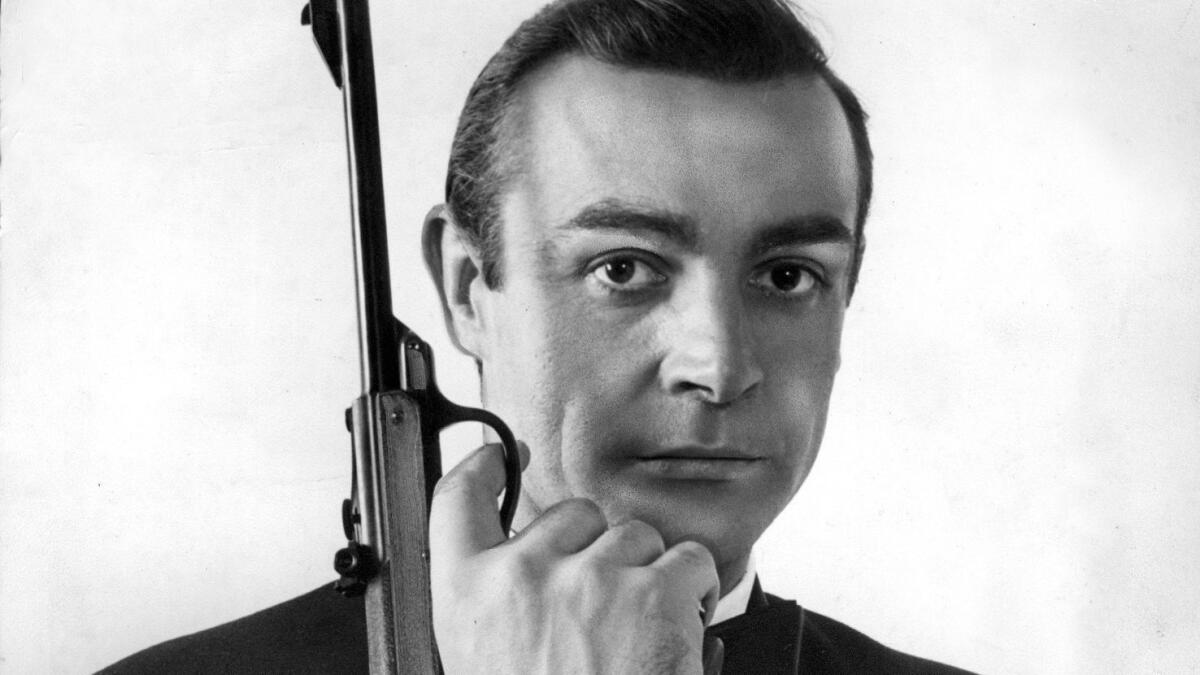

Sean Connery dies at 90, Scottish actor played the original James Bond

- Share via

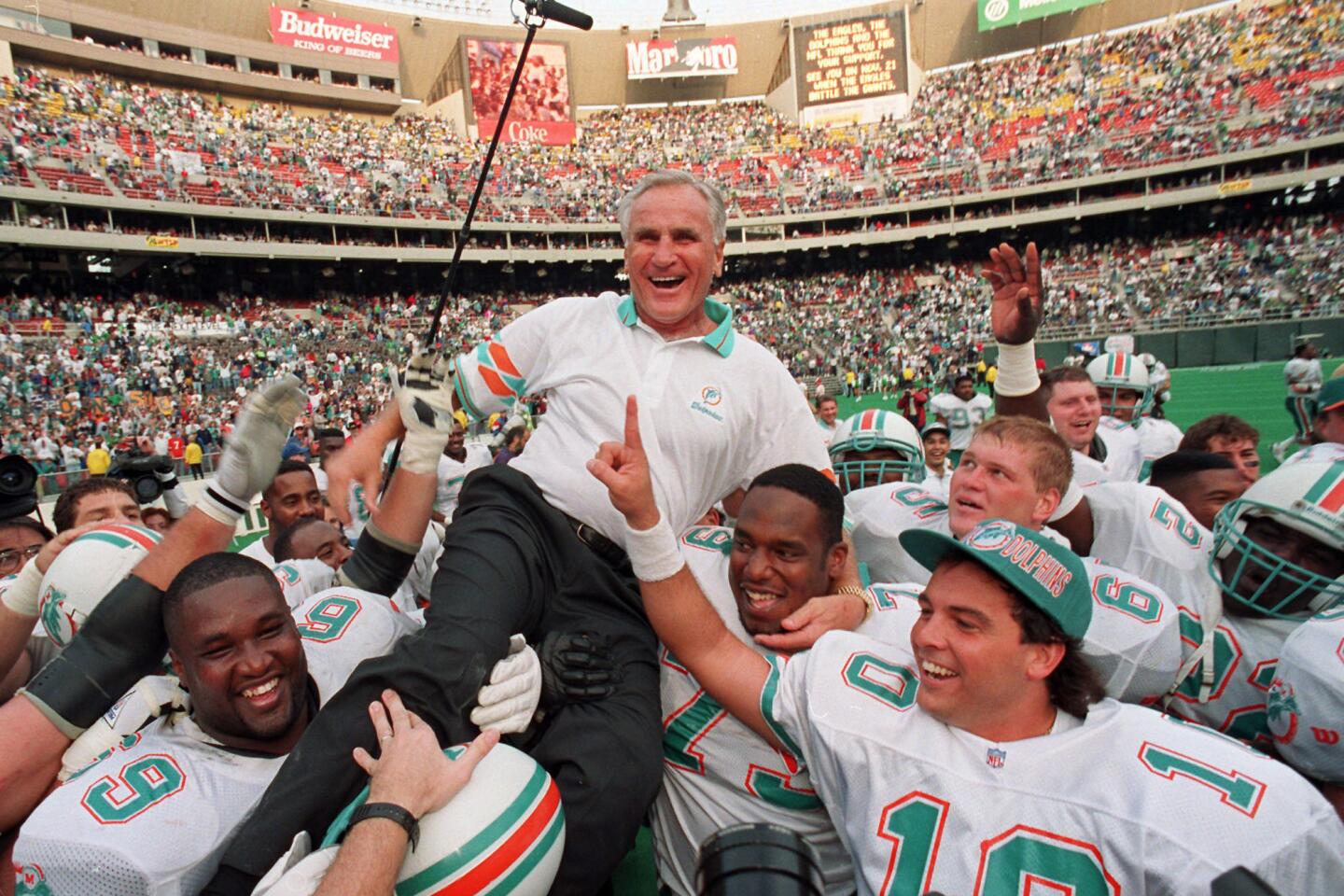

Cool as cool could possibly be, Sean Connery introduced himself to movie audiences around the world in the most succinct of ways: “Bond. James Bond.”

Connery won awards by the armful and drew praise for his roles in films such as “The Untouchables” and “The Hunt for Red October,” but he was forever tied to his turns as super spy 007, who preferred his martinis shaken, not stirred, and wiggled out of the most diabolical schemes to cripple Her Majesty’s Secret Service by eliminating Bond.

When Connery stepped away from the role, the studios spent decades hunting for his replacement — Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan among them — but the actor would always be the first and perfect James Bond.

Never out of the spotlight for long, Connery died peacefully in his sleep overnight at his home in the Bahamas, his wife and two sons told the Associated Press on Saturday. His son Jason said his father had been in poor health. The actor was 90.

“He revolutionized the world with his gritty and witty portrayal of the sexy and charismatic secret agent,” longtime James Bond producers Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli said in a statement. “He is undoubtedly largely responsible for the success of the film series and we shall be forever grateful to him.”

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said Scotland, where Connery was born and raised, was in “mourning.”

A commanding screen presence throughout his long career, Connery came to define British novelist Ian Fleming’s dashing and deadly secret agent. The actor first took on the role of the impossibly sophisticated and always elegantly dressed Bond in “Dr. No,” the 1962 action-thriller that launched one of the most successful movie franchises of all time.

