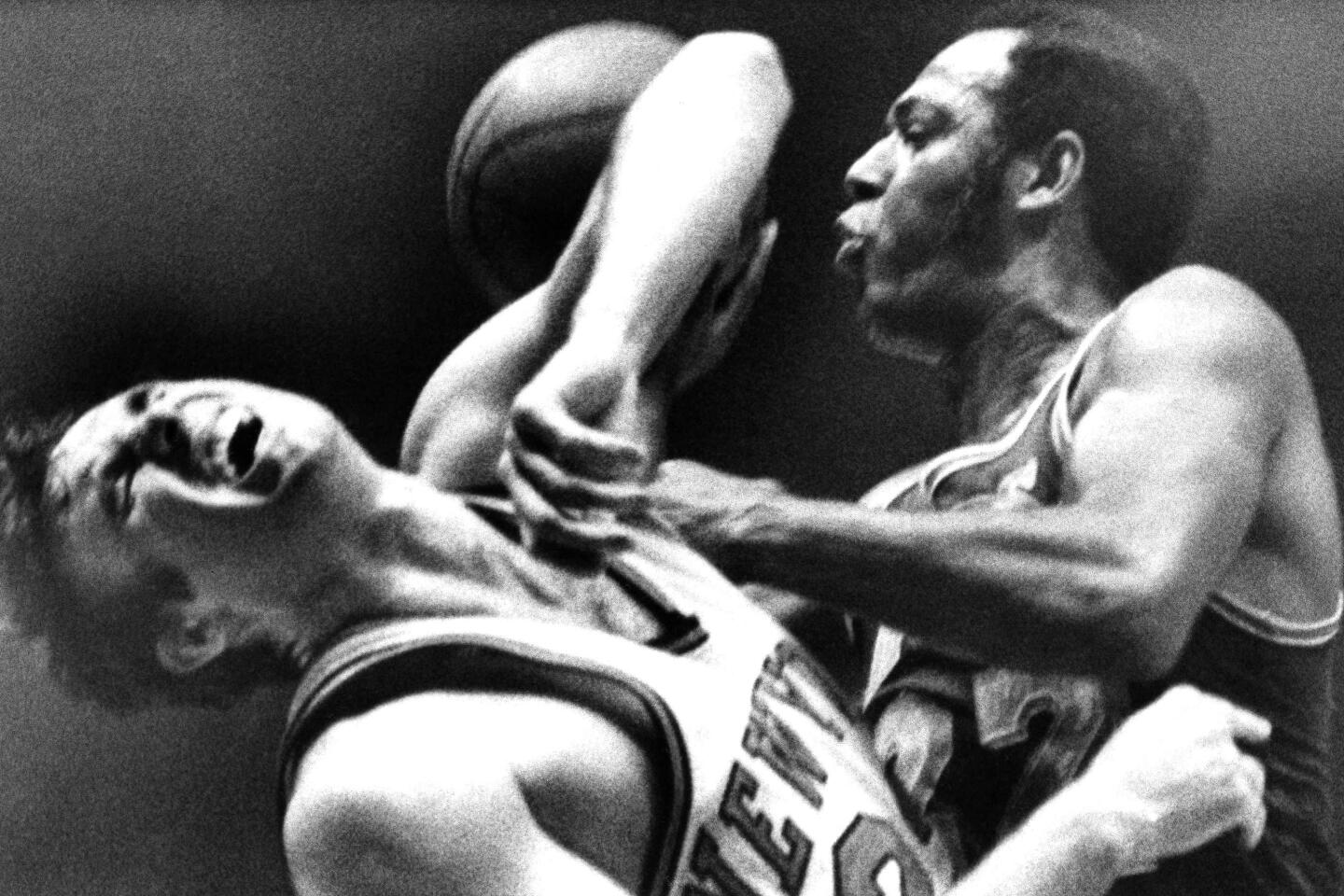

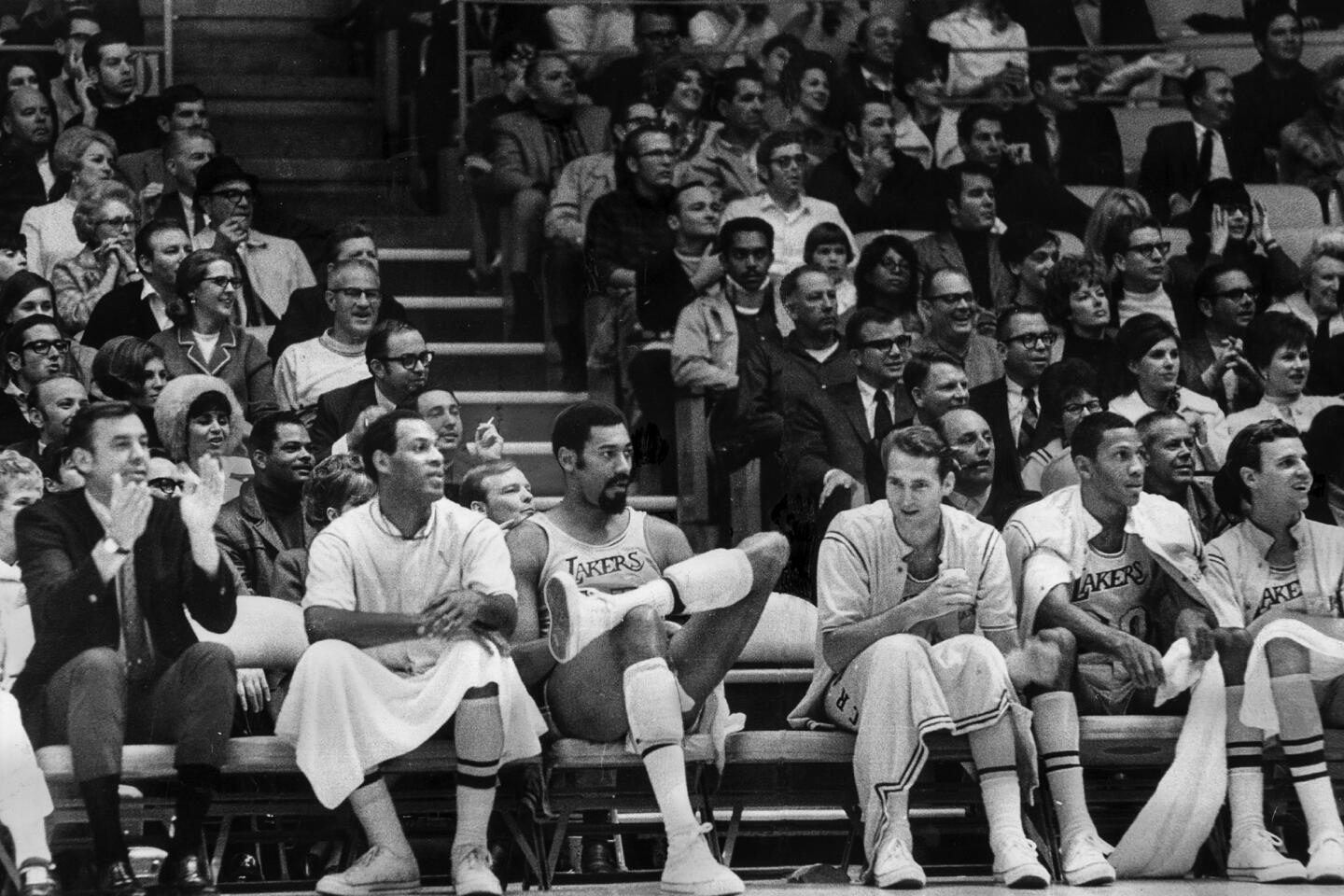

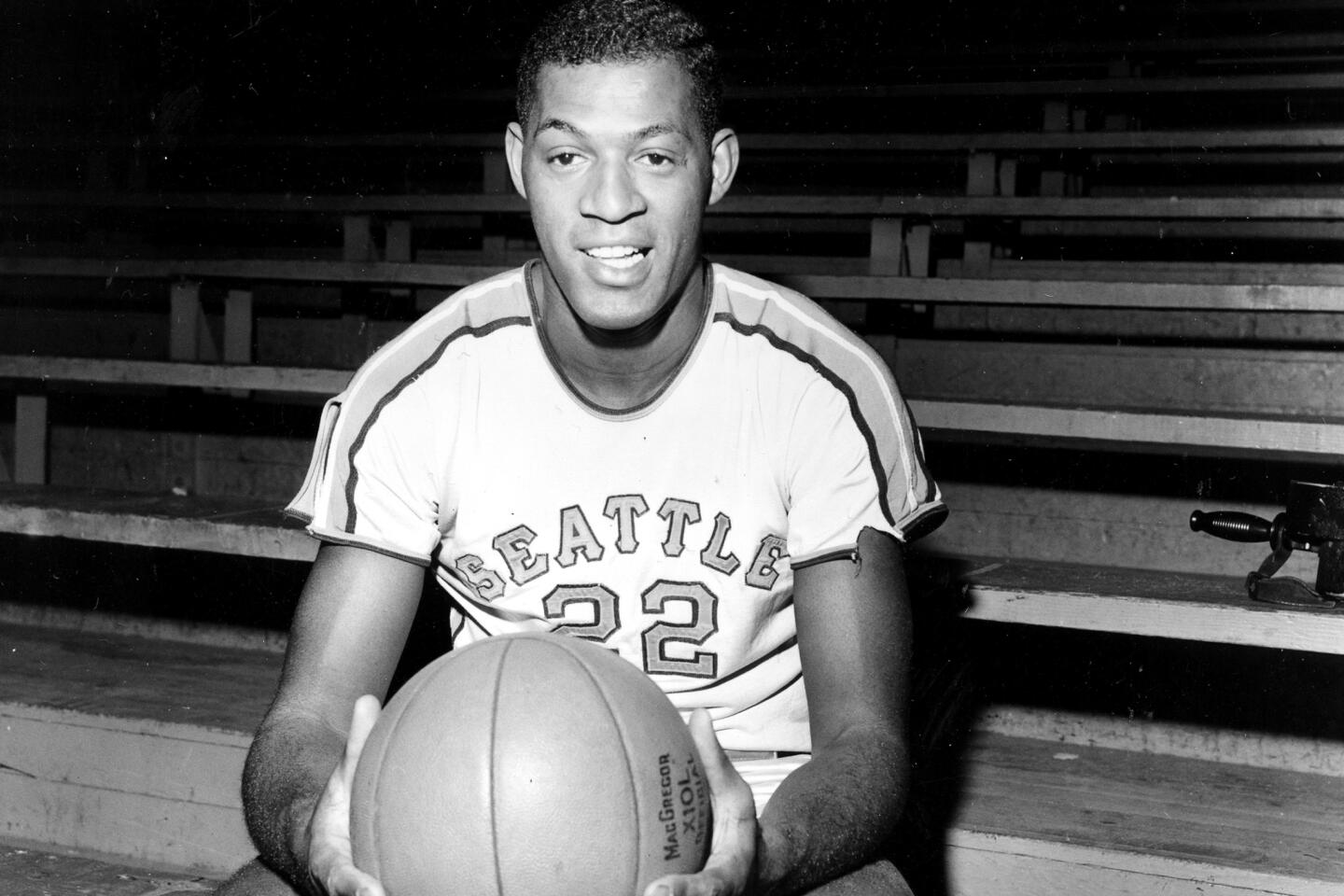

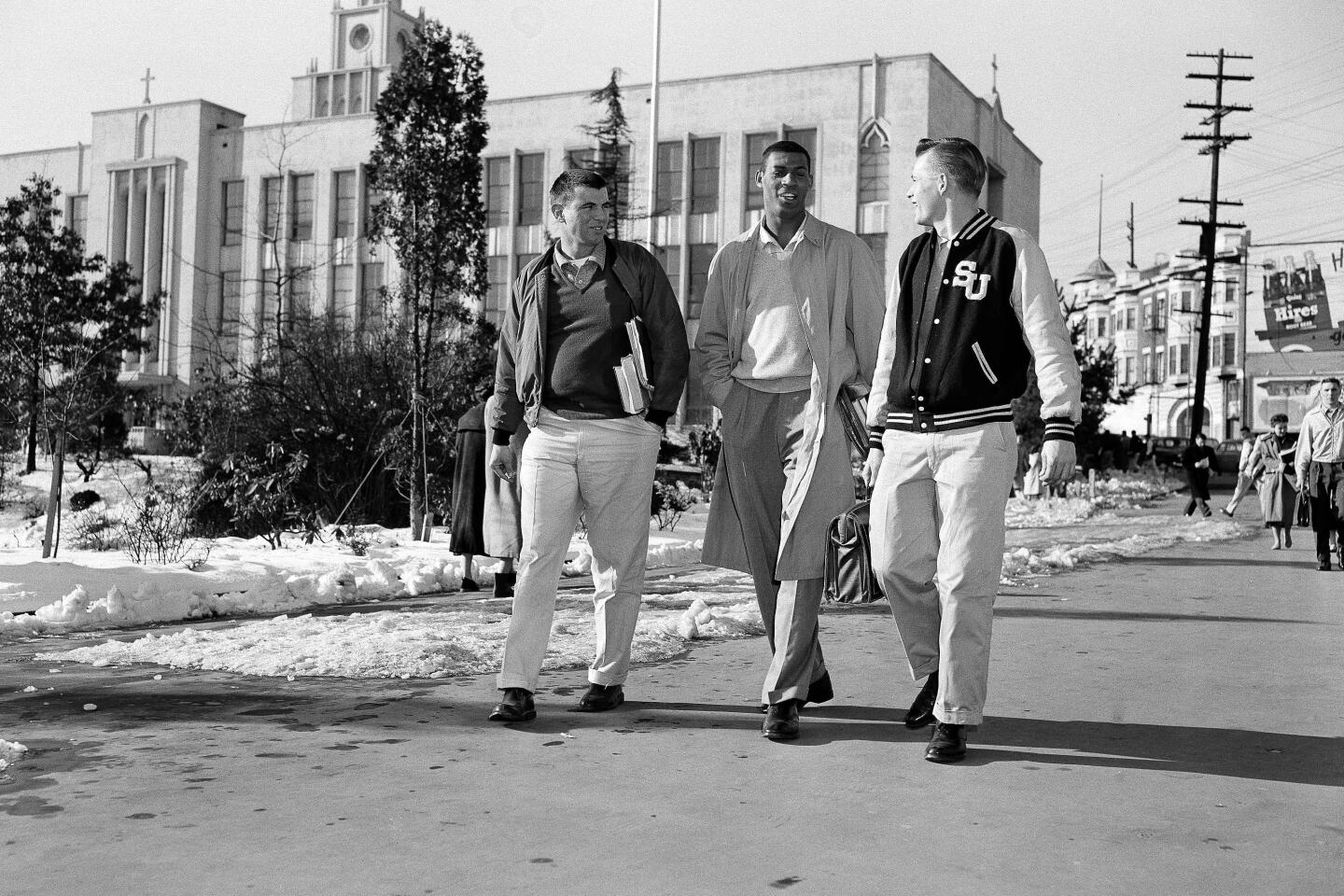

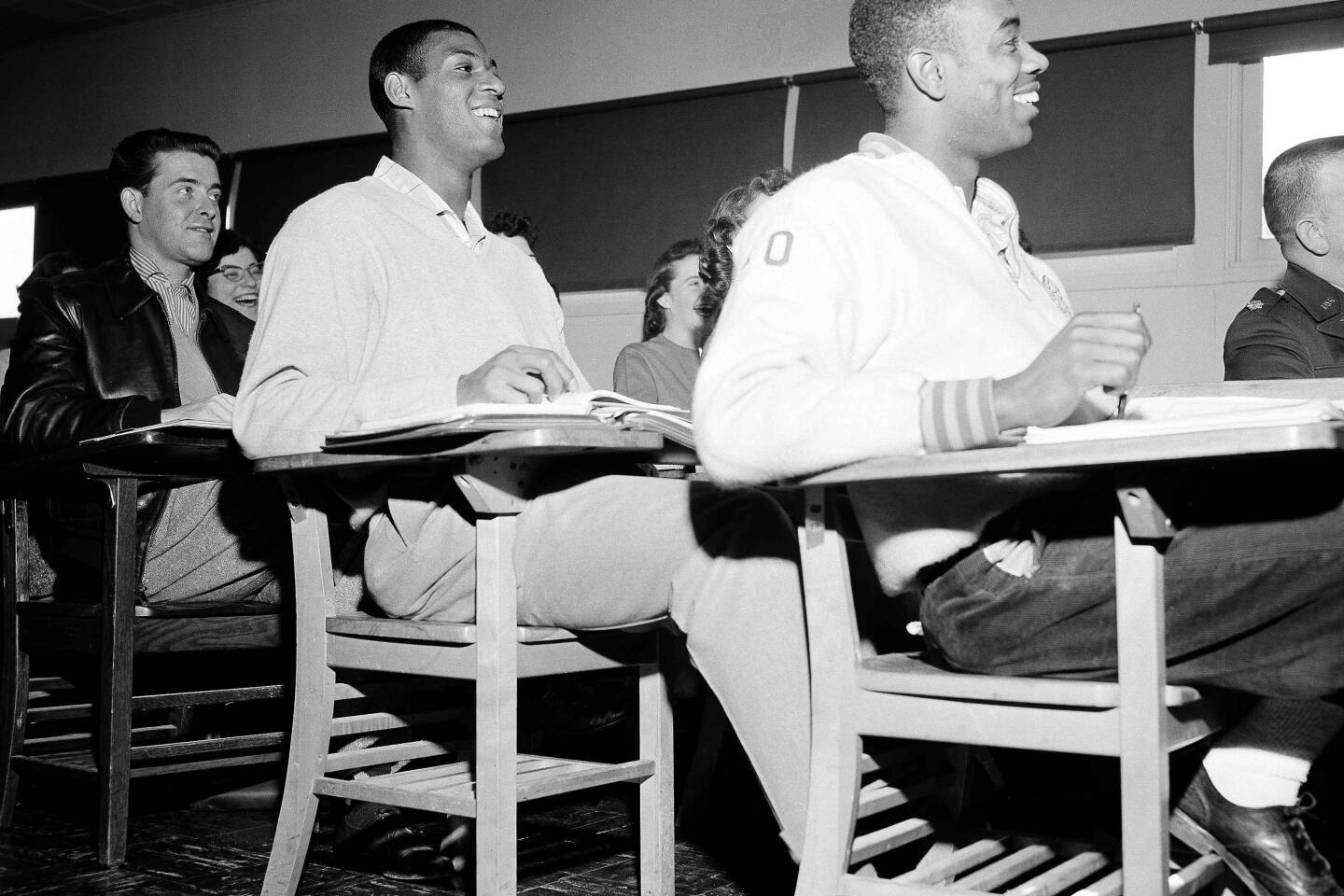

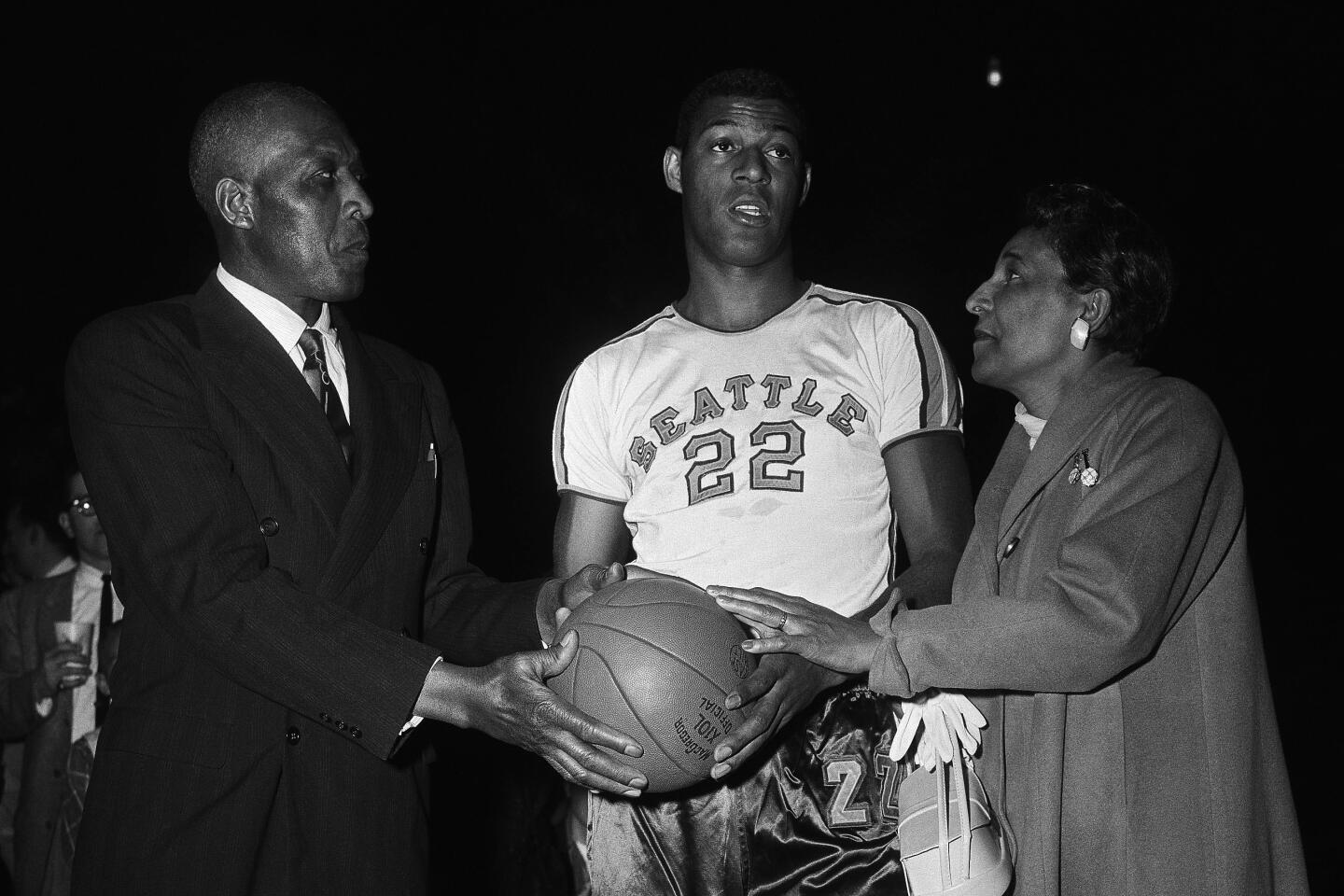

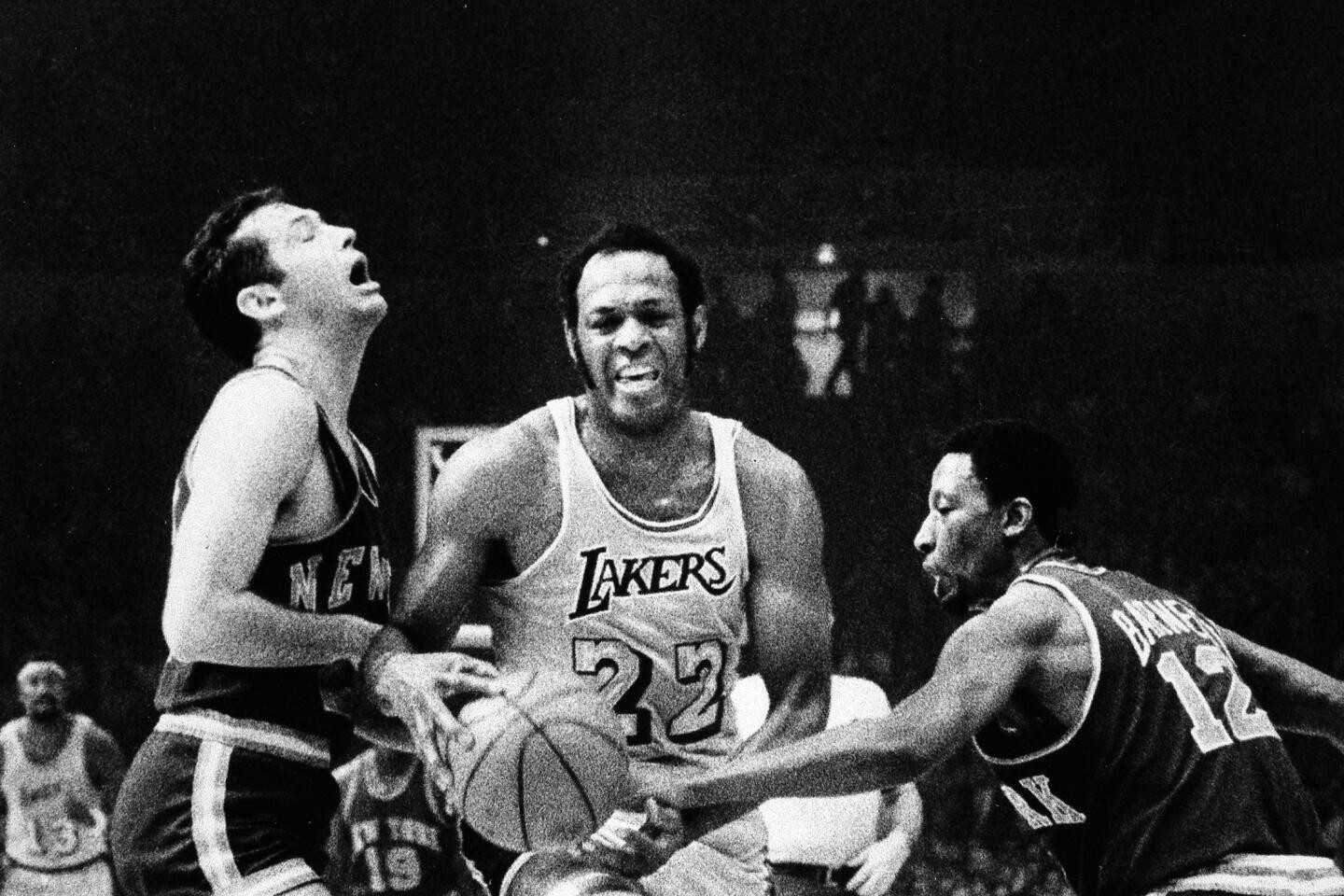

