Column: Elgin Baylor was the first great Los Angeles Laker — and their most forgotten legend

- Share via

For years it was the saddest sound in Los Angeles sports, the public greeting of the retired Elgin Baylor at a Lakers home game.

Silence.

The ovation given other Lakers legends was absent. The affection showered upon all former Lakers was missing. Nobody stood. Nobody cheered. Nobody loved.

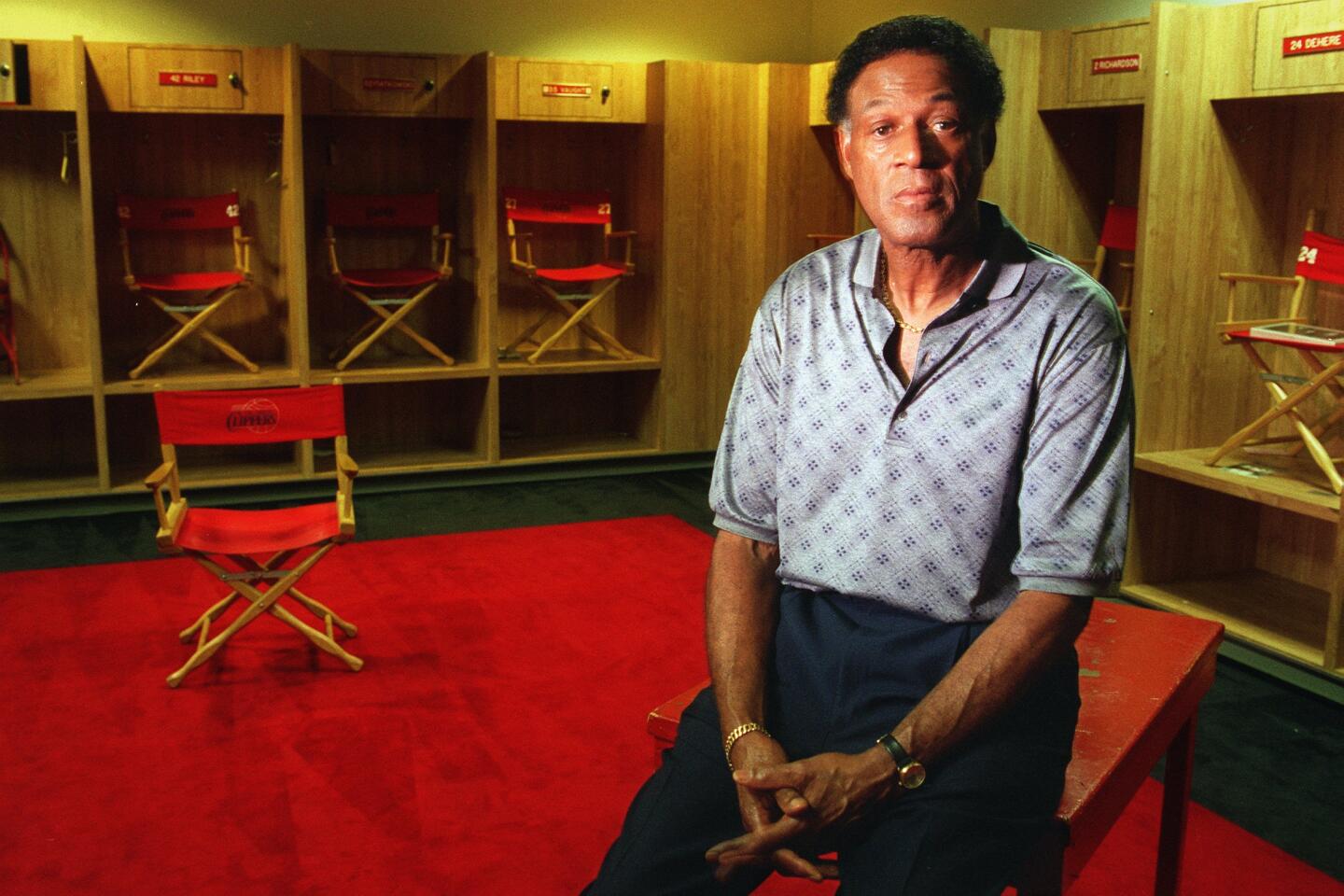

For 22 years, this cold shoulder was mostly because Baylor was a Clippers executive. Then, after Baylor finally left wretched owner Donald Sterling, the Lakers fans just never seemed to notice him.

The first great Los Angeles Laker was the most forgotten Laker.

Baylor, who died Monday at age 86, deserved better.

“I’ve always said he was one of those players who never got enough credit,” Jerry West told The Times’ Broderick Turner. “He never really talked about it.”

Elgin Baylor, the Los Angeles Lakers’ first superstar and one of the greatest players in NBA history, died Monday, the Lakers announced. He was 86.

The quiet Baylor truly never complained; he was a kind and gentle soul who never wanted to call attention to himself. But as the Lakers and the NBA meteorically soared from a winter distraction into a worldwide brand, his was a legacy lost.

