Column: California needs to get its act together on rooftop solar

- Share via

Government officials in California and the rest of the country should be doing everything they can to support clean energy.

In a world racked by increasingly dangerous heat waves, fires and storms — not to mention startlingly deadly air pollution — it’s hard to go wrong throwing money at climate-friendly energy sources that can replace climate-disrupting coal, oil and gas.

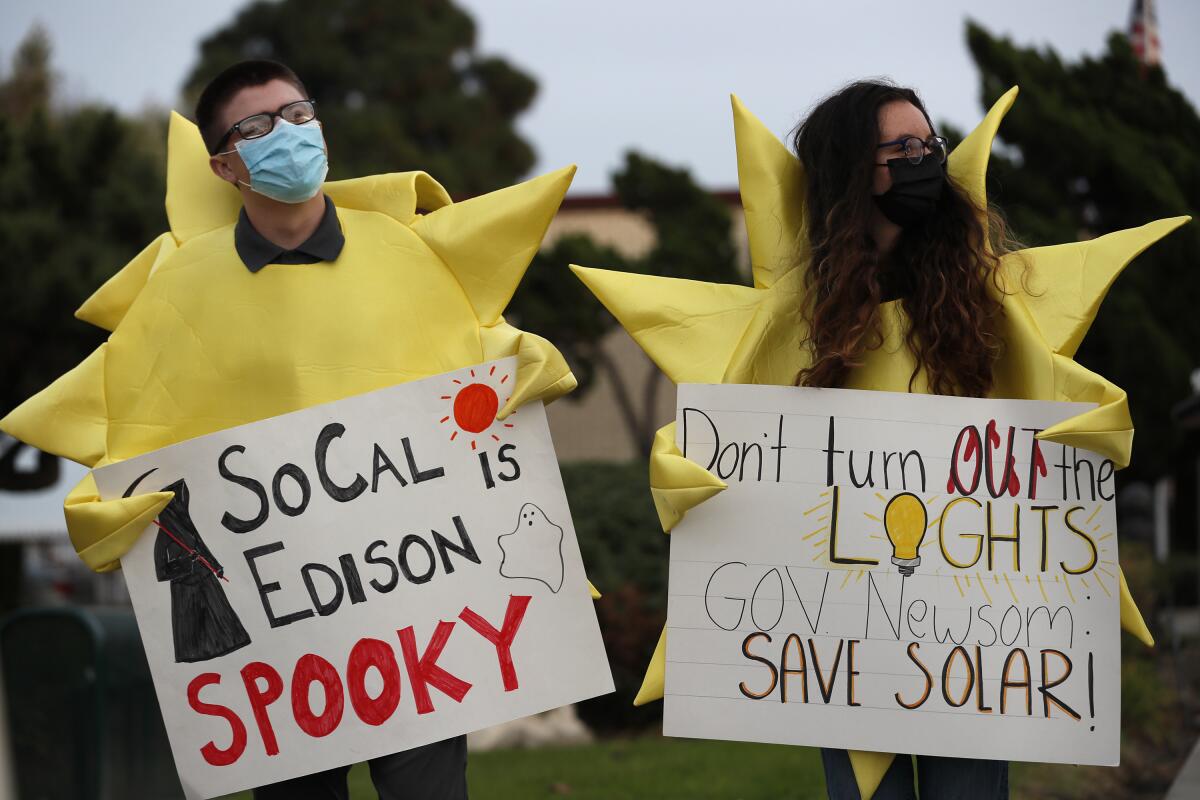

So when the California Public Utilities Commission proposed this summer to slash incentives for apartment dwellers, schools and farms that want to install solar panels — a vote is scheduled for next week— I was immediately skeptical.

You're reading Boiling Point

Sammy Roth gets you up to speed on climate change, energy and the environment. Sign up to get it in your inbox twice a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The commission’s leaders, who are appointed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, had already taken a sledgehammer to rooftop solar last year, when they voted unanimously to reduce incentives for homeowners. That decision has resulted in a steep drop-off in new installations, according to data shared with me by an industry trade group, prompting many small solar companies to say they may not be able to stay in business. San Francisco-based Sunrun, the nation’s largest installer, laid off 1,000 people.

Now California is poised to make solar less affordable for renters, critics contend — a blow not only to the state’s climate goals but also to socioeconomic equity, said Bernadette Del Chiaro, executive director of the California Solar & Storage Assn.

“We’re truly moving backwards on putting solar in the hands of everybody,” she said.

The Public Utilities Commission’s previous decision significantly cut the rate at which utility companies Southern California Edison, Pacific Gas & Electric and San Diego Gas & Electric are required to pay solar-powered homes for the energy those homes export to the electric grid. But the agency still allowed solar homes to avoid paying their utility for electricity consumed during the hours their rooftop panels are generating. During those hours, it’s assumed the electricity the panels generate is consumed on site.

Under the utilities commission proposal slated for a vote Thursday, that assumption would vanish for apartment dwellers.

