L.A. County’s COVID-19 emergency will end March 31

- Share via

Los Angeles County will end its COVID-19 emergency declaration at the end of March, becoming the latest region to take that step amid improving pandemic conditions.

The move, approved unanimously Tuesday by the county Board of Supervisors, came the same day Gov. Gavin Newsom formally rescinded the statewide emergency declaration issued three years ago during the onset of the coronavirus outbreak.

Like their state counterparts, L.A. County officials praised the original March 2020 proclamation for providing necessary authority and flexibility to respond to the outbreak.

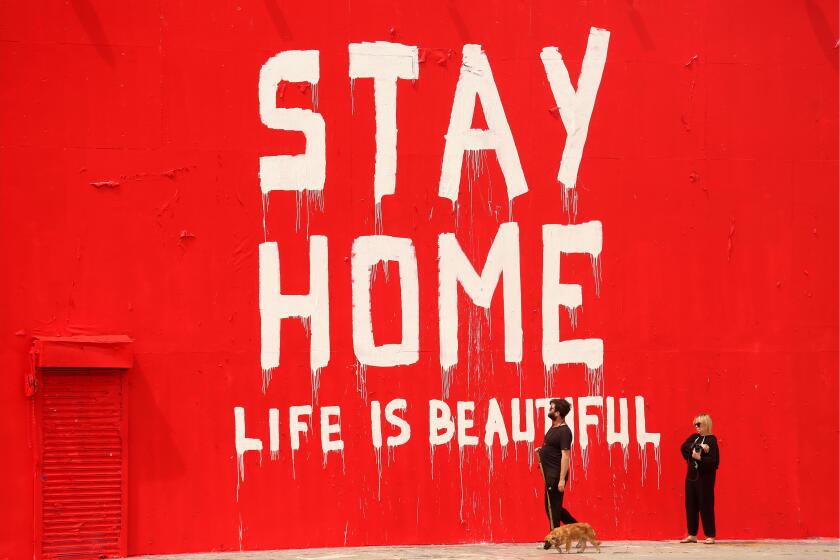

But given the current situation — with vaccines and therapeutics plentiful and hospitalization and death rates having tumbled without the sort of aggressive interventions seen earlier in the COVID-19 era, such as mask mandates and stay-at-home orders — officials said the emergency declaration was no longer necessary.

“COVID is still with us,” Supervisor Janice Hahn said Tuesday, “but it is no longer an emergency. And it’s time for us in L.A. County to end our emergency orders.”

California’s COVID-19 state of emergency ends Tuesday, bringing a symbolic close to a challenging chapter of state history and of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s political career.

The motion to end the declaration, co-authored by Hahn and Supervisor Kathryn Barger, said that it had, without question, preserved lives: “Every county department has relied on the existence of these emergency orders and health officer orders in various ways to protect against COVID-19 and provide essential services to protect the public over the past several years. It is beyond dispute that these actions saved lives and protected the health of county residents.”

“It was uncharted water,” Barger said of the pandemic, “and really none of us knew what to expect.”

The declaration, she added at Tuesday’s meeting, “was necessary to ensure our healthcare institutions had the resources and flexibility to respond quickly to the dynamic need in our community.”

Under the board-approved motion, the county’s local emergency declaration will end March 31.

“These past few years, and especially that first year before we had the vaccines, were the darkest years many of us have lived through,” Hahn said. “And I really want to take this opportunity to thank everyone in L.A. County who helped us get through to the other side.”

L.A. County has recorded more than 35,000 COVID-19 deaths since the start of the pandemic, and some areas were hit harder than others. Supervisor Hilda Solis said her eastern district reported nearly 9,000 deaths, the highest toll of any of the supervisorial districts.

“These are mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, abuelas, abuelos who are no longer at the family dining table,” Solis said. “And, of course, we all know of residents who lost their jobs, small businesses that closed their doors never to open again, and people losing their homes and falling into homelessness.”

But the ending of emergency orders doesn’t mean we should forget the pandemic’s lessons, she added.

“Stay at home if you feel sick. Get tested. Get vaccinated. And for God’s sake, get boosted,” Solis said. “It also means looking out for one another: protecting our communities that are most vulnerable, and working to address the social determinants of health” — factors including racism and poor access to medical care, quality education and safe housing — “that created significant health disparities that COVID brought to light.”

Even in a time of plentiful vaccines and therapeutics, California is still tallying more than 20 COVID-19 deaths every day, on average.