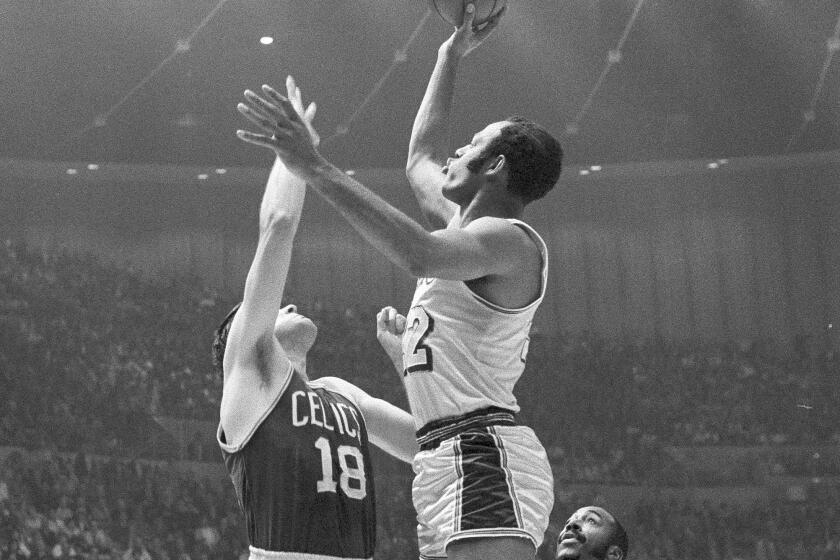

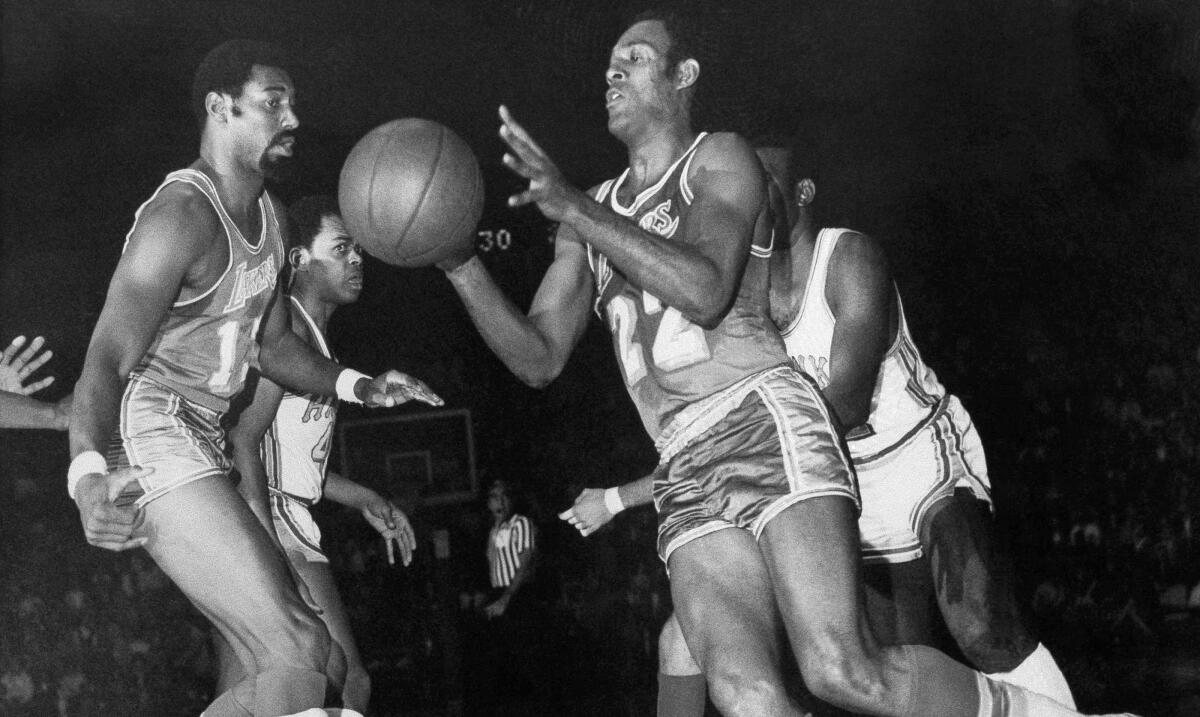

He was a pioneering Laker in a town with short memories. He was a champion Laker who never won a championship. He was the flashiest of athletes in an era from which there is scant video evidence of his greatness. He was a social justice fighter who never got his day in court.

He would outjump you, outplay you, outsmart you, but he never allowed himself to outshine you. He was always just Elgin.

“You get him one on one, talk to him, and he would tell you point blank — ‘There was nobody better than me when I was playing out there,’” Marques Johnson told The Times’ Dan Woike. “But publicly, he wasn’t the guy to get out there and toot his own horn … always playing second fiddle, no matter how great you are.”

