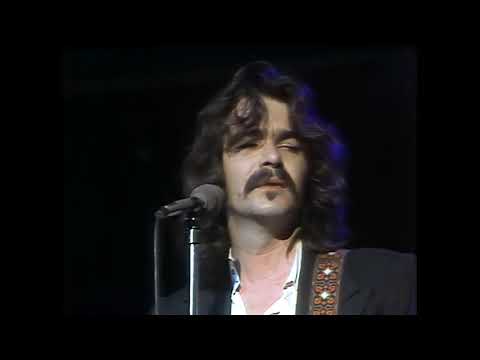

John Prine, revered singer-songwriter, dies of COVID-19 complications at 73

- Share via

John Prine, who traded his job as a Chicago mail carrier to become one of the most revered singer-songwriters of the last half-century, died on Tuesday of COVID-19 complications, after surviving multiple bouts with cancer. He was 73.

Prine died at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. His family announced his death.

Since he broke through onto the folk scene with his 1971 self-titled debut album, Prine was hailed by critics and his musical peers for his keen observational powers, mordant sense of humor and finely wrought portraits of the human condition, from his trenchant tale of a Vietnam vet’s downward spiral upon his unceremonious homecoming (“Sam Stone”) to his empathetic expressions of the loneliness of old age (“Angel From Montgomery” and “Hello in There”).

Former Times staffer Robert Hilburn opines that from his debut album in 1971, John Prine, who recently died, was one of the greatest songwriters America has ever produced.

He had been hospitalized on March 26 in Nashville with coronavirus symptoms, on the heels of previous hospitalizations for heart issues, in addition to treatments for throat cancer in 1998 and lung cancer in 2013. Both affected his singing voice, but he continued touring regularly up through last year.

“This is hard news for us to share,” his family said in a statement posted on social media on March 29. “But so many of you have loved and supported John over the years, we wanted to let you know, and give you the chance to send on more of that love and support now. And know that we love you, and John loves you.”

The statement said his symptoms came on suddenly and he was intubated on March 29, at which time he was listed in critical condition.

Earlier this year Prine was given the Recording Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award at the 62nd Grammy Awards ceremony. Over the years he was nominated for 11 Grammys and won twice. In 2005, at the request of U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser, Prine became the first singer-songwriter to read and perform at the Library of Congress.

In 2019, he was elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

Bob Dylan counted Prine among his favorite songwriters, telling an interviewer in 2009: “Prine’s stuff is pure Proustian existentialism. Midwestern mind-trips to the Nth degree. And he writes beautiful songs. I remember when Kris Kristofferson first brought him on the scene. All that stuff about ‘Sam Stone,’ the soldier-junkie-daddy and ‘Donald and Lydia,’ where people make love from 10 miles away. Nobody but Prine could write like that. If I had to pick one song of his, it might be ‘Lake Marie,’” a reference to a 1995 song from his “Lost Dogs and Mixed Blessings” album.

As Dylan indicated, Prine was championed early by Kristofferson, who touted his songwriting while Prine was still playing folk clubs in Chicago in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

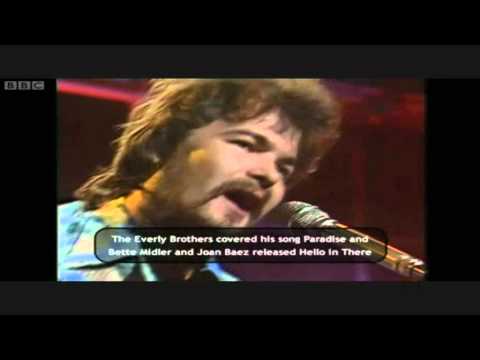

His eponymous debut album included songs that Bette Midler and Bonnie Raitt would soon bring to much broader audiences through hit versions of “Hello in There” and “Angel From Montgomery,” respectively.

That album, and those songs, set the tone for much of his career: gently rolling ballads of striking depth, often set to his own fingerpicked acoustic guitar accompaniment.

Bill Withers, who died this past week, and John Prine, now hospitalized with COVID-19, rose from working-class roots to become touchstone singer-songwriters.