Connery played Bond in six more films: “From Russia With Love” (1963), “Goldfinger” (1964), “Thunderball” (1965), “You Only Live Twice” (1967), “Diamonds Are Forever” (1971) and — after vowing to leave Bond behind — “Never Say Never Again” (1983).

“For most people, the first Bond was the best, and it’s not that the others weren’t great, but Sean Connery put a stamp on it,” film scholar and author Jeanine Basinger, who headed the film studies program at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn., told The Times.

Noting the “sly, tongue-in-cheek humor” that Connery injected into the role, Basinger said that “so many great male stars, whenever they can bring that element of humor into their persona, somehow it gives them a longevity. They take the role beyond the hero, the action figure, and make it human.”

Other actors who played Bond had the humor, Basinger said, but Connery’s Bond also had “the cruel edge, the authentic sort of danger that was associated with the books.”

Connery acknowledged that crucial ingredient, telling the Chicago Sun-Times in 1996: “The person who plays Bond has to be dangerous. If there isn’t a sense of threat, you can’t be cool.”

The phenomenal success of the Bond films inspired other spy flicks such as James Coburn’s “Flint” spoofs and the “Matt Helm” films starring Dean Martin, as well as a spate of TV series, including “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.,” “The Girl From U.N.C.L.E.,” “Get Smart,” “Mission: Impossible” and “I Spy.”

More than three decades later, Connery was the hairy-chested inspiration for Austin Powers, the outrageously funny British secret agent created and played by comedian Mike Myers in a series of spy-movie spoofs.

When Connery received the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award in 2006, the Canadian-born Myers, wearing a kilt in Connery’s honor, told the actor that he was “my dad’s hero because you are a man’s man.”

Indeed, and therein lies Connery’s enduring appeal to both male and female moviegoers.

As film critic Pauline Kael told People magazine in 1989: “Connery looks absolutely confident in himself as a man. Women want to meet him, and men want to be him.”

In 1989, the same year Connery appeared as Harrison Ford’s white-bearded father in “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade,” People magazine proclaimed the then-59-year-old actor to be the Sexiest Man Alive.

Director Steven Spielberg once told GQ magazine earlier that year: “There are only seven genuine movie stars in the world today, and Sean is one of them.”

Although the Bond films brought him unexpected fame and fortune, Connery balked at being known only as 007.

Even during the 1960s peak of Bondmania, he starred in films such as Alfred Hitchcock’s psychological thriller “Marnie,” Sidney Lumet’s World War II drama set in a British military prison “The Hill,” and Irvin Kershner’s offbeat comedy “A Fine Madness.”

“I am not James Bond,” a frustrated Connery told the press before flying to Japan to shoot his fifth Bond epic, “You Only Live Twice” (1967), which he announced would be his last time playing 007. But Connery returned to the role two years later in “Diamonds Are Forever.”

Among the inducements: a then-princely $1.25 million and a percentage of the film’s gross profits. He reportedly donated his entire salary for the film to the Scottish International Education Trust, a foundation he co-founded in 1970 to provide scholarships for underprivileged Scottish youth.

Connery, however, turned down a reported $5 million to star in the next Bond film, “Live and Let Die,” in which Roger Moore took over the role of Bond.

During the ‘70s, he helped kick his Bond image in a string of films, most notably including “The Wind and the Lion,” “The Man Who Would Be King” and “Robin and Marian.”