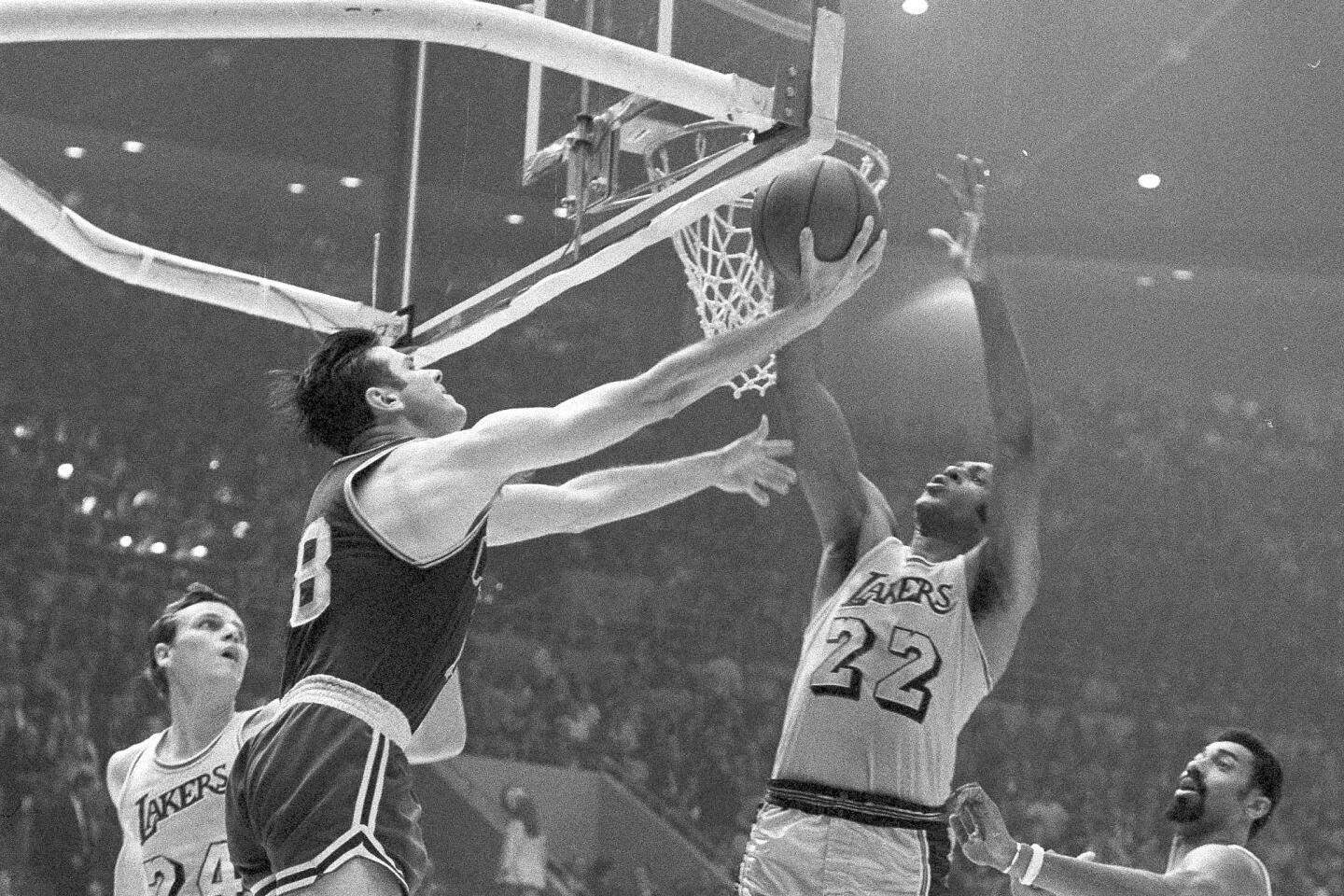

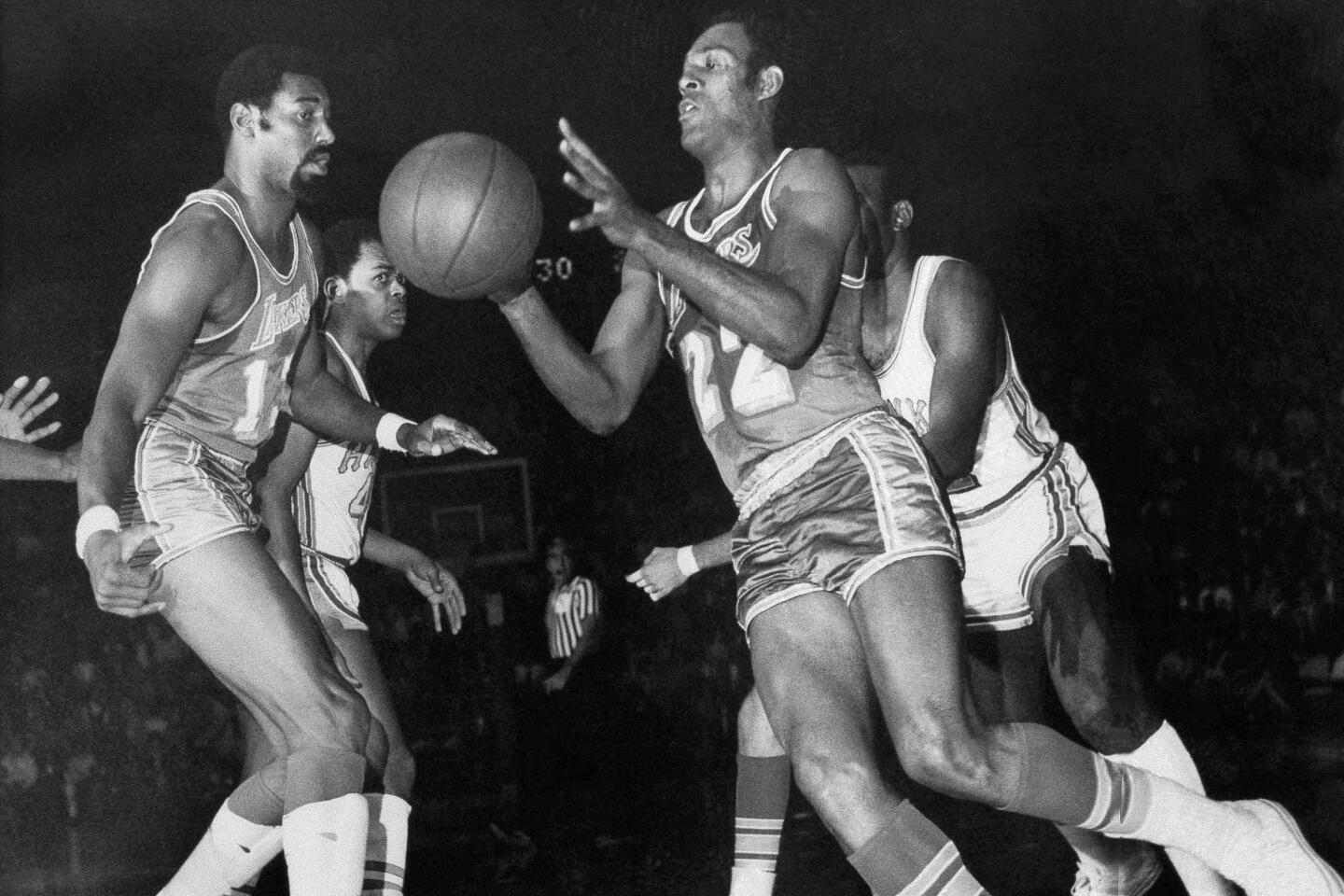

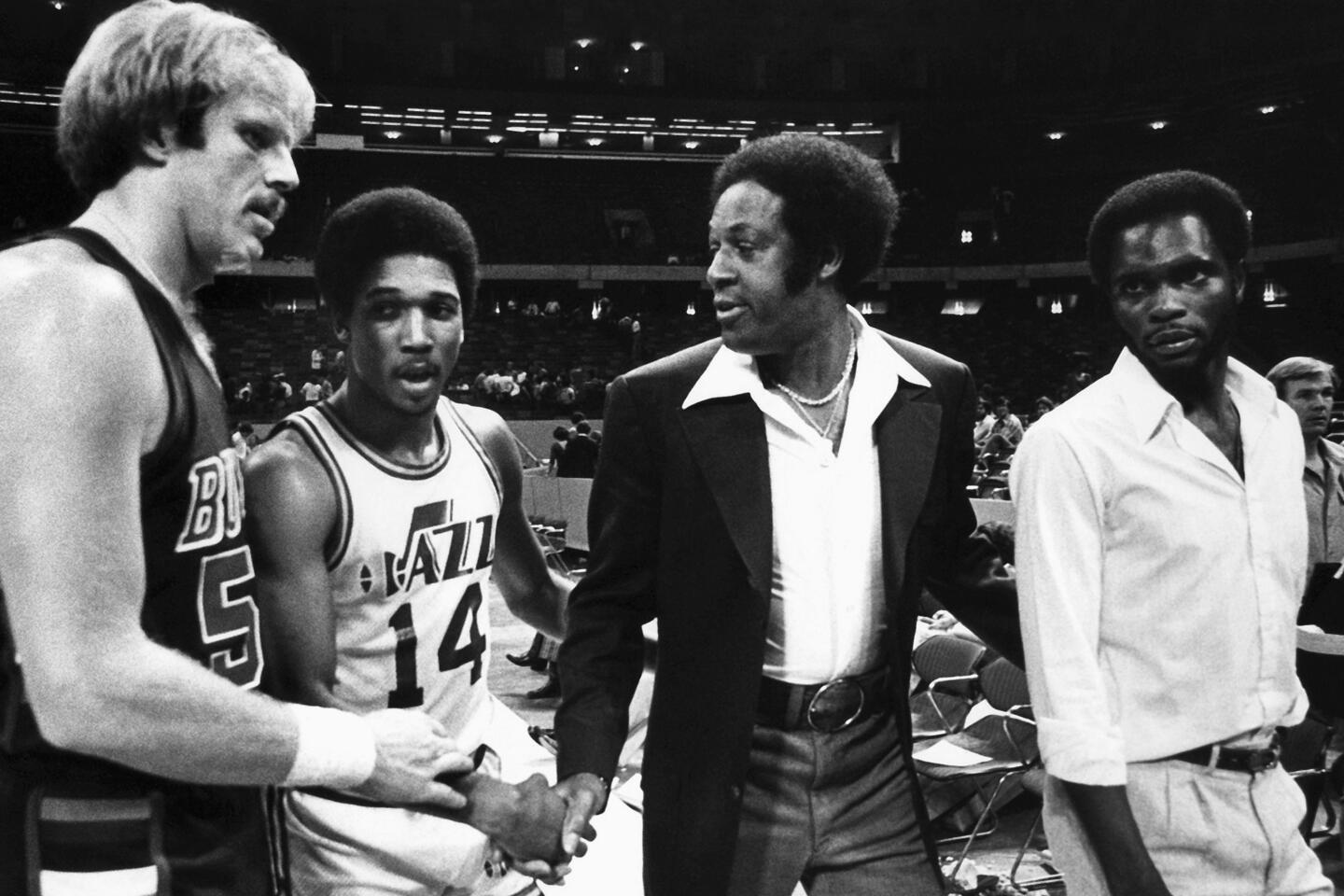

A look at the life and playing days of Lakers Hall of Famer Elgin Baylor, who would become an executive with the Clippers.

With 11 All-Star appearances and 10 first-team All-NBA