How the over-tapped Colorado River reached its current dire state

- Share via

Good morning, and welcome to the Essential California newsletter. It’s Friday, Feb. 10.

If you’ve just started following the contentious politics surrounding the Colorado River, it might seem like conflict is suddenly erupting.

But the crisis has been a long time in the making. I’m Ian James, a reporter on the Times’ Climate and Environment team, and in case you missed it, we recently published a series titled Colorado River in Crisis.

We set out to examine how the river’s worsening water deficit will affect the region. Our reporting took us on journeys from the Rocky Mountains to Mexico. We saw stark scenes of a river system at risk of collapse and heard a variety of perspectives on how the impending water reckoning could reshape the landscape across the Southwest.

How did we get to this pivotal moment?

There is a long history of wrangling over the river’s water among the seven states in the Colorado River Basin, going back to the signing of a landmark 1922 compact, as my colleague Michael Hiltzik details in a column this week. Among the notable dates is an incident in 1934 when Arizona dispatched a squad of National Guard troops to the river, as well as the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1963 decision in a long-running dispute between Arizona and California.

The Colorado has long been overallocated, with so much water diverted to supply farmlands and cities that the river’s delta in Mexico largely dried up decades ago, leaving only small fragments of its once-vast wetlands in the desert.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, scientists were already warning that overuse combined with the effects of climate change would likely drain the river’s major reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, to dangerously low levels.

Since 2000, the watershed has been ravaged by the one of the most severe droughts in centuries, one that research shows has been intensified by the heating of the planet.

In the 2010s, representatives of states and water agencies negotiated agreements to reduce water use. They met in 2019 on a terrace overlooking Hoover Dam and signed a set of deals called the Drought Contingency Plan, calling it a major step forward.

In recent years, leaders of Native tribes have pushed for inclusion and sought to be heard in talks on addressing the water shortage. Indigenous leaders have called for changes in how the river is managed, and some tribes have participated in voluntary water reductions.

But those and other reductions under the agreements between the states haven’t been nearly enough, and the reservoirs have continued dropping.

Why are states at odds on how to address the river’s shortfall?

Last year, federal water managers began calling for major water reductions to protect reservoir levels and prevent a collapse in water supplies. Their target: 2 million to 4 million acre-feet per year, a decrease of roughly 15% to 30%.

The federal Bureau of Reclamation and Interior Department announced in October that they were starting an expedited review to revise the rules for dealing with shortages. Officials are considering options to reduce the risk of Lake Mead dropping to “dead pool” levels — a point where no water could pass through the dam.

Federal officials urged the seven states and managers of water agencies to talk among themselves and deliver a proposal for handling cutbacks by the end of January.

Six of the seven states together submitted a proposal for how the cuts could be divided. California disagreed on that approach and submitted its own proposal.

At the center of the dispute is a proposal to start counting the water lost to evaporation from reservoirs and along the river. Such a change in the river’s Lower Basin would mean especially large cuts for California, which uses the single largest share of the river.

As my colleague Sean Greene and I reported, the feds must now consider two substantially different proposals, alongside any other measures they decide are necessary. The differences might not be insurmountable. And representatives of the states are continuing to negotiate in private.

But there’s also the potential for the dispute to devolve into litigation. My colleague Hayley Smith and I wrote about how some water managers are concerned that strict adherence to the water-rights priority system under the legal framework known as the Law of the River is getting in the way of a solution.

Others, including Imperial Valley farmer John Hawk, have strongly opposed what they call attempts to undermine the legal system governing water use. Hawk said he’s concerned that by rewriting the rules, “they want to hammer away at priority users.”

What lies ahead in efforts to adapt?

All the current wrangling focuses on the immediate need to address the water deficit over the next four years. The states still need to negotiate new rules for sharing shortages in the longer term. The current guidelines expire at the end of 2026.

That means the struggle to collectively adapt to the shrinking Colorado River isn’t going away anytime soon. As my colleague Rong-Gong Lin II and I reported, scientists and water managers say the region will need to plan for low reservoir levels for years to come.

