Review: Not just another sad-man novel: Why Per Petterson is worth your time

- Share via

On the Shelf

Men in My Situation

By Per Petterson

Translated by Ingvild Burkey

Graywolf: 304 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

We’re living in a moment of depleted patience for the beleaguered man. Drinking and womanizing got you down? Boo hoo. Wife left you after years of emotional neglect to care for your children alone? Cry me a river. So it is with some skepticism that a woman book critic in the year 2022 picks up a novel called “Men in My Situation” about an aloof, sullen, recently divorced man approaching middle age.

Fortunately, this one is written by Per Petterson, a master at capturing internal tumult, family relationships and the vicissitudes of grief and a novelist whose men are never simple. Petterson’s eighth novel, translated by Ingvild Burkey, tells the story of Arvid Jansen, a 38-year-old father of three girls and a writer who dwells in a state of perpetual bewilderment. Even in the city where he’s spent his whole life, he is out of place, his sensibility somewhat askew. “Well hello there Knut Hamsun,” old friends say as he enters the bar. But Arvid thinks, “Nothing that I had written pointed towards Hamsun, not as I saw it.”

Arvid has split with his wife, Turid, who now lives with their daughters. He searches for a trace of himself in Turid’s new home but finds nothing, noticing only a familiar cabinet she had painted “an insistent blue, to remove all memories.” So he goes out at night, wandering among Oslo’s bars looking for distraction or affection. Or he drives around in his Mazda, or sits at home smoking unfiltered Blue Master cigarettes and listening to Mahler’s funeral march, the dotted rhythms of which would form a good soundtrack for the scenes of everyday frailty and futility that fill the novel.

There is a degree of self-mocking in the titular “situation.” Divorce and disaffection are unremarkable, after all. But Arvid’s situation is also singularly devastating. Hanging over the mild action of the book is a recent horror: the deaths of four members of Arvid’s family in a conflagration on a ferryboat that killed 159 people in all.