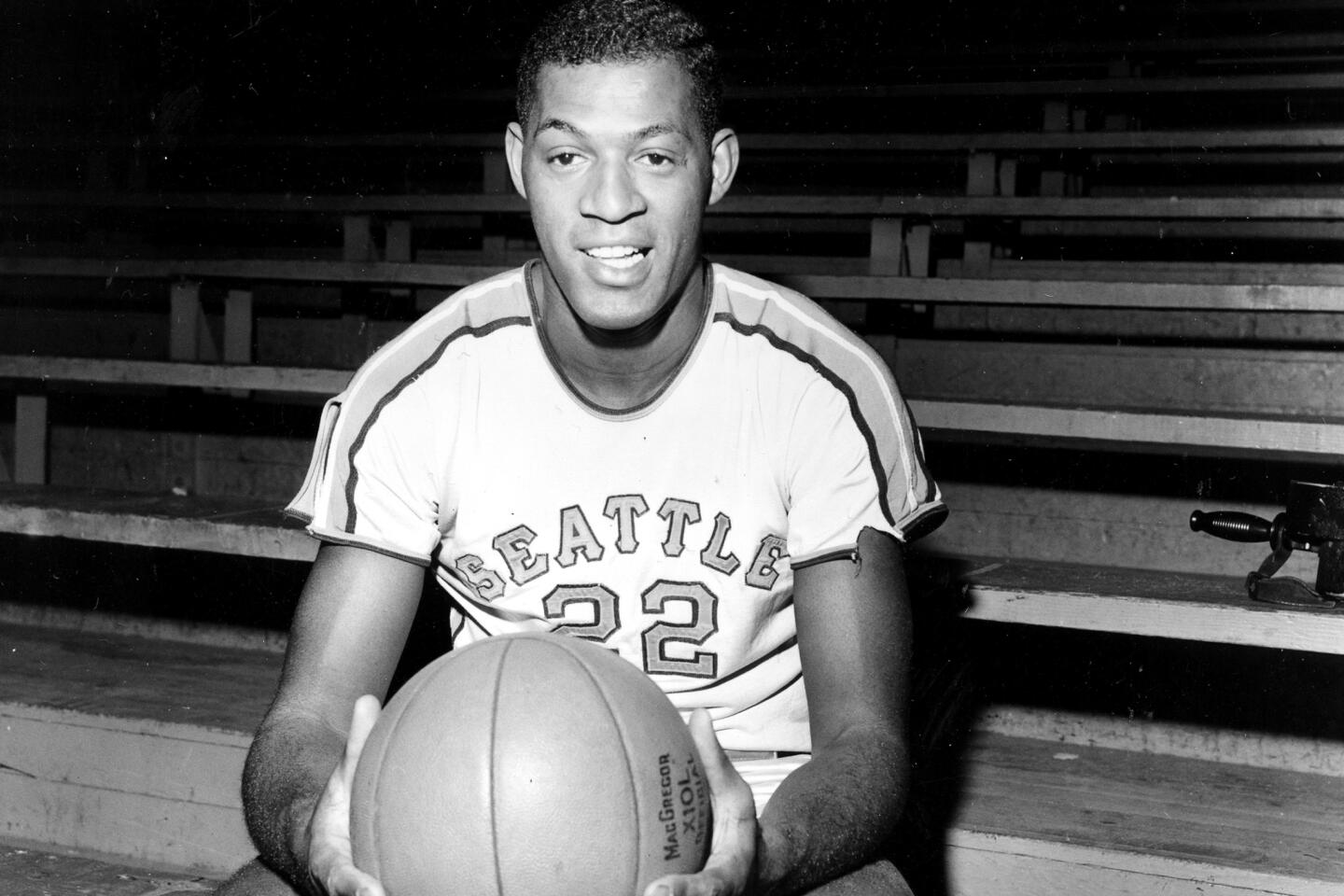

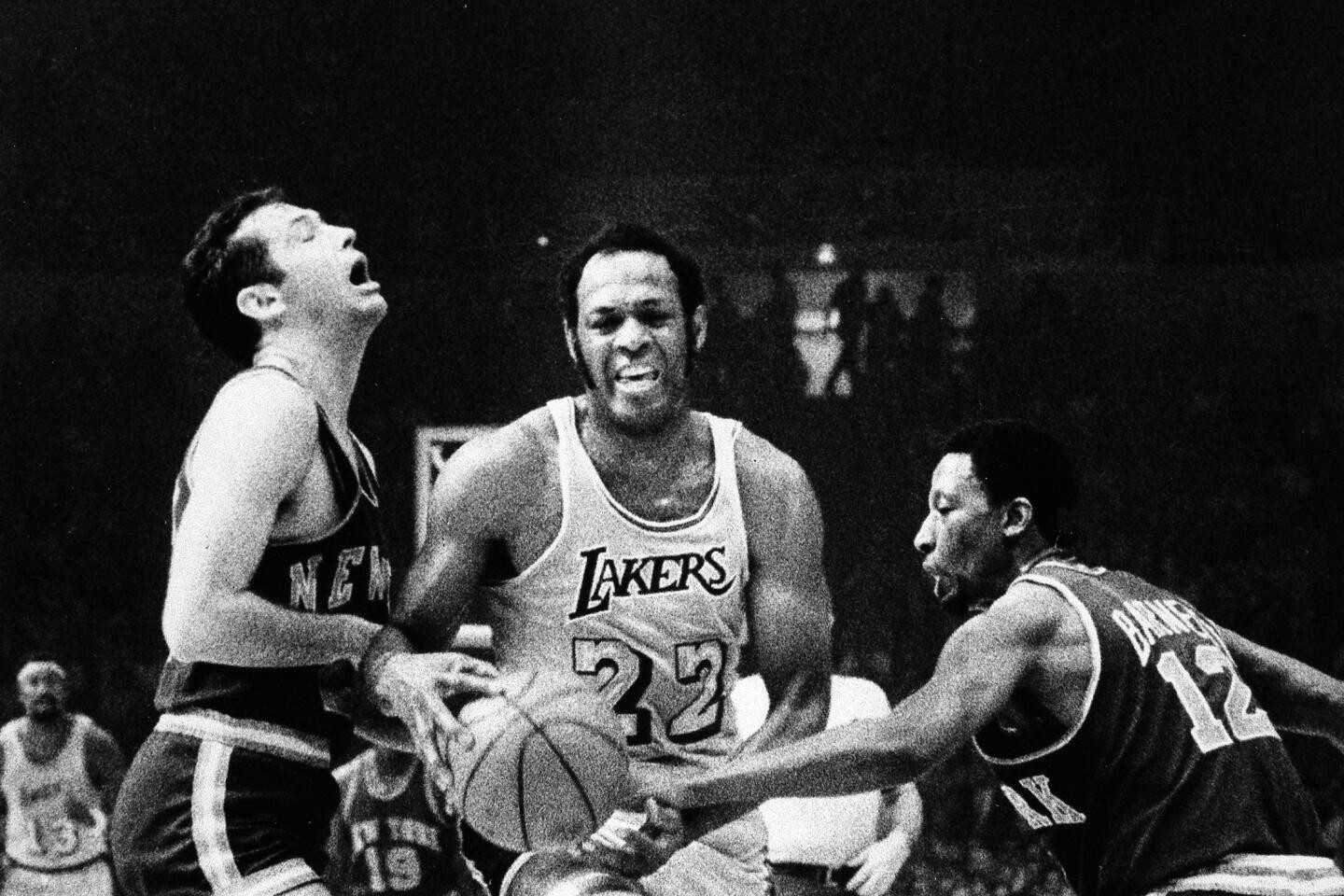

Baylor was the Laker who bridged the gap between Minneapolis and Los Angeles … yet he was overshadowed in that era by West. He played in seven NBA Finals without winning a title, then knee problems forced him to retire nine games into Los Angeles’ first championship season in 1971-72 … with the team embarking on its historic winning streak the very next game.

“When he retired, we won 33 straight games. I wonder what he felt like,” West said by phone. “With me, I would have probably felt like, ‘Oh, my God, how can I be just this incredible player and without me, we win 33 straight games and win a championship?’ I could never bring myself to ask him that. Never.”

In his best scoring season in 1961-62, Baylor averaged 38.3 points a game … yet he missed nearly half the games because he was serving in the Army. He still holds one of the NBA’s most revered scoring records with 61 points in an NBA Finals game … yet his shooting aura has long since been eclipsed by Kobe Bryant.

“I really believe he was the first Showtime,” Magic Johnson told Turner. “He was Showtime before Showtime.”

Baylor was the first person to call out Sterling for the sort of racism that eventually led the owner to be banned from the league … yet his lawsuit ultimately was dismissed. Baylor was honored with a statue outside Staples Center … but only after the Lakers had given statues to Johnson, West, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Shaquille O’Neal and Chick Hearn.

“You did some things that Dr. J, Michael Jordan, Kobe, myself, we couldn’t do,” Johnson told Baylor during the emotional unveiling ceremony.

Beginning in 1986, Baylor did something that none of today’s athletes would have to do. For 22 years he ran the Clippers for Sterling because, at the time, it was one of the few sports management opportunities for people of color.

“He didn’t have many options,” his attorney, Carl Douglas, said at the time. “He didn’t want to move, so he stuck around and hoped that things would improve.”

Back then, Lakers fans lambasted Baylor as being a traitor and a fool, but I remember a different Elgin Baylor, one who would stand tall outside the chaotic Clippers locker room in the Staples Center hallway and tighten his jaw.

“You don’t understand,” he would say. “This is something I have to do.”

After he was forced out in 2008, Baylor’s pain came pouring out when he filed a racial and age discrimination lawsuit against Sterling. He accused Sterling of saying he wanted to fill the team with “poor Black boys from the south and a white head coach.” He charged that Sterling once said of Danny Manning, “I’m offering a lot of money for a poor Black kid.”

At the time of the suit, I publicly wondered why Baylor would have remained in such an oppressive environment for so long. In reflecting back on his comments at the time, I have since come to understand. He chose to fight injustice quietly and steadily, from the inside, acting as a daily example of strength.

“I don’t think I ever heard anyone say a disparaging word about him,” West said. “He was just good. He was just good. I don’t think there was a mean bone in his body, I really don’t.”

