Western megadrought is worst in 1,200 years, intensified by climate change, study finds

- Share via

The extreme dryness that has ravaged the American West for more than two decades now ranks as the driest 22-year period in at least 1,200 years, and scientists have found that this megadrought is being intensified by humanity’s heating of the planet.

In their research, the scientists examined major droughts in southwestern North America back to the year 800 and determined that the region’s desiccation so far this century has surpassed the severity of a megadrought in the late 1500s, making it the driest 22-year stretch on record. The authors of the study also concluded that dry conditions will likely continue through this year and, judging from the past, may persist for years.

The researchers found the current drought wouldn’t be nearly as severe without global warming. They estimated that 42% of the drought’s severity is attributable to higher temperatures caused by greenhouse gases accumulating in the atmosphere.

“The results are really concerning, because it’s showing that the drought conditions we are facing now are substantially worse because of climate change,” said Park Williams, a climate scientist at UCLA and the study’s lead author. “But that also there is quite a bit of room for drought conditions to get worse.”

Williams and his colleagues compared the current drought to seven other megadroughts between the 800s and 1500s that lasted between 23 years and 30 years.

They used ancient records of these droughts captured in the growth rings of trees.

Wood cores extracted from thousands of trees enabled the scientists to reconstruct the soil moisture centuries ago. They used data from trees at about 1,600 sites across the region, from Montana to California to northern Mexico.

The study, which was published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, adds to a growing body of research that shows the American West faces major challenges as the burning of fossil fuels continues to push temperatures higher, intensifying the drying trend.

To water resiliency advocates at the U.N. climate conference, the Colorado River stands out as ‘the best example globally of how things can go badly.’

Williams was part of a team that published a similar study in 2020. At the time, they found the drought since 2000 was the second-worst after the late 1500s megadrought. With widespread heat and dryness over the past two years, the current drought has passed that extreme mark.

Some scientists describe the trend in the West as “aridification” and say the region must prepare for the drying to continue as temperatures continue to climb.

Williams said the West is prone to extreme variability from dry periods to wet periods, like a yo-yo going up and down, but these variations are now “superimposed on a serious drying trend” with climate change.

“The dice have been loaded so heavily toward drying,” he said.

The average temperature in southwestern North America since 2000 has been 1.6 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the average during the previous 50 years, the researchers said. The warmer temperatures have compounded the drought by increasing evaporation, drying soils and leaving less water flowing in streams and rivers.

Higher temperatures make the atmosphere thirstier, drying out soil and vegetation in much the same way that “our house plants dry out when we turn on the heater,” Williams said.

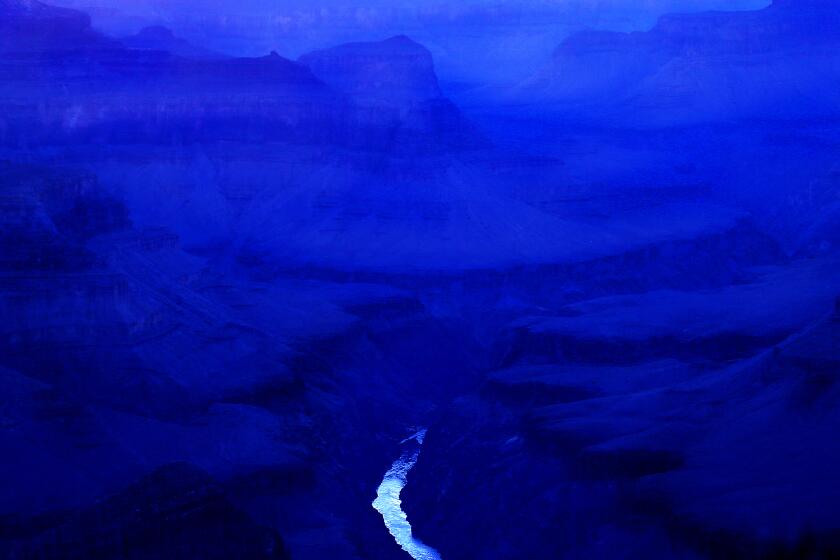

The scientists pointed out that the flow of the Colorado River during the 2020 and 2021 water years shrank to the lowest two-year average in more than a century of recordkeeping.

The river supplies water across seven states, from Wyoming to California, and to northern Mexico. But it has been chronically overused, and the drought has compounded the problems. Over the past year, its two largest reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, declined to their lowest levels on record.

“We need to understand that the water budget of the West is changing beneath our feet rapidly,” Williams said. “We need to be prepared for a much drier future and to not rely so much on hope that when it gets wet again, we can just go back to business-as-usual water management.”