At this point, the entire region faces a water reckoning. The need to shrink water use will probably result in less water flowing to farms, more water restrictions for residents and fewer green lawns. It’s also bringing calls to limit suburban growth and shift away from thirsty cattle-feed crops like alfalfa.

David Pierce, a climate scientist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, pointed out that roughly 80% of the river’s water goes to agriculture under a system established generations ago.

“Fundamentally, the seeds of this current situation were planted decades ago when the U.S. decided to irrigate a desert with Colorado River water,” Pierce told me in an email. “The system was carefully calibrated to just break even in the absence of climate change. Climate change is that last push on water availability that throws the whole system off.”

You can find all the stories in our Colorado River series on this page, together with graphics, videos and a special six-part podcast series.

And if you have thoughts you’d like to share on water issues in California and the West, we’d like to hear from you. You can email me or, if you’d like to share your perspective publicly, here is how to submit a letter to the editor to the Times for publication.

And now, here’s what’s happening across California, from Ryan Fonseca:

Note: Some of the sites we link to may limit the number of stories you can access without subscribing.

Check out "The Times" podcast for essential news and more

These days, waking up to current events can be, well, daunting. If you’re seeking a more balanced news diet, “The Times” podcast is for you. Gustavo Arellano, along with a diverse set of reporters from the award-winning L.A. Times newsroom, delivers the most interesting stories from the Los Angeles Times every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Listen and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT

The Internal Revenue Service says Californians should wait to file their 2022 tax returns as the agency decides if it will collect taxes on California’s “Middle Class Tax Refund.” But the open-ended delay puts eagerly awaiting tax refunds on hold. That’s especially troubling to some families expecting their Earned Income Credit and Child Tax Credits. Los Angeles Times

With eggs so scarce and so expensive, some Californians are turning into smugglers. Border Patrol agents in San Diego report an increase in the number of people trying to illegally bring eggs across the border from Mexico. Officials cite the risk of spreading bird flu and Newcastle disease, which can spread through unwashed egg shells and soiled containers. Los Angeles Times

Should drivers of large trucks and SUVs pay more to operate their bigger, heavier vehicles? A new Assembly bill wants state transportation officials to study the impacts of imposing a weight fee to fund street safety improvement projects. The bill also calls for an “analysis of the relationship between vehicle weight and vulnerable road user injuries and fatalities.” San Francisco Chronicle

CRIME, COURTS AND POLICING

Newly elected City Controller Kenneth Mejia has vowed to scrutinize how L.A.’s police department spends its money. The city auditor and some of his staff recently attended a local protest against the police killing of Tyre Nichols in Memphis to observe the response and behavior of officers. That didn’t sit well with the police union, which issued a statement claiming Mejia and “his cadre of staff and advisors hate cops.” LAist

Prosecutors in Ventura County have charged an Oxnard man with the 1981 murders of two young women. Authorities said DNA analysis via “genetic genealogy” helped investigators crack the 41-year-old cold case. Tony Garcia, 68, is accused of killing 20-year-old Camarillo resident Rachel Zendejas and 21-year-old Oxnard resident Lisa Gondek. Ventura County Star

Support our journalism

HEALTH AND THE ENVIRONMENT

A pandemic-triggered increase in federal aid allowed California to issue higher-than-usual amounts in food stamps, but that’s set to end in April. Food bank officials fear the cutback in CalFresh funds — along with inflation driving up prices — will lead to a hunger spike. CalMatters

Nearly 5 million bottles of Fabuloso Multi-Purpose Cleaner have been recalled because of bacteria exposure. The bacteria is especially risky for “people with weakened immune systems, external medical devices, or underlying lung conditions,” according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission. The majority of the affected bottles did not make to store shelves, but about 1 million bottles were released for sale at a variety of physical and online stores. Los Angeles Times

California’s war on natural gas is nothing new, but now the fight is on the national stage. Times energy reporter Sammy Roth examined the local skirmishes between Southern California Gas Co., residents and government — and what that indicates about the battles to come across the country. Los Angeles Times

CALIFORNIA CULTURE

A growing number of Californians and Golden State-based companies have been streaming into Nevada in recent years. “The migrants are seeking to re-create a California lifestyle,” my colleagues Noah Bierman and Don Lee write, “a technology hub with comfortable communities, economic growth and mountain views — without California’s problems.” But not everyone is happy about the influx. As more tech workers move in, workers in the hospitality industry — the backbone of Nevada’s economy — say they’re getting priced out. Los Angeles Times

Now’s a great time to visit Palm Springs before the Coachella Valley oven finishes pre-heating. Explore our intricate guide to where to stay, what to eat and how to have fun over a desert weekend. Los Angeles Times

Free online games

Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games in our new game center at latimes.com/games.