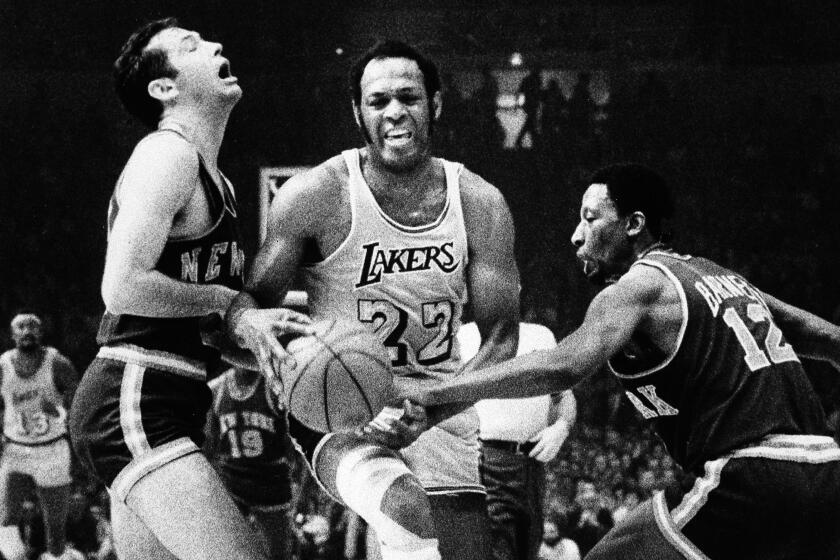

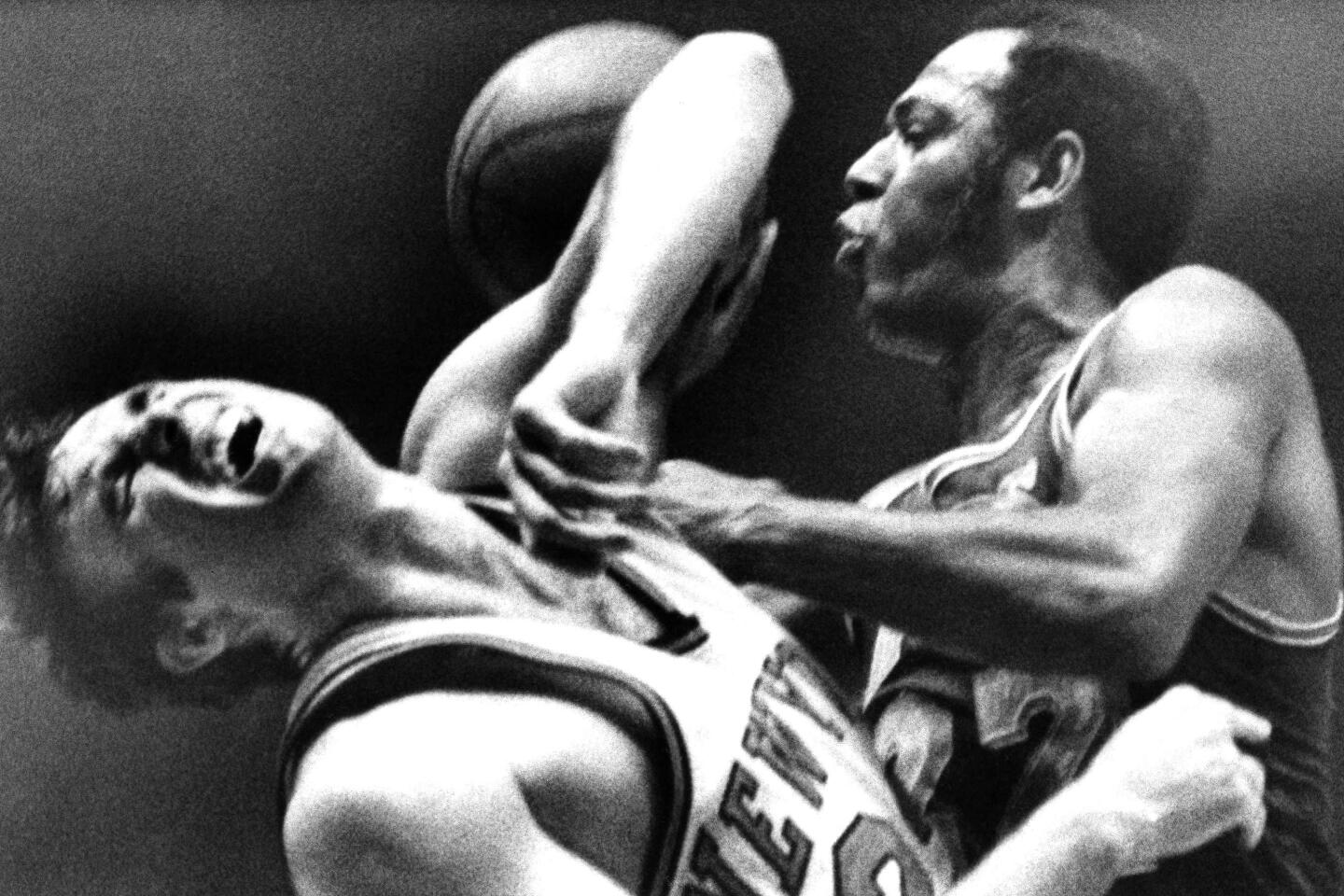

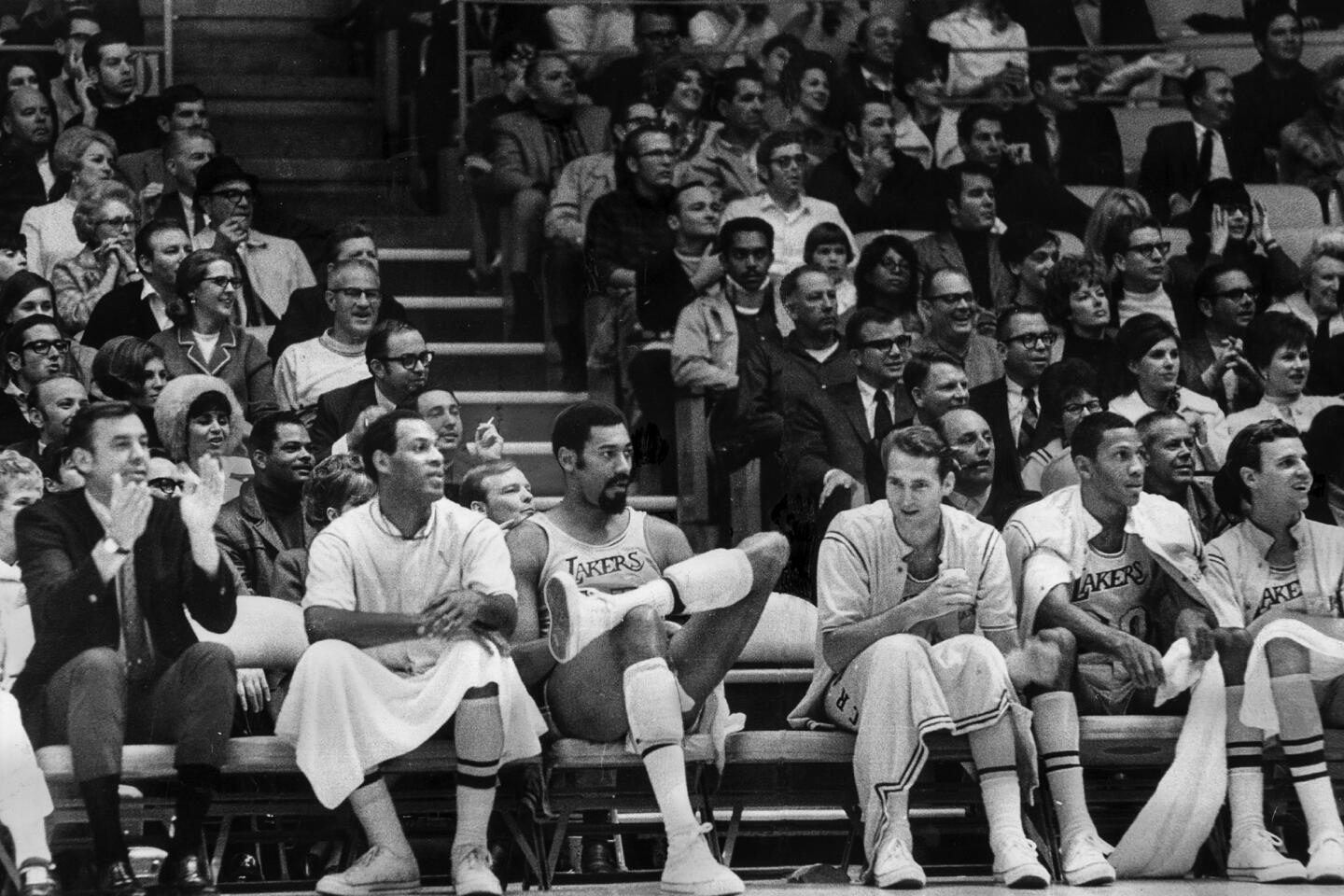

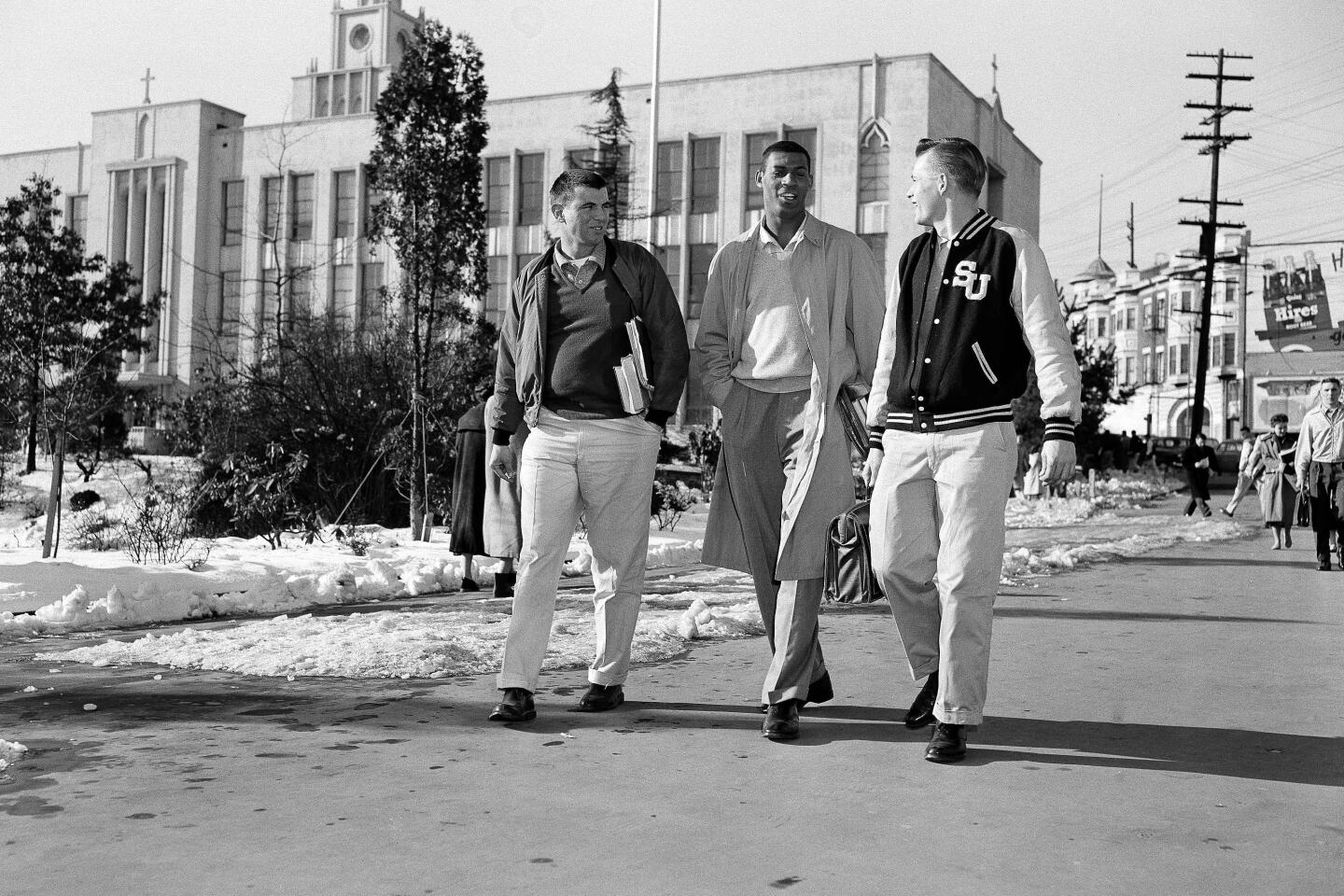

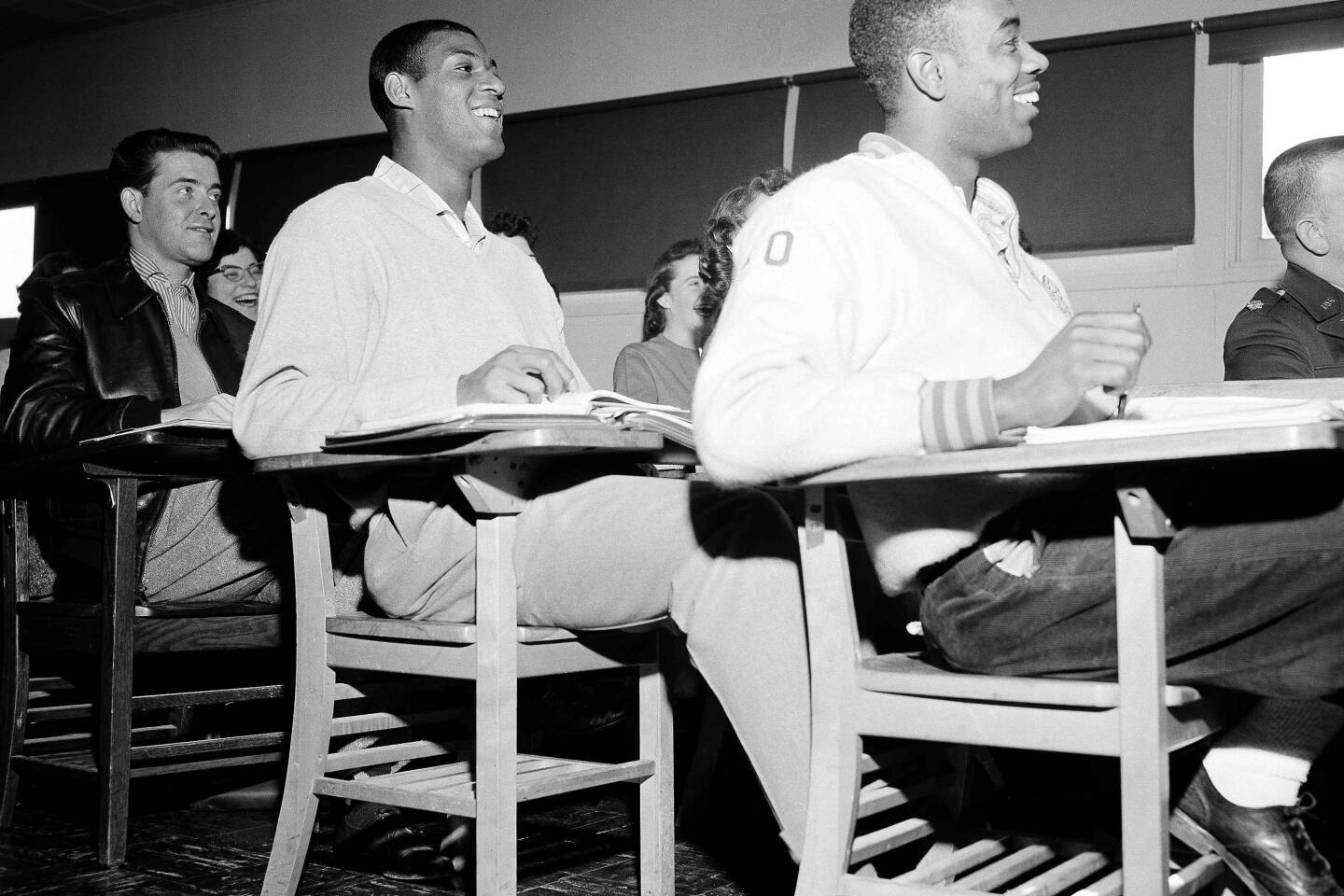

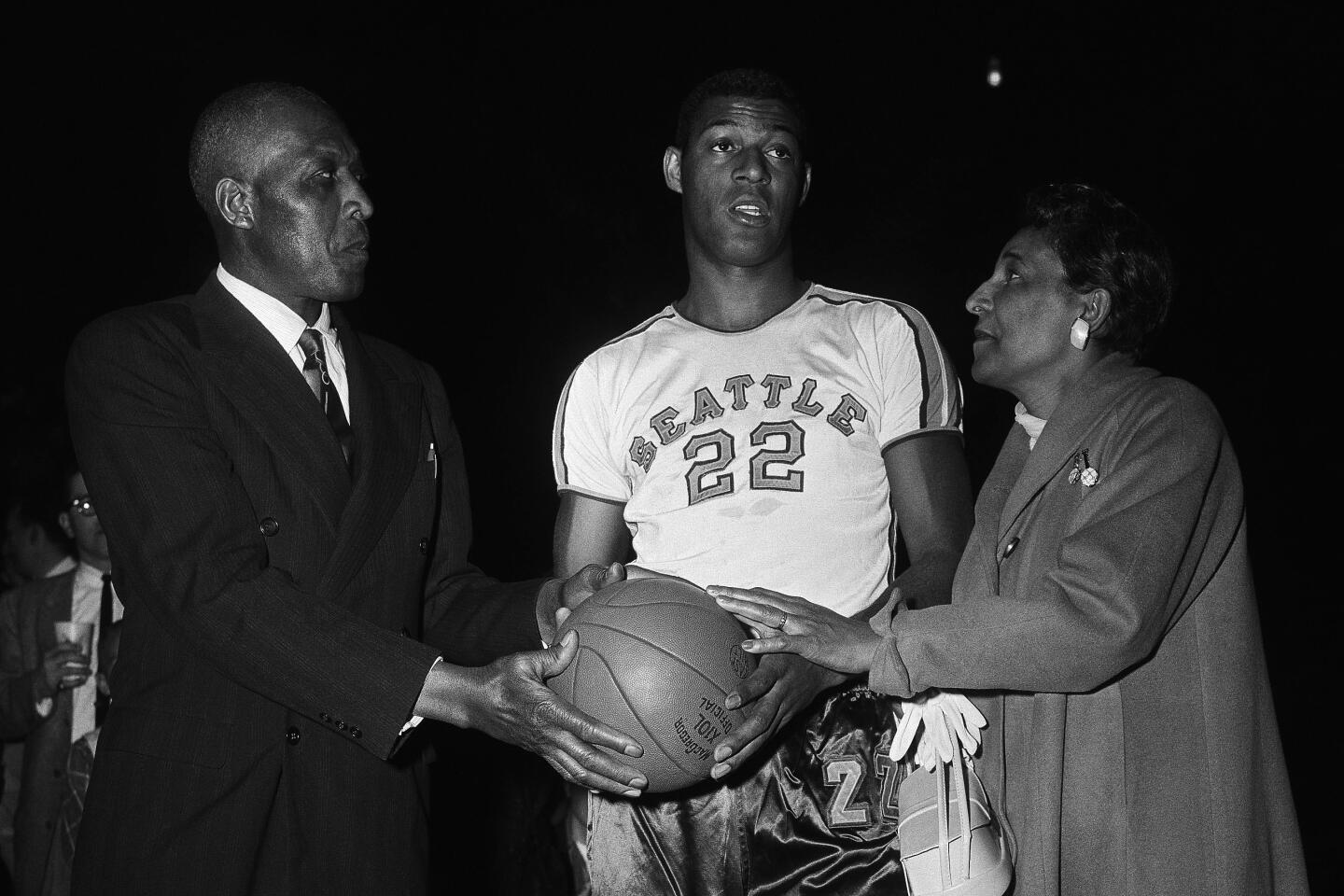

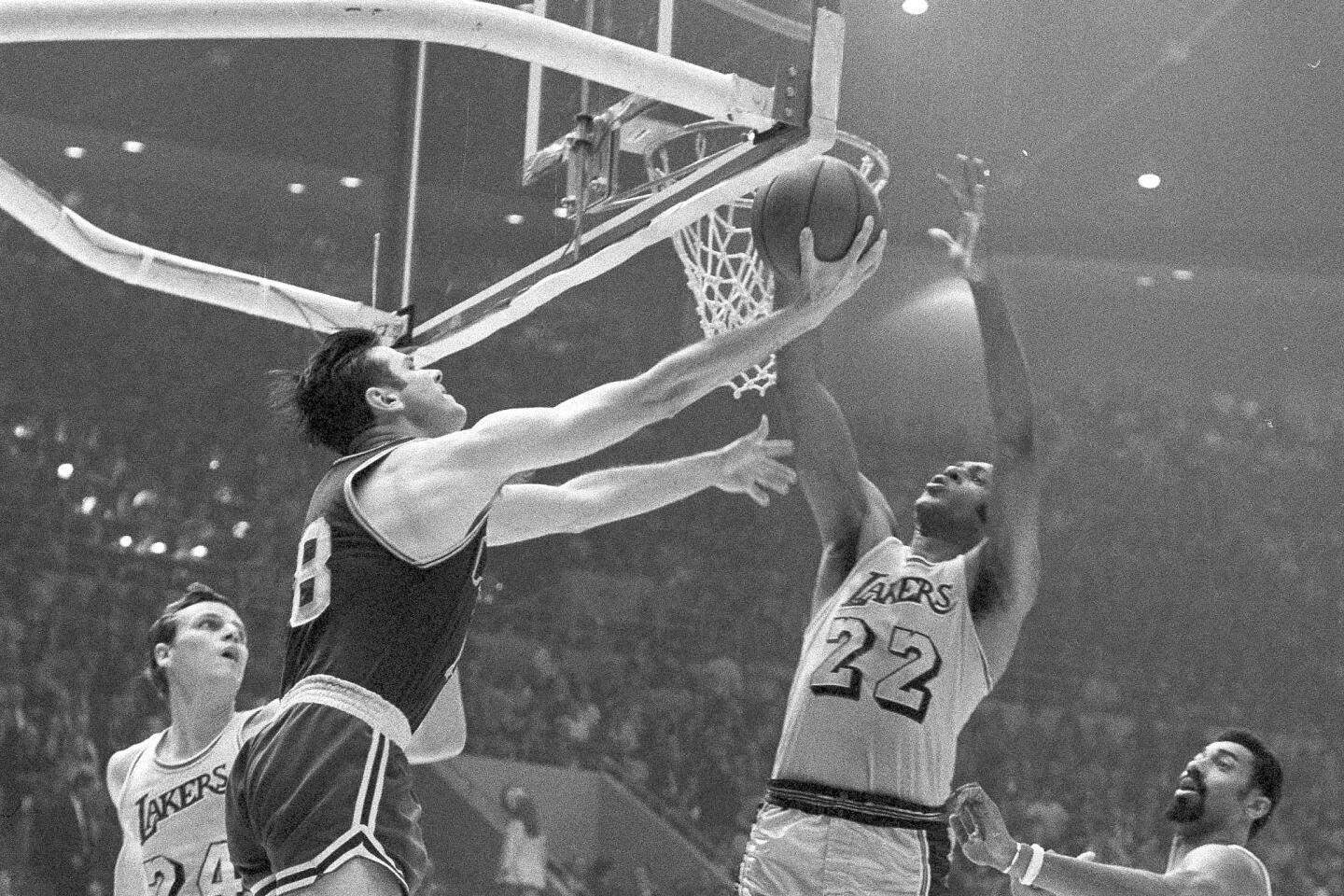

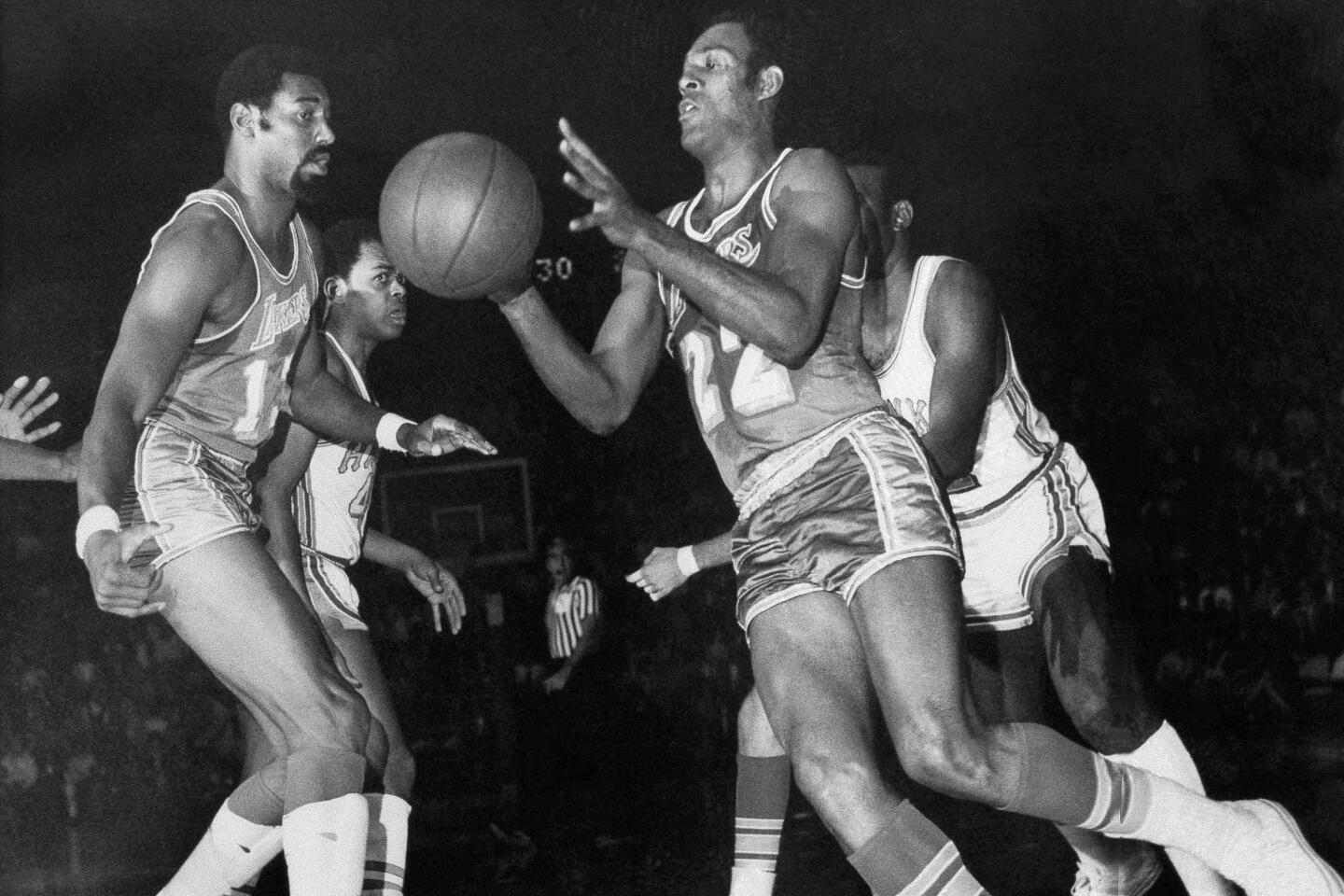

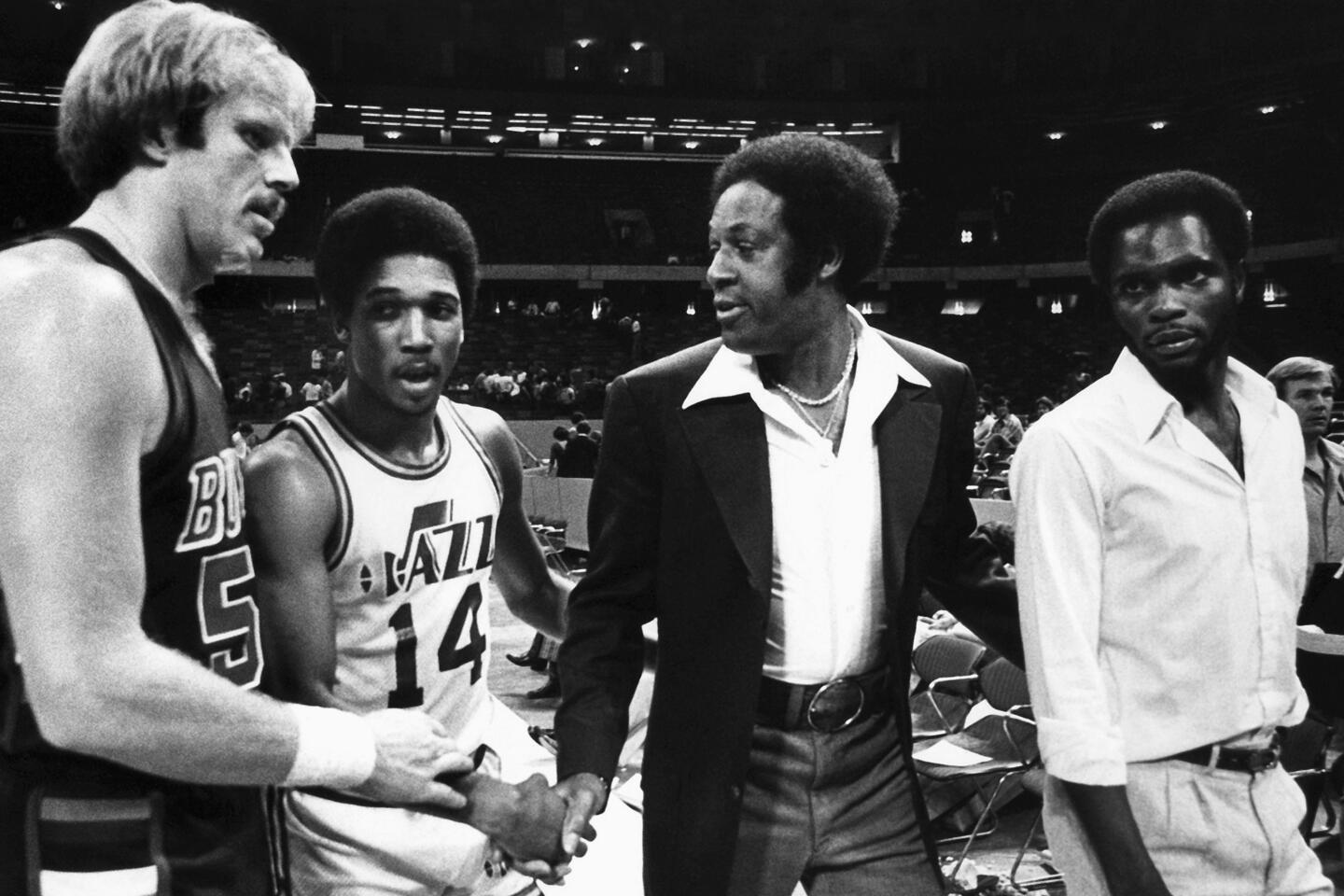