Another song from that debut album, “Paradise,” lamented the devastation of the natural beauty of Kentucky by the coal mining companies and has become a modern-day bluegrass standard. It has been recorded by dozens of artists, perhaps most notably by the Everly Brothers, who hailed from the same western Kentucky region the song celebrates:

Daddy won’t you take me back to Muhlenberg County

Down by the Green River where Paradise lay

Well, I’m sorry my son, but you’re too late in asking

Mister Peabody’s coal train has hauled it away.

Tom Hanks, Rita Wilson, Pink, Idris Elba, Daniel Dae Kim, Andy Cohen and more have gone public with coronavirus diagnoses. And the list is growing.

“Since the rise of Kris Kristofferson, there must have been 150 albums by new artists in roughly the same folk/country tradition,” Los Angeles Times pop music critic Robert Hilburn wrote upon that album’s release almost 50 years ago, “but I don’t recall any of them being as exciting as the debut album from 25-year-old John Prine.” The album earned him a Grammy nomination for best new artist at the 1973 ceremony.

That album was no fluke — in the ensuing half-century, Prine wrote hundreds of songs and released more than a dozen studio albums, earning himself a place as one of the esteemed practitioners of Americana music.

A new generation of Americana and progressive country singer-songwriters regularly sang his praises, among them Kacey Musgraves (who wrote and recorded a song about her fantasy meeting with him, “Burn One With John Prine”), Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson, Margo Price and Brandy Clark.

His songs have been recorded by a phalanx of country, folk and rock stars, from Johnny Cash and Miranda Lambert to John Denver and Carly Simon to 10,000 Maniacs and the Replacements’ Paul Westerberg.

Prine spun out some of the most haunting sketches of compelling characters since Mark Twain, to whom both his humor and insights into the human condition were often compared.

“There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes,” from 1971’s “Sam Stone,” was the way Prine powerfully crystallized so many military vets’ experience upon returning home from Vietnam — for the lucky ones who didn’t die there.

On a lighter but still poignant note, he exquisitely captured the emotional distance between a long-married couple on 1986’s “Linda Goes to Mars” with the lines: “I just found out yesterday that Linda goes to Mars / Every time I sit and look at pictures of used cars / She’ll turn on her radio and sit down in her chair / And look at me across the room, as if I wasn’t there.”

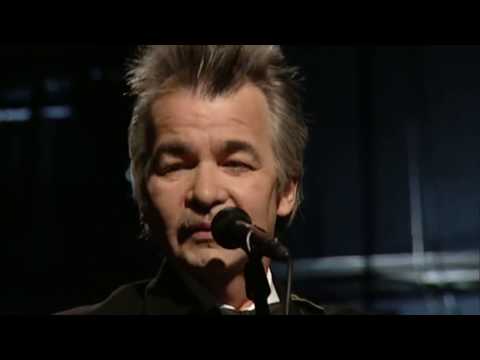

Dwight Yoakam added more than just extra star power to Saturday’s multi-artist salute to veteran singer-songwriter John Prine.

He focused an unsentimental eye on everything he wrote, including his own mortality in the wake of his brushes with death from cancer. On his most recent album, “The Tree of Forgiveness,” released in 2018, he included “When I Get to Heaven,” a song in which he imagined reaching the Pearly Gates, hoisting a cocktail and firing up “a cigarette nine miles long.”

As he explained to The Times in an interview when the album was released, “Surely they don’t have ‘No Smoking’ signs in heaven. I really miss smoking cigarettes. I gave them up the night before I had my neck surgery…. But I never stopped thinking about it. I thought, ‘Where in the hell can I smoke cigarettes? It’s not going to be anywhere down here.’ So I thought, maybe when I get to heaven I can smoke cigarettes.”

Four decades earlier, he’d recorded “Illegal Smile,” an ode to the joys of recreational pot smoking.

Prine also was a maverick businessman, who walked away from the major record labels to start a mail-order business of his own, Oh Boy! Records, which was an early model for the coming independent label boom of the 1990s and 21st century.

John Prine was born Oct. 10, 1946, in Maywood, Ill., to William Prine and Verna Hamm, and picked up the guitar as a teenager, with some lessons from his brother, David. After graduating high school, he spent two years in the Army and found work with the U.S. Post Office Department when he came home.

