Review: How Lucy Ives turned the ‘What’s in Her Bag’ trope into a brilliantly berserk novel

- Share via

On the Shelf

'Life Is Everywhere'

By Lucy Ives

Graywolf: 400 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“What’s in her bag?” It’s a standard question posed in women’s magazines and on YouTube. The answers are meant to give readers an intimate glimpse into a chic individual’s world: what lip gloss she uses, what novel she’s reading. In her brilliantly berserk third novel, “Life Is Everywhere,” Lucy Ives utilizes this conceit to unique effect. If we imagine, that is, that the bag in question belonged to an obsessive, freshly jilted graduate student, “nearly insane with doubt,” awash in stoner wonderment and frustrated literary ambition.

The putative protagonist is Erin Adamo, a grad student locked out of her apartment one night in New York City in the fall of 2014. But the curtain does not open immediately on Erin’s life. Instead, the novel begins with the fascinating history of the discovery of botulinum toxin, starting in the ninth century and following an unlikely path (via its commercial form, Botox) into the faces of millions of women, including a member of the English department where Erin is a student.

This disorienting but thrilling opening gambit is cinematic, like a view from space that pans swiftly down into a single pore on a human face. It prepares the reader for the wild ride ahead, for the grand sweep, the layering of chronologies, the manifold references and acts of repetition that make this novel feel at times like a vital but hard-to-follow art film.

Following the Botox history and a thorough, often hilarious accounting of Erin’s marital breakup and the current drama engulfing her department (involving an older professor and a young student, natch), the reader enters Erin’s bag. What’s in her bag? Two of her own fiction manuscripts; a monograph from 1978, complete with footnotes, authored by the controversial professor about one Démocrite Charlus LeGouffre (a fictional French novelist, but the monograph is so convincing, one takes to Google straightaway to check); a single page of academic writing by the Botoxed professor; and a Con Edison bill addressed to Erin’s erstwhile husband.

The Norwegian novelist’s latest, ‘Men in My Situation,’ has its share of male myopia but transcends when it encompasses universal conditions.

They are all here, in full, comprising roughly 250 pages of the book. It’s a move the reader might resent, but it’s pulled off compellingly. It helps that Erin’s manuscripts are at least partially autofiction. They recast events the reader already knows something about, lending the novel a sense of perpetual circling and recapitulating.

These documents represent multiple attempts, workings-through, iterations of the same material, and reading them feels tender if sometimes voyeuristic. We know, for example, that Cody, the philandering husband character in one of Erin’s manuscripts, is very similar to Erin’s husband. We are accessing her grief in another register, one that perhaps should feel more detached but actually is more immediate and sad.

In its spirited play with literary history real and imagined, “Life Is Everywhere” bears a resemblance to Shola von Reinhold’s extraordinary 2020 novel, “LOTE.” Ives’ story-within-a-story also recalls “1001 Arabian Nights,” Vladimir Nabokov’s “Pale Fire” and Laurence Sterne’s “Tristram Shandy.” Is one of Erin’s characters named Hamlet because of the play-within-a-play in the ”Hamlet”? Is LeGouffre an echo of Baudelaire’s poem “Le Gouffre” (gouffre is abyss in French) in “Les Fleurs du Mal”? (This LeGouffre attends Baudelaire’s funeral in the fictional monograph!) Or have we simply fallen into our own abyss?

Ives also presents an array of possible readings of her own work. Peppered throughout one of Erin’s manuscripts are reading comprehension exercises, an alcoholism self-assessment and a dream journal titled “Hypergraphia” (a behavioral condition marked by a compulsion to write). We know Erin’s maternal grandmother may have been a sufferer, but the frequent mention of the disorder also functions as a self-own. Just as the reader begins to suspect Ives is constitutionally incapable of cutting pages or paragraphs, she throws out the specter of an actual condition that might be afflicting her main character, possibly even the writer herself.