The city of Los Angeles ended its own local COVID-19 emergency declaration on Feb. 1, and the cities of Long Beach and Pasadena — which have independent public health departments — are winding down theirs as well. President Biden has also informed Congress he will rescind the national-level emergency and public health emergency declarations on May 11.

L.A. County, far and away the most populous in the nation, has been among the hardest-hit parts of California throughout the pandemic. According to data compiled by The Times, L.A. has recorded the third-highest per-capita cumulative case rate and fifth-highest death rate out of California’s 58 counties.

Officials have said a number of factors made L.A. County particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 — including the region’s poverty rate, overcrowded housing, preexisting health conditions among residents and its high population of frontline workers, who were at greater risk of on-the-job coronavirus exposure.

Such characteristics have often been cited by county health officials as rationale for moving faster and further than its Southern California neighbors in terms of implementing measures aimed at tamping down transmission.

L.A. County was among the earliest in the nation to reinstate an indoor mask mandate in response to the Delta surge — doing so in July 2021. The county also publicly contemplated reinstituting that order the following summer and autumn during spikes fueled by the super-contagious family of Omicron subvariants.

Unvaccinated people were more than seven times as likely to die from COVID-19 in Los Angeles County as those who received an updated booster during the latest coronavirus spike.

Like the rest of the state, L.A. County has seen steady improvement in many of its pandemic metrics since the winter holiday season.

For the seven-day period that ended Tuesday, L.A. County was reporting about 76 cases a week for every 100,000 residents.

That’s significantly lower than the most recent seasonal high of 272 cases a week for every 100,000 residents, set the week ending Dec. 7.

It’s also close to the autumn lull of 60 cases a week for every 100,000 residents but still higher than last spring’s low of 42 cases a week for every 100,000 residents.

A case rate of 100 or more is considered high. The pandemic record was 2,890 cases a week for every 100,000 residents, set for the week that ended Jan. 15, 2022, during the first Omicron surge.

A new CDC report found that children under 5 are being vaccinated for COVID-19 at lower rates than older children.

As of Monday, 648 coronavirus-positive individuals were hospitalized countywide — about half as many as the most recent seasonal peak of 1,308, set on Dec. 8. That total is also far fewer than the prior winter surges of 4,814 on Jan. 19, 2022; and 8,098, set on Jan. 5, 2021.

L.A. County is recording 90 COVID-19 deaths a week for the seven-day period that ended Tuesday. That’s lower than the winter peak of 164 weekly deaths recorded in January.

County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer has said a more stable death rate would be about 35 COVID-19 deaths a week. Such a number might still be difficult to accept — especially since fatalities are now largely preventable with vaccines and antiviral treatments — but would nonetheless represent stability and “indicate that our protections are really working extraordinarily well.”

By comparison, the all-time peak of COVID-19 deaths was 1,690 for the week that ended Jan. 14, 2021. The following winter, the peak was 513 deaths for the week that ended Feb. 9, 2022.

Gov. Gavin Newsom is winding down state assistance for healthcare services to migrants seeking asylum. He’s lobbying the Biden administration to increase aid along the state’s southern border.

Countywide, 81% of L.A. County residents have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and 73% have at least completed their primary series. Roughly 17.5% of county residents ages 5 and older have received an updated bivalent booster.

On Wednesday, the county will permanently shutter the standing vaccination sites at the Balboa Sports Complex, Commerce Senior Citizens Center and Norwalk Arts & Sports Complex, according to the Department of Public Health. Locations and hours of other vaccination providers are available at VaccinateLACounty.com.

COVID-19 is expected to remain a significant cause of death for some time to come, especially among people who aren’t up to date on their vaccination and booster shots, and aren’t given anti-COVID drugs such as Paxlovid when they do get infected.

About 60,000 U.S. residents have died from COVID-19 since October, a sum that’s more than triple the 18,000 estimated U.S. flu deaths over the same time period.

California’s 3-year-old COVID-19 state of emergency will lift Tuesday — a development that reflects the dawn of a next, hopeful phase of the pandemic.

Another concern is long COVID — an array of symptoms that can persist for months or years after an acute coronavirus infection — which is expected to result in a significant cause of disability in the U.S. for some time to come. A federal estimate, based on survey data, suggests 28% of people who have had COVID-19 have experienced long COVID.

Most people with long COVID experience improvements in symptoms over a long period of time, Ferrer said, but some people have experienced it as a disability that has persisted for years and has not ended.

“It’s sobering to see how so many people are still affected by long COVID nearly three years into the pandemic,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.