It’s not the San Andreas, but fault system that produced 6.0 quake poses big dangers

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — The magnitude 6.0 earthquake that rattled parts of Northern California on Thursday caused no injuries and little damage. But it is a reminder that the Sierra Nevada area at the epicenter of the quake is seismically active and capable of a destructive temblor.

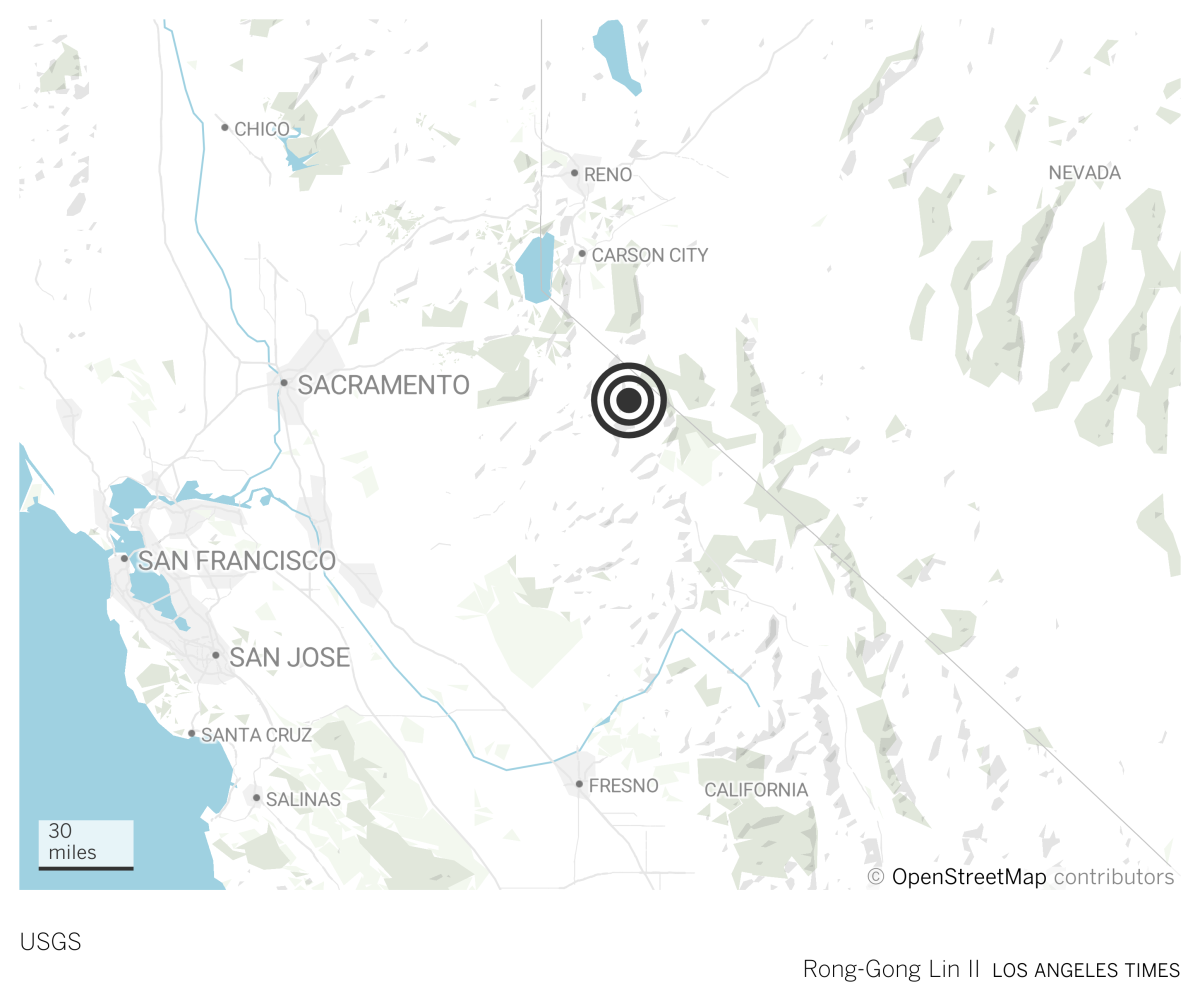

The earthquake, centered on the California-Nevada border, was felt as far west as San Francisco and as far south as Visalia, in the San Joaquin Valley. The epicenter was about 167 miles northeast of San Francisco, 125 miles northeast of Fresno, 110 miles east of Sacramento and 70 miles southeast of Reno.