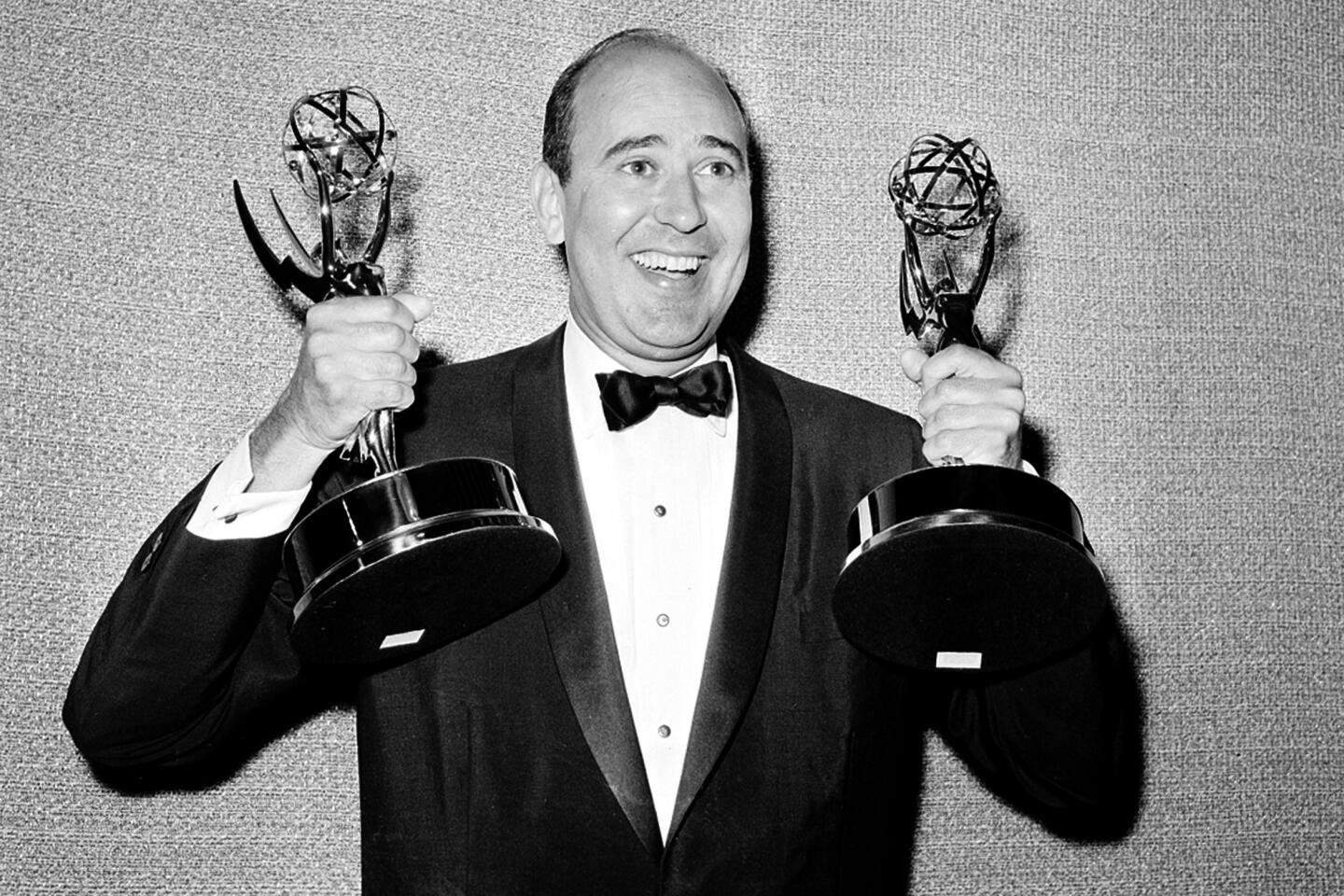

In 1988, Connery took home the Oscar for best actor in a supporting role as the aging, streetwise Irish beat cop Jimmy Malone in “The Untouchables.”

Over the next dozen years, he continued to work frequently in films, including “The Hunt for Red October,” “The Russia House,” “Medicine Man,” “Just Cause,” “The Rock,” “Playing by Heart,” “Entrapment” and “Finding Forrester.”

He also was an executive producer or producer on more than a half dozen films, from “Medicine Man” (1992) to “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (2003).

In his later years, Connery received numerous accolades, including a Kennedy Center Honor in 1999.