honors, Baylor’s playing career drew curiosity from Clippers employees. Baylor obliged, telling what Rivers called “war stories” of an era when the NBA was hardly a mainstream draw.

He told Dunleavy about once hurting his knee but playing through the pain, only to be informed years later by a surgeon operating on the knee that he no longer had an anterior cruciate ligament. Tearing the ligament was often a career-ending jury in Baylor’s era.

“The kind of toughness, to play through something like that?” Dunleavy said.

Baylor told Lawler how after the Lakers moved from Minneapolis in 1960, he would helped drum up support by standing in the back of a truck with a bullhorn, advertising that evening’s game.

Later, Lawler said he and his wife, Jo, were stunned when Baylor and his wife, Elaine, described being regularly pulled over for no violation other than seemingly being a Black driver in an upscale neighborhood.

“He made us open our eyes to things that we were not able to see without having them as friends,” Lawler said.

Baylor “paved the way for our Black community as far as the NBA life, and the executive life of the NBA,” Clippers coach Tyronn Lue said. “I think it’s very important to understand who he was, what he meant and what he stands for.”

Lue spoke Monday with Jerry West, the Clippers’ consultant who was Baylor’s friend and teammate with the Lakers, and described him as “pretty crushed.”

West, in a statement through the team, said he “loved him like a brother” and believed Baylor’s accolades did not fully received their due. Lawler agreed.

“I think too many people today are not aware of what a great one he was as a basketball player and certainly not as a man,” he said. “He was special.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.