He soon discovered motivation for pursuing a music career: He quipped that he’d much prefer scraping together a living playing for tips and the occasional free beer in bars to carting mail around Chicago in the Windy City’s harsh winters.

He befriended another promising young singer and songwriter, Steve Goodman, and the two often performed together over the years, and collaborated occasionally on songs, including “Souvenirs,” which was recorded by both men as well as by Westerberg, soul-R&B singers Bettye LaVette and Maggie Bell, and the Country Gentlemen bluegrass band, from which country-bluegrass-gospel star Ricky Skaggs emerged.

Goodman’s manager, Al Bunetta, quickly added Prine to his management roster and remained in that role for more than four decades.

With cowriter Bobby Braddock, he penned “Unwed Fathers” in 1984, a song that upbraided men who abandoned girlfriends for unplanned pregnancies, while the women suffered societal judgment: “From a teenage lover to an unwed mother / Kept undercover some bad dream / While unwed fathers, they can’t be bothered / They run like water, through a mountain stream.”

A hit recording of that song by country queen Tammy Wynette was one of the high points of his career, Prine said.

His music was often focused on matters of the heart, but he did venture into social and political commentary as well. On the debut album, during the height of protests over the Vietnam War, he recorded “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore”: “But your flag decal won’t get you into Heaven anymore / They’re already overcrowded from your dirty little war / Now Jesus don’t like killing, no matter what the reason’s for / And your flag decal won’t get you into Heaven anymore.”

When he was first diagnosed with cancer in 1998, his friendship with famed early rock ‘n’ roll pioneer Sam Phillips played an important role in his treatment. Phillips was an obsessive self-learner and had delved deeply into studying different cancer facilities and specialists after his son Knox was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. His research led him to the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and Dr. Waun Ki Hong, with whom he insisted Prine consult when Phillips found out he’d been diagnosed with neck cancer.

“He said, ‘If you don’t go down to Houston, Texas, John Prine, I will come to Nashville, Tennessee, and kick your ass every mile of the way,’” Prine told Phillips biographer Peter Guralnick.

Prine’s surgery was performed at that facility, and later he would recount an anecdote about the surgeon vowing to build lead shields around his vocal cords to protect his voice during radiation treatments. “Doc — have you ever heard me sing?” Prine said of his famously raw, raspy voice. “Just do whatever you need to do to get the cancer.”

The treatment was successful, but a decade and a half later he had part of a lung removed when more cancer appeared, as well as part of his tongue during a subsequent cancer surgery. The procedures significantly altered his singing voice and physical appearance, but he was undaunted and continued touring and recording, albeit sporadically.

He and his family were thrown for a loop in 2015 when longtime manager Bunetta died suddenly of cancer in Nashville at 72.

After Bunetta’s death, Prine regrouped. His third wife, Fiona Whelan Prine, with whom he lived part of the year in Nashville, and part in her native Ireland, took over management duties, while their son, Jody Whelan Prine, picked up the reins at Oh Boy! Records.

It was only then, Prine said, that he found out that the biggest-selling recording he’d made was “In Spite of Ourselves,” a 1999 collection of duets on old country songs with several of his favorite female singers, including Emmylou Harris, Lucinda Williams, Trisha Yearwood, Patty Loveless and others. The title track, an original sung with Iris DeMent, is his most-streamed song on Spotify.

For his first release after Bunetta’s death, Prine assembled something of a sequel in “For Better, or Worse,” another group of vintage country songs with vocal partners including DeMent, Lambert, Lee Ann Womack, Alison Krauss and, as he had done before, one track with Fiona Prine. It brought him to the country charts for the first time in more than a decade.

That served as a prelude to his first album of new songs in more than a decade, “The Tree of Forgiveness.”

Upon hearing that the album had landed him three Grammy nominations in December, he told The Times: “The attention the record’s gotten has really knocked me out. That wasn’t something that was totally expected.... It’s a good feeling to have when you’re 72.

“My first Grammy nomination? I was 24,” he said. “To still be in the game now is just great.”

In addition to his wife, who had also previously tested positive for the novel coronavirus but has since recovered, and their son, Jody, Prine’s survivors include their two other sons, Tommy and Jack Prine.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.