Erin’s narrator also nurses an obsession with the German conceptual artist Hanne Darboven, who made large-scale installations of tables of handwritten lines and numbers. These acts of serialization offer a comfort to Erin’s narrator and, maybe, like the multiple manuscripts herein, a key to the book the reader holds in her hands.

Julia May Jonas’ “Vladimir” is a thrilling “Lolita” update in which the deliciously wicked narrator is not the male abuser but his wife.

“Life Is Everywhere” has a lot in its bag, but at heart it is a novel of academia, situating itself within a long, neurotic tradition of arduous, insular intellectual labor and petty competition among scholars. Its depiction of department dynamics is so pitch perfect as to be truly disconcerting to anyone with personal experience. A professor in a “lurid, floor-length paisley skirt” can be seen “glowering in the corner under a stack of muted raw-silk scarves.” A fellow grad student, “brittle and wan and proud,” makes Erin feel bad about herself, ever announcing her participation in a conference or roundtable on “the figure of the clerk in whatever.”

“Erin did not want to be Alana Harris—and she certainly did not want to be like her,” Ives writes of this student. And yet, she wanted to possess the kind of “potent delusion” that made Alana Harris so productive. (“Grad school!!” this reader wrote in the margin.) In spite of its many forays into philosophy and even mysticism, these grindingly real, almost cringeworthy passages ground the novel.

Sometimes, however, the asides feel excessive. Erin enters the university library, and four pages follow on the life of the antisemitic architect who designed it in the 1970s, students who committed suicide there, the installation of panels to prevent similar future tragedies and the way the panels “symbolized the movement of data as zeros and ones.” It’s a lot. Ives is capable of virtuosic control — there are at least 10 different kinds of writing in this book, and all are carried off so masterfully it’s almost frightening. At the same time, this is a work of art that feels like a barely contained explosion.

But this unhinged campus novel is, to use a campus word, generative. It’s “good to think with” on a vast range of topics: the chauvinism of a strain of literary criticism, the ineffaceable damage done by families of origin, why we can never again recapture the happiness we felt in old relationships or even fully understand why we were actually there, to say nothing of why we are here now. In many instances, Erin seems to lose touch momentarily with the thing we call reality, and those moments feel the most real of all. “Phenomenal reality bobbed,” Ives writes. “It bounced, jiggled.”

Novelist Lynn Steger Strong on the revolutionary passivity of Rachel Cusk, Ottessa Moshfegh and Sally Rooney — how we’ve misread them and what comes next.

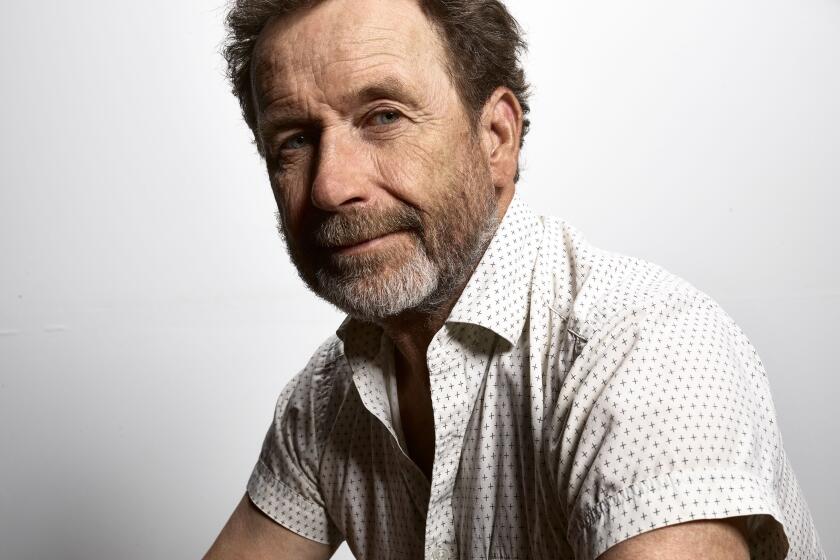

Aron is the author of “Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls: A Memoir of Women, Addiction, and Love.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.