His support of the Scottish National Party, which campaigns for Scottish independence, was believed by some to have long delayed his knighthood, which finally came in 2000, making him Sir Sean Connery.

Connery reportedly decided to retire from acting in 2005, although he provided the title voice for the 2006 animated comedy short “Sir Billi the Vet.” He reportedly turned down portraying Gandalf in “The Lord of the Rings” series.

The eldest of two sons, Connery was born Thomas Connery in Edinburgh, Scotland, on Aug. 25, 1930. He grew up in a cold-water flat in a poor, primarily industrial section of the city, where his father was a factory worker and a long-haul truck driver, and his mother worked as a domestic.

To help out his family financially when he was 9, Connery got a job delivering milk in a handcart before school and working a few more hours after school as a butcher’s assistant. At 13, he dropped out of school and went to work full-time as a milkman driving a horse-drawn cart.

At 16, he signed up for active duty in the Royal Navy. Returning to Edinburgh, the 19-year-old Connery began working a variety of jobs, including delivering coal and working in a steel strip mill — as well as working as a furniture and coffin polisher, cement mixer, ditch digger and lifeguard.

In his spare time, he took up weight lifting and earned extra money posing as a model at an art school. At the urging of a fellow weightlifter, he entered the Mr. Universe contest in London in 1953.

Connery placed third in the tall man’s division, but his stay in London had a life-altering outcome: Hearing that auditions were being held for a touring production of the hit musical “South Pacific,” he auditioned for — and was hired — as a member of the chorus.

During the tour, Connery worked his way up to the small role of Lt. Buzz Adams and adopted the stage name Sean Connery.

Small stage and television roles followed, as did small parts in the 1957 films “No Road Back,” “Hell Drivers” and “Time Lock.”

Television offered Connery his first big break: Landing the part of washed-up boxer Mountain McClintock in a live 1957 BBC production of Rod Serling’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight” after Jack Palance had to back out to make a film.

The day after Connery delivered what one critic called “a shattering performance,” he was flooded with offers, including one from 20th Century Fox, which signed him to a seven-year contract.

While on loan to Paramount, he played an ill-fated BBC radio reporter opposite Lana Turner’s American newspaper columnist in “Another Time, Another Place,” a 1958 World War II romantic drama shot on England. And on loan to Disney, he made his first trip to Hollywood to co-star in the 1959 family film “Darby O’Gill and the Little People.”

But his association with Fox did little to further his career. Before being released from the contract, Connery appeared in several films on loan, including “Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure.”

He also played a small role in Fox’s major World War II film “The Longest Day.” But by the time it was released in U.S. theaters , Connery had been hired to play Bond and “Dr. No” was having its London premiere.

A self-described Hollywood outsider who had homes in Marbella, Spain, and Nassau, Bahamas, among others, Connery valued his privacy and shunned personal bodyguards and publicists.

He also had a long history of filing lawsuits against movie studios over money matters, including joining his “The Man Who Would Be King” co-star Michael Caine in taking successful legal action against the distributor for not receiving their full share of the film’s profit.

Over the years, Connery was dogged by allegations that he was a chauvinist, in part due to a controversial statement he made in a 1965 Playboy interview when he was asked how he felt about roughing up a woman, as Bond sometimes had to do.

“I don’t think there is anything particularly wrong about hitting a woman — although I don’t recommend doing it in the same way you’d hit a man,” he said. “An open-handed slap is justified — if all other alternatives fail and there has been plenty of warning.”

The slapping quote resurfaced from time to time, including during a television interview in the 1980s with Barbara Walters, who asked whether Connery thought slapping a woman was “good.”

“I don’t think it’s good,” he replied, “but I don’t think it’s bad. It depends entirely on the circumstances ... “

Asked if he ever slapped his wife at the time, Micheline, he said: “She doesn’t provoke it.”

Connery is survived by his wife Micheline Roquebrune, sons Jason and Stefan, and a brother, Neil.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

Times staff writer Steve Marble contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.