Not only would their compensation for electricity exported to the grid be reduced, they would have to pay their utility company the full retail rate for all the electricity they consume — even during hours their solar panels are generating. It would essentially be assumed that they continue to rely on the utility grid even when they’re producing clean electricity.

Why the disparity?

I posed that question to Caroline Choi, senior vice president of corporate affairs at Southern California Edison. Along with PG&E and SDG&E, Edison urged the Public Utilities Commission to adopt roughly the approach that the agency has now proposed.

The utility companies have argued it’s difficult and expensive to determine precisely which families in an apartment building are using how much of a solar system’s output and when. They’ve also questioned whether such an incentive program would be fair, even if they did go through the time and expense of designing it. An apartment tenant who works from home, for instance, might be able to reduce their bills more than a neighbor who goes into an office, because solar panels produce more in the afternoon.

“It gets really complex in a multifamily building, to try to do the crediting across these different customers,” Choi said in an interview. “Is it worth that cost associated with the complexity? What it would take for the utility to calculate all those bills, and to do that in a fair way? It adds significant complexity. It adds quite a bit of cost.”

As far as many clean energy advocates are concerned, that’s a preposterous smokescreen argument designed to protect an industry that makes big guaranteed profits building long-distance electric lines and other large-scale infrastructure.

To some of those advocates, the utility industry’s argument is more than unfair — it’s unjust.

For decades, energy companies have located gas plants and other polluting infrastructure in low-income communities of color. Now state officials want to make it harder for those communities to add clean energy systems that could limit the need to keep burning fossil fuels, said Tyler Valdes, an energy equity manager at the nonprofit California Environmental Justice Alliance.

“It’s just perpetuating a legacy of environmental racism,” he told me.

Although some consumer advocates have supported the utility industry’s call to reduce solar incentives for apartment dwellers — more on that in a minute — Edison, PG&E and SDG&E are facing broader opposition in a related clean energy debate.

That debate is all about community solar — standalone solar facilities smaller than the ones getting built in the desert but larger than the ones installed on residential rooftops. The idea is that apartment renters and others who can’t install their own panels — or might not be able to afford them — can sign up to buy some of the energy generated by an off-site solar installation.

California has lagged far behind several other states on community solar, despite its professed leadership in confronting the climate crisis. That’s why Sacramento lawmakers voted last year to require a new incentive program for community solar.

The Public Utilities Commission is still developing that program. But a coalition of groups that are often at loggerheads have coalesced around a proposal they say would jump-start the industry — and they’re hopeful the commission will adopt it.

Brandon Smithwood, senior director of policy at Atlanta-based community solar developer Dimension Renewable Energy, talked me through the details. Homes and businesses would be able to sign up for a small share of a solar project. The energy produced by their share would be credited each month against their utility bill from Edison, PG&E or SDG&E, lowering their payment.

Customers would be required to send a large portion of their monthly credit back to the community solar developer — these companies need to make money, after all. But customers would still save money, with the Coalition for Community Solar Access — which developed the proposal — estimating the average low-income home would reduce its utility bills by $300 annually.

At least half of the subscribers to each community solar farm — which could be built on warehouse rooftops, open lots within neighborhoods or farther-flung desert locales — would need to be low-income homes. And in another benefit for disadvantaged communities, all community solar projects would be required to have battery systems, to store energy for after dark — meaning strategically located installations could help facilitate the shutdown of nearby gas plants, Smithwood said.

“California is blessed. It has this [gas plant] problem, but it also has the roofs to fix the problem,” he said.

The community solar proposal has won broad support from outside the solar industry — including from the Utility Reform Network, a consumer advocacy group that previously worked to slash rooftop solar incentives for homeowners.

Matthew Freedman, an attorney at the consumer group, has spent a lot of time over the years telling me how solar incentive programs can result in higher utility bills for families who can’t afford solar — an argument contested by the solar industry but accepted by state officials. The industry’s community solar proposal, though, has brought Freedman and other past opponents on board. He doesn’t agree with every provision, but he likes enough of them that he’s been speaking out in support.

One problem with the “net metering” solar incentive program slashed by state officials last year, Freedman said, was that it largely didn’t serve renters, who make up nearly half of Californians and two-thirds of low-income homes. Community solar projects can help those families — and also get built and connected to the grid much faster than sprawling desert solar farms.

“I think the [Public Utilities Commission] is going to adopt this program,” Freedman said.

He hopes the agency will signal its intent do so soon, to improve California’s odds of winning a bunch of federal money. The Biden administration is seeking applications for $7 billion in funding from last year’s Inflation Reduction Act to help low-income families access solar. California could use those funds to increase bill savings for low-income families who subscribe to community solar projects, advocates say — or to support projects that would allow for the shutdown of nearby gas plants.

In theory, a strong community solar program could help make up for cuts to “virtual net metering” — the solar incentive program for apartment dwellers, schools and farms that’s currently on the chopping block at the utilities commission.

But Alexis Sutterman, an energy equity manager at the California Environmental Justice Alliance, doesn’t see it that way. We need so much clean power to combat the climate crisis, she said, that it makes no sense to pit viable solutions against each other.