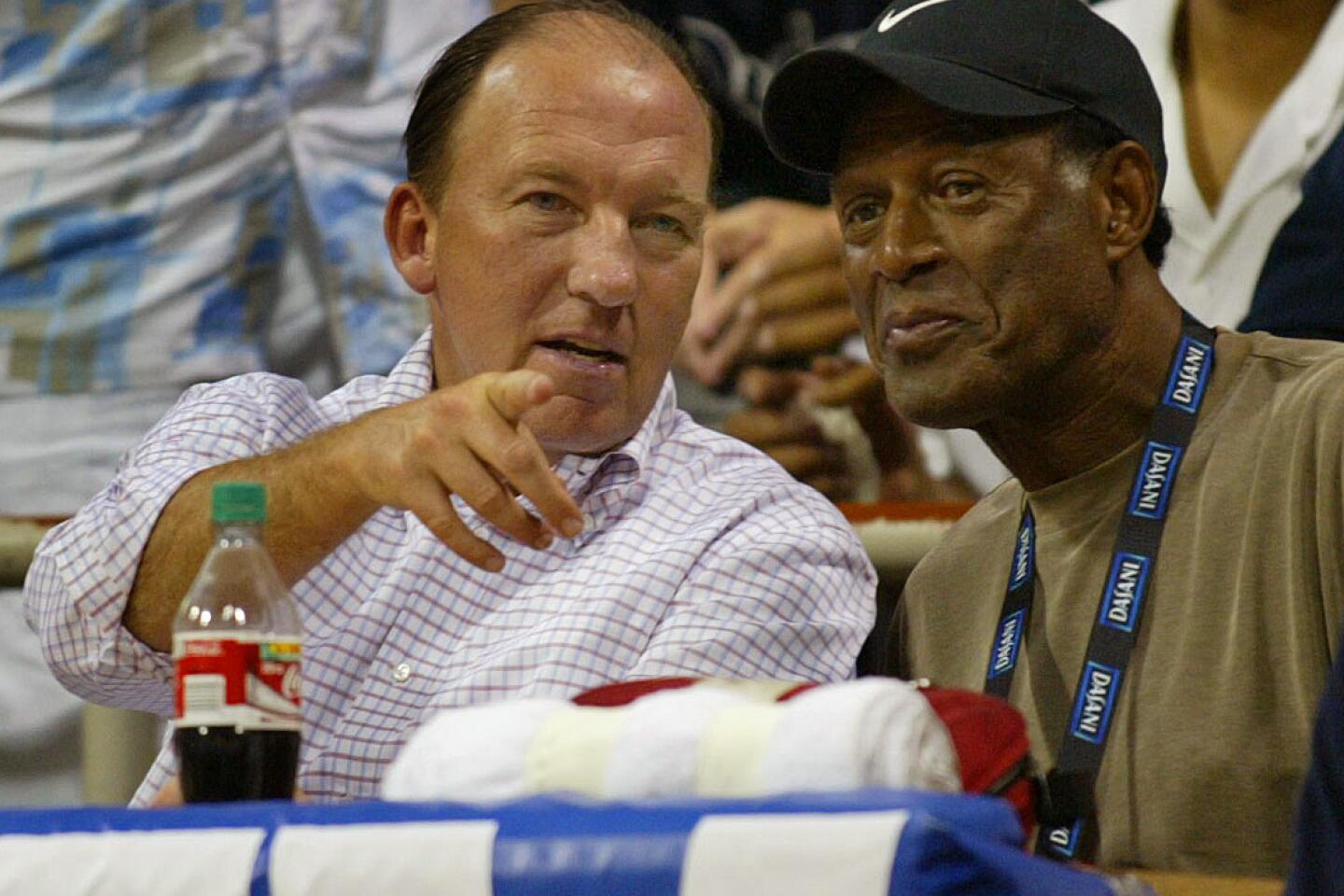

A look at the life and playing days of Lakers Hall of Famer Elgin Baylor, who would become an executive with the Clippers.

Several years after Baylor’s lawsuit, similar racial allegations resurfaced in the NBA’s investigation that led to Sterling’s banishment. But by then, Baylor’s racial discrimination claims had been dropped and the lawsuit dismissed in 2011.

At the time of the suit, Baylor could not be hired by the Lakers, so he spent two years in professional limbo. By the time suit was dismissed, the Lakers had no appropriate position for him, and he didn’t appear interested in an honorary role.

“It would be a really fine gesture but I don’t know what I would say,” Baylor told me several years ago. “I really like my life.”

But make no mistake. He spent the rest of that life not as a Clipper, but as a Laker.

“Every place I go, everyone looks at me as a Laker; that’s how I started, that‘s where I am now,” he said. “Nobody mentions the Clippers.”

Few realize it, but he is currently as much a part of the Lakers as the shirts on their back.

The Lakers’ blue “City Edition” uniforms this season were designed in Baylor’s honor, as throwbacks to when he first arrived here with the team from Minneapolis.

When fans finally are allowed inside Staples Center, here’s guessing those uniforms will get a standing ovation.

Maybe, hopefully, somehow, Elgin Baylor will hear it.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.