The hot, dry years have taken a major toll on water supplies and landscapes throughout California and the West. California’s reservoirs have dropped during the past two years. In Utah, the Great Salt Lake has declined to record-low levels. Extreme heat has contributed to explosive wildfires. And in the Mojave Desert, scientists have attributed major declines in bird populations to hotter, drier conditions brought on by climate change.

New study says climate change is essentially two-thirds to 88% responsible for the conditions driving wildfire woes in the western United States.

Even without climate change, the past two decades would have been a “bad luck period” naturally for the region, Williams said. But without the influence of climate change, he said, “this drought wouldn’t even be coming close to matching the worst of the megadroughts.”

Some of the long droughts included those from 1213 to 1237 and from 1271 to 1300. During that century, the Indigenous people who lived and farmed in villages in the Four Corners region are thought to have left their cliffside homes because of drought.

The scientists studied data compiled over decades by hundreds of other researchers, who extracted wood cores by boring into long-lived trees such as Douglas firs, piñon pines, ponderosa pines and blue oaks.

They found the current drought has included two years — 2002 and 2021 — that rank among the driest in the past 1,200 years. And with the surge in drying over the past year, Williams said, these 22 years have already been drier on average than most of the longer megadroughts.

The late 1500s drought ended abruptly after 23 years when wet conditions swept across the region. But the current drought shows no signs of subsiding.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor website, 96% of the Western U.S. is now abnormally dry or worse, and 88% of the region is in drought.

The drought in the western United States is putting California’s reservoirs at dangerously low levels.

The scientists projected it’s highly likely the drought will continue at least through this year. They considered a hypothetical future scenario based on soil moisture during all 40-year periods in the past 1,200 years and then superimposed the same amount of climate change-driven drying that has occurred in recent years. They found that in 94% of their simulations, the drought continued for at least a 23rd year. And in 75% of the simulations, the drought lasted 30 years.

“When it’s in a very depleted state, it takes a long time to fill the bucket back up,” Williams said. “It would take exceptional luck to end this drought in the next few years. There’s only been a couple of examples of that type of luck in the last 1,200 years of data that we have.”

Williams coauthored the study with researchers Benjamin Cook and Jason Smerdon of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. They used 29 climate models to estimate the influence of higher temperatures unleashed by climate change.

When they analyzed how the drought would have evolved without climate change, they found that the region would have emerged from drought during wet years in 2005 and 2006, and then drought would have set in again in 2007, Williams said.

The scientists used a 10-year running average in assessing long-term trends, so a single wet year, such as 2019, wasn’t enough to end the run of mostly parched years.

The research focused on the entire region, but there were differences depending on the area. While the dryness has been most extreme in areas from Arizona to the Rocky Mountains, the study showed that much of California experienced one of the driest 22-year periods, though not the absolute driest.

Williams said the research should serve as a warning that the drying could get much worse in the years and decades to come.

“The big megadroughts that occurred last millennium occurred in the absence of climate change,” Williams said. When such megadroughts return, they’ll be occurring “in a world where the atmosphere is also artificially warmer because of human-caused climate change, which would be absolutely catastrophic.”

Isla Simpson, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who wasn’t involved in the study, said she thinks the methods are solid and the findings make an important contribution to previous science.

“It’s really useful to have this update, given how severe the last two years have been,” Simpson said.

She said the current drought has occurred in part due to low precipitation, but it’s really the effect of higher temperatures that has worsened the drying and is “very clear climate change signal.”

Despite a California law intended to end over-pumping of aquifers, a frenzy of agricultural well drilling continues in the San Joaquin Valley.

“We have emerged out of the climate of the 20th century in terms of temperature, which will have an impact on evaporation and soil moisture,” Simpson said. There will still be the natural swings from dry to wet, she added, “but we’re experiencing this variability now within this long-term aridification due to anthropogenic climate change, which is going to make the events more severe.”

Williams said the research points to real problems in the chronic overuse of water sources like the Colorado River, which fueled the growth of cities from Los Angeles to Phoenix over the past century. He said the widespread depletion of groundwater is another symptom of overdrawing the region’s critical water reserves.

Many people in the West may not feel like they’re living through a megadrought, he said, because “we have all of these buffers in our system now, like groundwater and large reservoirs.”

“But we are utilizing those backstops so rapidly right now that we’re at real risk of those backstops not being there for us in 10 or 20 years,” he said, “when either this event still hasn’t ended, or when the next megadrought has already begun.”