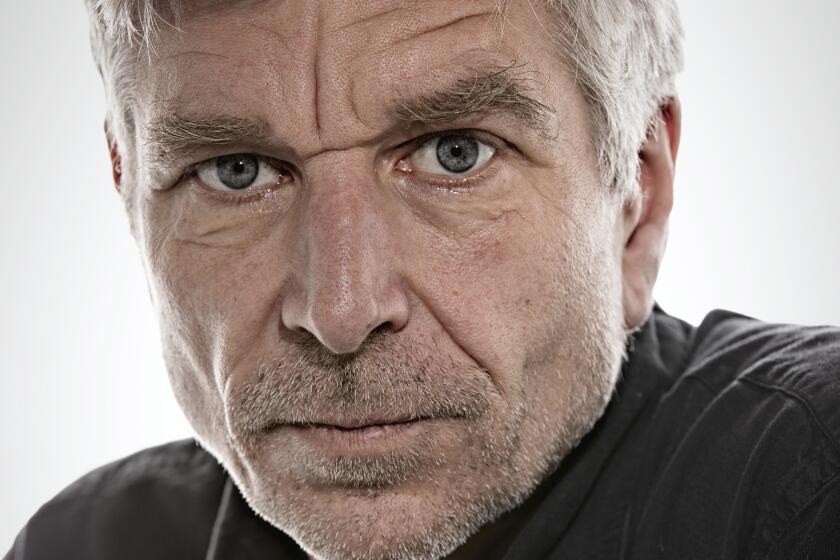

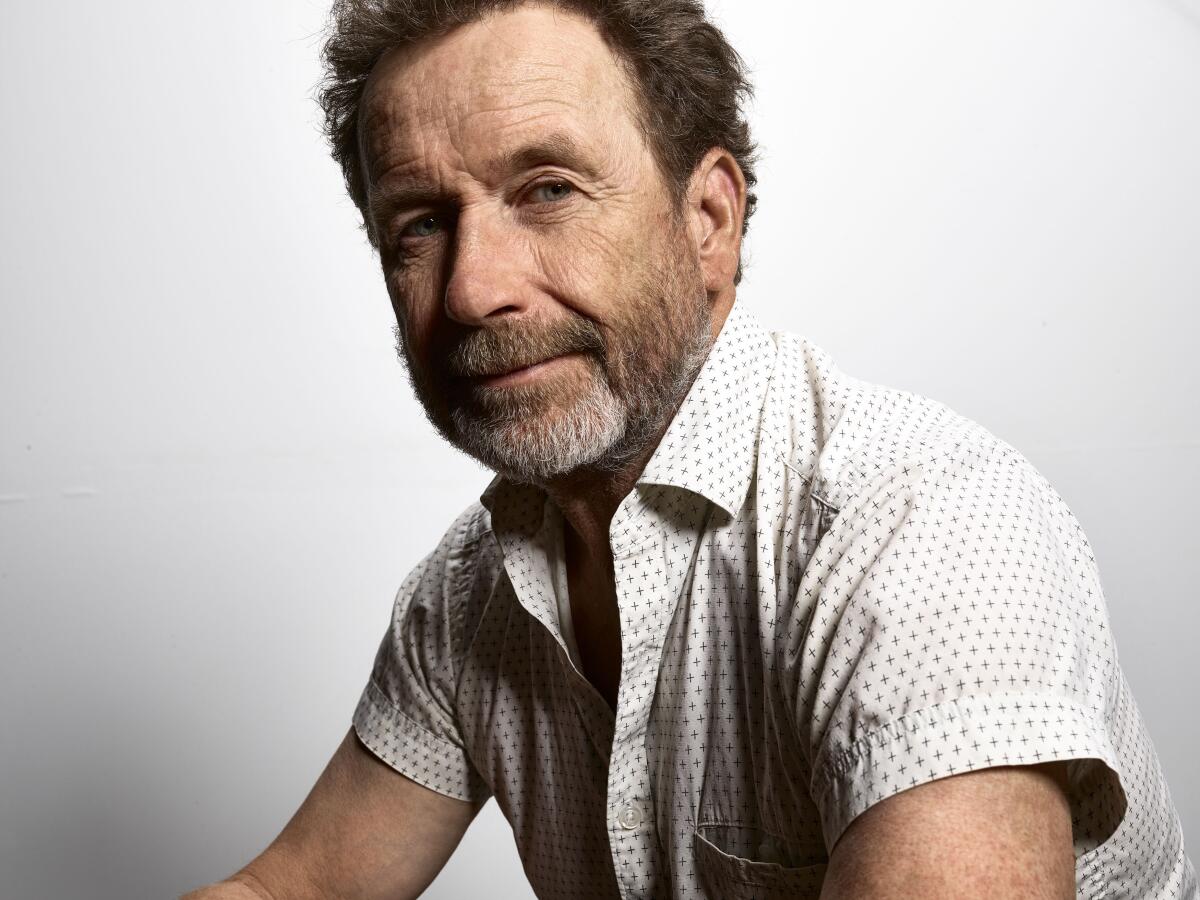

Fans of Petterson will be familiar with Arvid, who has been at the center of most of his books. They will likely also know his life closely resembles Petterson’s: The author’s parents and brother died in a ferryboat fire that claimed 159 lives in 1990. Of Arvid, however, Petterson told the Guardian in 2009, “He’s not my alter ego, he’s my stunt man. Things happen to him that could have happened to me, but didn’t.”

With the death of his parents in a ferryboat fire, Norwegian author Per Petterson is consumed with the notion of family.

While all of Petterson’s books are concerned with grief, in “Men in My Situation,” the author seems particularly interested in the uses to which suffering can be put, the ways it can be marshaled for personal gain as well as the corrosive effect it can have on relationships. In many instances, grief makes a cad of Arvid. When he finds himself unable to please a woman who has taken him home, Arvid plays “the highest card I had in the pack. I exonerated myself. I used the burning ship as a shield, I was shameless, I’m wounded, I said, that’s why.”