AND FINALLY

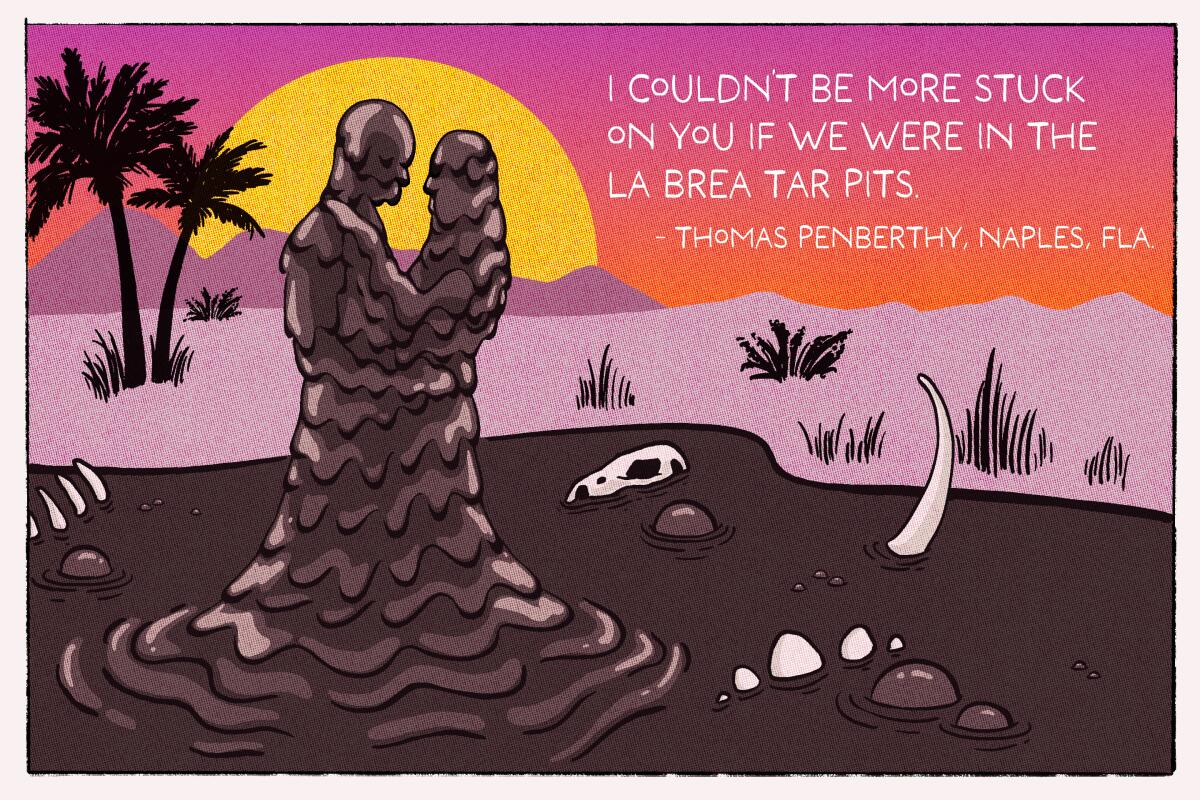

Some of you have been sending us your romantic California-themed Valentine’s prose, aka Calentines. We’re featuring the sappiest, wittiest submissions through Valentine’s Day, gussied up by our spectacular design team. Here’s the next installment:

There’s still plenty of time to share your California love. Submit your ideas here. Please keep submissions under 50 words.

Please let us know what we can do to make this newsletter more useful to you. Send comments to [email protected].

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.