California’s COVID emergency is ending. How will it change your life?

- Share via

California’s 3-year-old COVID-19 state of emergency will lift Tuesday — a development that reflects the dawn of a next, hopeful phase of the pandemic, even as officials and experts say continued vigilance and preparation are necessary to maintain the current promising trajectory.

Though the global pandemic itself is not over, rescinding the health emergencies issued during the outbreak’s early days by all levels of government acknowledges the degree to which the overarching COVID threat has ebbed, allowing many residents to largely or entirely return to pre-outbreak normalcy.

With robust community immunity — both through vaccination and natural infection — the availability of updated boosters and effective therapeutics, as well as a well-worn toolbox of non-pharmaceutical interventions, many events and activities are safer today than they have been in years.

“While the threat of this virus is still real, our preparedness and collective work have helped turn this once crisis emergency into a manageable situation,” California Health and Human Services Secretary Dr. Mark Ghaly said.

Transitioning out of the COVID emergency phase could eventually spell the end of universal access to free vaccines, treatments and tests.

Since the future is not set in stone, officials and experts say it’s important to remain prepared to tackle COVID’s continuing impacts, as well as any new tricks the coronavirus may yet have up its proverbial sleeve. Rescinding emergency declarations may also change how residents access vital resources such as vaccines, treatments and tests.

“As we have experienced throughout the pandemic, there are no absolutes,” said Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer. “There’s a temptation to say the pandemic is ending and, for some, this experience is very real. For others, they continue to feel the impact daily — whether it is living with the loss of a loved one, the economic toll of the pandemic or the effects of long COVID.”

But given that “we didn’t see a large winter surge and that our hospitalization and death rates have remained stable is positive,” she added during a recent briefing. “I’m optimistic about this next phase.”

Here’s what you need to know.

Even in a time of plentiful vaccines and therapeutics, California is still tallying more than 20 COVID-19 deaths every day, on average.

Why is California ending its emergency?

Gov. Gavin Newsom unveiled the timeline for ending the state of emergency last October, saying California has built up the resources necessary to continue combating COVID-19 without the additional flexibility the declaration provided.

“The state of emergency was an effective and necessary tool that we utilized to protect our state, and we wouldn’t have gotten to this point without it,” he said in a statement at the time. “With the operational preparedness that we’ve built up and the measures that we’ll continue to employ moving forward, California is ready to phase out this tool.”

His announcement came ahead of the pivotal fall-and-winter season, when many officials and experts feared another coronavirus resurgence could renew stress on California’s healthcare system.

But while the state did see an uptick in transmission and hospitalizations in mid-autumn, it was fleeting and comparatively mild — leading to far and away the calmest winter of the COVID-19 era.

Gov. Gavin Newsom is winding down state assistance for healthcare services to migrants seeking asylum. He’s lobbying the Biden administration to increase aid along the state’s southern border.

What does ending the emergency mean?

California’s initial emergency declaration was issued March 4, 2020, and served as a prelude to more than 70 executive orders, many of which Newsom has already terminated.

“A lot of these things have been gradually winding down, as far as exemptions or emergency orders that were related to these various declarations,” California state epidemiologist Dr. Erica Pan said during an online forum this month. “There are a lot of state resources in the field that have been decreasingly utilized that we are demobilizing over time.”

Looking ahead, perhaps the biggest ramification of rescinding the emergency declaration will be changes in how residents access COVID-19 vaccines, tests and treatments. However, many Californians won’t see a seismic shift.

According to the California Health and Human Services Agency, “Californians will continue to be able to access COVID-19 vaccines, testing and therapeutics with no out-of-pocket costs” even after the state emergency ends.

California’s COVID-19 state of emergency ends Tuesday, bringing a symbolic close to a challenging chapter of state history and of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s political career.

Until Nov. 11 — six months after the scheduled termination of the national-level emergency and public health emergency declarations — Californians with private health insurance or who are enrolled in Medi-Cal “can access COVID-19 vaccines, testing and therapeutics from any appropriately licensed provider without any out-of-pocket costs, even if the provider is outside the enrollee’s health plan network,” the agency told The Times earlier this month.

Californians could be subject to cost-sharing or coinsurance amounts if they access those resources from an out-of-network provider after that date. But “if the enrollee accesses the services from an in-network provider, the enrollee will not have to pay anything out-of-pocket,” according to the agency.

A federal policy that required insurers to reimburse covered individuals for eight at-home COVID-19 tests per month will end along with the nationwide public health emergency on May 11. But in California, state lawmakers have acted to maintain this resource for most health plans regulated by the Department of Managed Health Care — which covers around 23.5 million people with private insurance or health plans managed by Medi-Cal.