But for every instance of Arvid deliberately weaponizing his trauma, there are numerous others when he doesn’t know why he’s doing the things he does. He is alienated from himself, even physically — he doesn’t recognize his own body. He struggles too to understand others, including women, whose signals he seems doomed to misinterpret, and his daughters, from whom he maintains a sad distance. Eventually, they ask for real distance, and Arvid is hurt, but the reader hardly blames the girls. He does seem pretty boring to hang out with. Things change only slightly when his eldest daughter, Vigdis, needs his help toward the end of the novel and Arvid must find a way to show up.

Arvid’s tortured dealings can be annoying. His cluelessness and self-pity wear on the reader. His take on the experiences of adult women is often cliched, such as his encounter with a possibly suicidal prostitute on a quay late one night, to whom he ascribes a kind of oracular significance.

Later, he feels a brief flare of jealousy when he sees his ex-wife looking pretty and considers that she might have a new lover. Why didn’t she try to look prettier for him, he wonders, but he lets the thought go, thinking, “she deserves better than what I could give her” — the tired refrain of a low-effort man.

Still, Petterson’s depiction of post-marriage disorientation rings painfully true. The “thin white groove” where Arvid’s wedding ring used to sit is like “a mark I could never get rid of, a stigma.” Turid’s new life, including the boisterous band of friends whom Arvid resentfully calls “the colourful,” confounds him. He recalls the new songs these friends brought into their house in the years before they split. He could hear Turid weep while she sang them, “her voice close and intimate over Morrissey’s voice, to die by your side is such a heavenly way to die, and so on in that way and obviously she didn’t mean my side. I hated that music.”

In ‘The Morning Star,’ Knausgaard’s first major novel since his semi-fictional ‘My Struggle,’ psychodramas are outshined by a cosmic disturbance.

The emotional claustrophobia in these sections is reminiscent of Elena Ferrante’s ferocious “Days of Abandonment.” Arvid’s nights out, dark humor and sense of being a stranger to himself put me in mind of another romantic disaster novel, Pedro Mairal’s fantastically entertaining “The Woman from Uruguay.”

Is loss the reason Arvid is the way he is? That would be too simple, and Petterson knows it. I couldn’t help but read this latest Jansen novel through the lens of critic Parul Seghal’s recent piece in the New Yorker arguing against the totalizing quality of the “trauma plot” in contemporary fiction. Arvid’s trauma never comes across as a cheap conceit, nor as the engine powering all of his disillusionment. Flashbacks to the uneasy beginning of his relationship with Turid prove he was already detached from his emotional core, suffering from dysthymia for years prior to the ship burning.

In spite of his low mood, however, Arvid’s mind is active. In pages-long, often dialogue-heavy sections without paragraph breaks, quotation marks or full stops, Petterson shares his character’s interior monologue. The effect of cascading language mirrors Arvid’s internal state, and it ought to feel frenetic. But paradoxically a kind of desolation sinks in. As busy as Arvid’s mind is, it generates only a sense of blankness. This serves as a far better evocation of grief than some of the perfunctory sections where Petterson tries straightforwardly to describe the condition.

This paradox is perhaps the hallmark of Petterson’s work. For all its run-on sentences and muddled emotions, “Men in My Situation” is possessed of an austerity and bleakness that is satisfyingly unforgiving (and that is tempting for an American reviewer to attach to cold, northern weather conditions — but I shall resist). The hapless, deeply flawed Arvid can make no sense of the string of senseless events that make a life. And his puzzlement offers comfort, transcending middle-aged male disaffection to speak to the universal condition of adulthood.

Megan Nolan’s “Acts of Desperation,” about a woman in thrall to an older man, stands out from similar tales with an uncannily self-aware narrator.

Aron is the author of “Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls: A Memoir of Women, Addiction, and Love.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.