While much of California’s earthquake risk has been historically focused on the San Andreas fault and places like Los Angeles and San Francisco, quakes are capable of causing significant destruction in the state’s Sierra Nevada and Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, as well as in neighboring Nevada.

Thursday’s earthquake occurred on the Antelope Valley fault system of the Eastern Sierra — unrelated to Los Angeles County’s Antelope Valley, 275 miles to the south. The fault is a small portion of the Sierra Nevada frontal bounding fault system, which creates the dramatic landscape drivers see when traveling on U.S. 395 on the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada, in places such as the Owens Valley, Bishop, Mammoth Lakes and June Lake.

“This was a small earthquake along essentially that whole fault system, and that’s a very active structure,” Austin Elliott, a U.S. Geological Survey research geologist, said at a news briefing Thursday.

One of California’s most powerful quakes on record was in the eastern Sierra Nevada, where the magnitude 7.4 Owens Valley earthquake at Lone Pine in 1872 resulted in the deaths of 27 people and destroyed the main buildings in almost every town in Inyo County.

The Reno area has an earthquake risk approaching that of San Francisco. Faults in the basin Reno sits in are capable of generating earthquakes as big as magnitude 6.8, and a larger fault in the Carson Valley just south of Reno could generate a quake as large as magnitude 7.4, according to the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology.

And UCLA experts warned in 2014 that a major earthquake sending destructive shaking to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta could potentially destroy aging levees, causing flooding and drawing in saline water from San Francisco Bay — which would contaminate one of the state’s key water supply systems.

Before we can prepare for the Big One, we have to know what “one” is. Here’s a basic primer on the science of earthquakes.

Thursday’s earthquake was the largest in the region since the magnitude 6.1 Double Spring Flat earthquake in 1994 in sparsely populated western Nevada, which was felt from Sacramento to Elko, Nev., but did not result in loss of life.

There have been a couple of dozen earthquakes larger than magnitude 5 in the region of Thursday’s quake in the last 50 years. It’s expected for a quake of this magnitude to be felt broadly across the state, Elliott said.

People living on top of basin sediments and soft soils are at higher risk of feeling amplified shaking from a distant quake, whereas people living on bedrock, a hillside or a ridge are less likely to feel it.

Elliott, who was in San Francisco when Thursday’s quake hit, said he felt strong shaking. “This made our apartment sway like wild. Really dizzying. Dog ran around a bit,” he wrote on Twitter.

Living on a relatively high floor of a building in San Francisco “may have certainly amplified the experience — compared to neighbors and other friends around me who did not feel the earthquake,” Elliott said during the news briefing.

For people in the Bay Area, “this one — because of its distance — was probably more perceptible in places that really amplify the slow, distant waves — and so, like the high building that I’m in,” he said.

But in places such as Reno or Carson City, Nev., “this was a much stronger jolt through there. And it got more than a jolt. It was probably a fairly good shake that was pretty alarming,” Elliott said.

The Eastern Sierra has long been a spot where geologists go to study the active earthquake faults that give the Sierra Nevada — California’s mightiest mountain range — its dramatic topography.

There are a number of active faults there in what’s called the Walker Lane system, said Keith Knudsen, deputy director of the USGS Earthquake Science Center in Menlo Park.

These are some of the major earthquake risks facing California

“There is tectonic slip that goes up the east side of the Sierra, and there have been a number of historical earthquakes of this size or bigger in the last few decades. So it’s not a big surprise that it happened here,” Knudsen said.

The Sierra Nevada is underlain by cold, hard rock, and the mountains “ring like a bell when an earthquake happens there,” he said. “So they transmit the earthquake energy really well” — which may explain why the quake was felt so widely across California.

Lin reported from San Francisco and Miller from Los Angeles. Times staff writers John Myers and Anita Chabria in Sacramento contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.