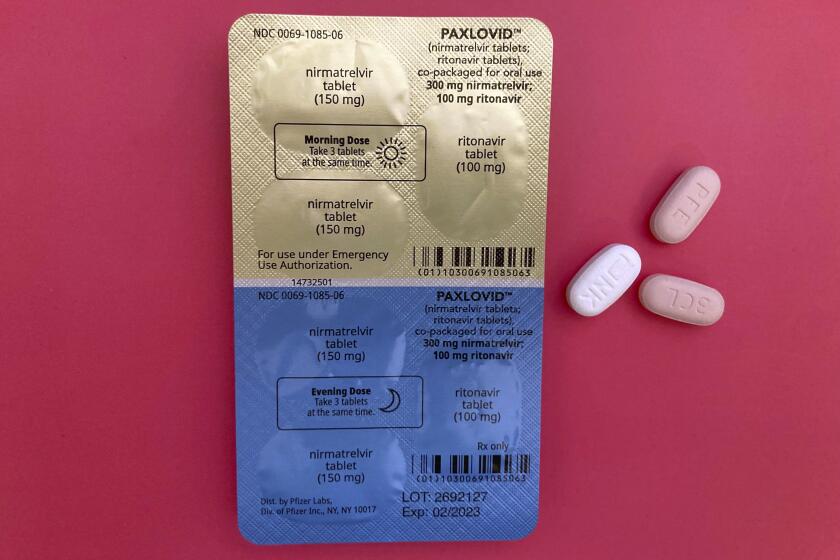

California lawmakers also have passed legislation requiring health plans and insurers to cover anti-COVID drugs.

Los Angeles County still has a COVID-19 emergency declaration in place, but discussion is underway to wind that down, perhaps by the end of March.

A pandemic allows the Food and Drug Administration to authorize vaccines and drugs for emergency use, even after the health emergency ends.

How will California respond moving forward?

A little more than a year ago, California officials unveiled their blueprint for the next phase of the pandemic response. They dubbed it the “SMARTER” plan — with the namesake acronym outlining an approach rooted in seven key areas: shots, masks, awareness, readiness, testing, education and Rx (or anti-COVID drugs).

The 30-page document includes a handful of specific preparedness goals officials say would well position the state to respond to the changing nature of COVID-19. Those include benchmarks regarding how many vaccines California should be equipped to administer daily and how many masks it should stockpile, as well as commitments to maintain robust testing capacity, wastewater surveillance and sequencing efforts — which together help officials track transmission trends and evolutionary changes of the coronavirus itself.

A new CDC report found that children under 5 are being vaccinated for COVID-19 at lower rates than older children.

The plan employs the analogy of a road trip to describe the shift in state thinking. At the start of the COVID-19 era, California was “driving on an unfamiliar road with low visibility, heavy rain, worn-down brakes and no windshield wipers.”

Now, “we are driving on a road that we have mostly driven before with good weather conditions, and in a car with new brakes and windshield wipers. There are still potential hazards on the road ahead, but we are much better equipped to anticipate and react to them.”

What are the current COVID-19 trends?

Case rates in California have hit another seasonal low: 55 for every 100,000 residents for the weekly period that ended Feb. 21. That’s similar to the seasonal lulls seen last September and October.

By contrast, the wintertime peak was 222 cases a week for every 100,000 residents. A weekly case rate of 100 or more is considered high.

As of Friday, there were 2,516 coronavirus-positive patients hospitalized in California. That’s substantially lower than the winter high of 4,648, logged on Jan. 3, but still higher than the low points seen the previous autumn, 1,514; or last spring, 949.

Statewide, 227 COVID-19 deaths were reported for the week ending Feb. 21 — a tally that pushed California’s cumulative COVID-19 death toll above 100,000. The winter high saw 407 COVID-19 deaths reported for the week that ended Jan. 17; and the prior autumn low was 102 deaths for the week that ended Nov. 29.

COVID-19 is expected to remain a significant cause of death for some time to come, especially among people who aren’t up-to-date on their vaccination and booster shots, and aren’t given anti-COVID drugs like Paxlovid when they do get infected.

About 60,000 U.S. residents have died from COVID-19 since October, a sum that’s more than triple the 18,000 estimated U.S. flu deaths over the same time period.

Another concern is long COVID — an array of symptoms that can persist for months or years after an acute coronavirus infection that is expected to result in a significant cause of disability in the U.S. for some time to come. A federal estimate, based on survey data, suggests 28% of people who have had COVID-19 have experienced long COVID.

Most people with long COVID experience improvements in symptoms over a long period of time, Ferrer said, but some people experience long COVID as a disability that has persisted for years and has not ended.

“It’s sobering to see how so many people are still affected by long COVID nearly three years into the pandemic,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.