“For us, it’s an all-of-the-above approach,” she said.

Southern California Edison — the nation’s largest electric-only utility company — has laid claim to a similar mind-set. But that hasn’t stopped the company from joining with PG&E and SDG&E to oppose the popular community solar proposal.

The utilities have essentially argued that they shouldn’t have to pay for electricity sent to the grid from community solar projects at the same rates they pay for solar from residential rooftops — even the dramatically lower rates now being used by the Public Utilities Commission. From Edison’s perspective, community solar farms are fundamentally different beasts, making greater use of the utility’s power lines and resulting in more profits flowing to solar companies — at least under the industry’s proposal.

“The full benefits don’t accrue to the customer,” said Choi, the Edison executive.

To Edison’s credit, the utility has become one of California’s most powerful advocates for aggressive climate policy — in part because it stands to make loads of money for its shareholders by building long-distance power lines and other large infrastructure to support tens of millions of electric cars on the road and electric heating systems in homes.

Just last month, Edison released a white paper outlining the stupendous infrastructure build-out that it has determined will be needed for California to achieve it goals of 100% clean energy and a carbon-neutral economy by 2045. The utility assumed that the amount of “distributed solar” on the grid — including rooftop solar — will eventually double compared with today.

But on the whole, Edison and its fellow utilities see large-scale solar projects as far superior to rooftop and community solar.

The utility industry continues to point out that large solar farms benefit from economies of scale and can thus produce electricity at a far lower cost than small-scale local solar systems. And although local systems have benefits — helping people lower their electric bills and potentially keep the lights on during blackouts — those benefits have accrued disproportionately to wealthier people who can afford solar, with help from incentive programs paid for by everyone, many of whom can’t afford solar.

Equity-focused groups such as the California Environmental Justice Alliance are hopeful that better-designed programs can bring more benefits to low-income families. The utilities, though, say there are better paths forward — especially when the electric rates they charge are rising sharply, driven in part by large investments to reduce the risk of wildfire ignitions from the power grid.

“I see us as being part of the solution — putting forward proposals that we believe do serve all of our customers best, and trying to make sure that as we move toward this clean energy transition, we’re doing it in the most affordable way,” Choi said.

It’s not just Edison concerned about rising electric rates.

Although consumer advocates at the Utility Reform Network disagree with the utility on community solar, they’ve got a similar position on solar incentives for homeowners and renters, saying lower payments will help keep electric costs down for everyone else — while encouraging more families that do go solar to also install batteries, a crucial tool for California’s power grid.

The Public Advocates Office, an independent watchdog arm of the Public Utilities Commission, has a similar stance. Matt Baker, who leads that office, told me keeping electric rates down isn’t just about fairness, although that’s crucial — it’s also about making sure as many people as possible can afford the electric cars and home heat pumps so crucial to climate progress.

Baker sees upfront solar rebates, paid for out of the state budget, as the best option for lowering the costs of going solar.

“The goal should be all of us coming together to solve this climate change problem,” he said.

For the foreseeable future, unfortunately, I don’t expect too much “coming together.” Even last year’s vote to slash solar incentives for homeowners is still being contested. A state appeals court agreed last month to consider a lawsuit brought by the Center for Biological Diversity and two other groups, which believe the Public Utilities Commission’s decision violated state law.

Some Californians won’t be affected by the results of squabbling. The utilities commission’s decisions apply only to customers of Edison, PG&E and SDG&E — so if you get your electricity from a public agency such as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, the solar incentives available to you won’t change. And if you’re an Edison, PG&E or SDG&E customer who already installed solar or enrolled in virtual net metering or community solar, the incentives you receive probably won’t change for many years.

But there’s a lot at stake — especially considering a new state requirement that took effect this year, requiring all newly built apartments and condos to install solar or sign up for community solar projects. Will solar pencil out for those renters and real estate developers? If it doesn’t, what will be the consequences for the state’s larger clean energy and housing goals?

These wonky policy debates are never simple. Even in an era of climate calamity, not every proposal to subsidize or invest in climate-friendly technology is good one. We don’t have infinite money. We need to be careful. We need to make choices.

But we also need to be spending a lot more than we are today — and looking beyond traditional economics that tell us rooftop and community solar are more expensive than large-scale solar, end of story. We need all the solar we can get — lots and lots and lots of it.

It’s time to stop arguing about which climate solutions are better than others, and start coming together.

ONE MORE THING

In case you missed it, last week I became The Times’ first-ever climate columnist — and this was my first full-length column.

I’m still figuring out what it means to be a columnist, and how I want my writing to reflect that. My expectation right now is that I’ll mostly keep doing what I’ve been doing, telling nuanced stories with multiple perspectives worth exploring and letting you know how I’m thinking through the issues at play — without telling you straight up what I think the right answer is.

But we’ll see how this goes. Now and in the future, please feel free to email and let me know what you think.

We’ll be back in your inbox Tuesday. To view this newsletter in your web browser, click here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on Twitter.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.