Did CIA torture yield key information? Report says no; defenders disagree

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — Did torture make America safer? The conclusion of a Senate committee that investigated CIA interrogation of terrorism suspects is that it did not — that intelligence gained under duress stopped no imminent plots. But that is hotly disputed by current and former CIA officials, former members of the George W. Bush White House and some Republican senators.

The exhaustive report by the Senate Intelligence Committee released Tuesday undermines or disproves major CIA claims of success, including some that dominated headlines and frightened Americans a decade ago.

The report cites internal CIA documents that show the key intelligence either came from other sources, was obtained before the individual was tortured, or was based on bogus threats.

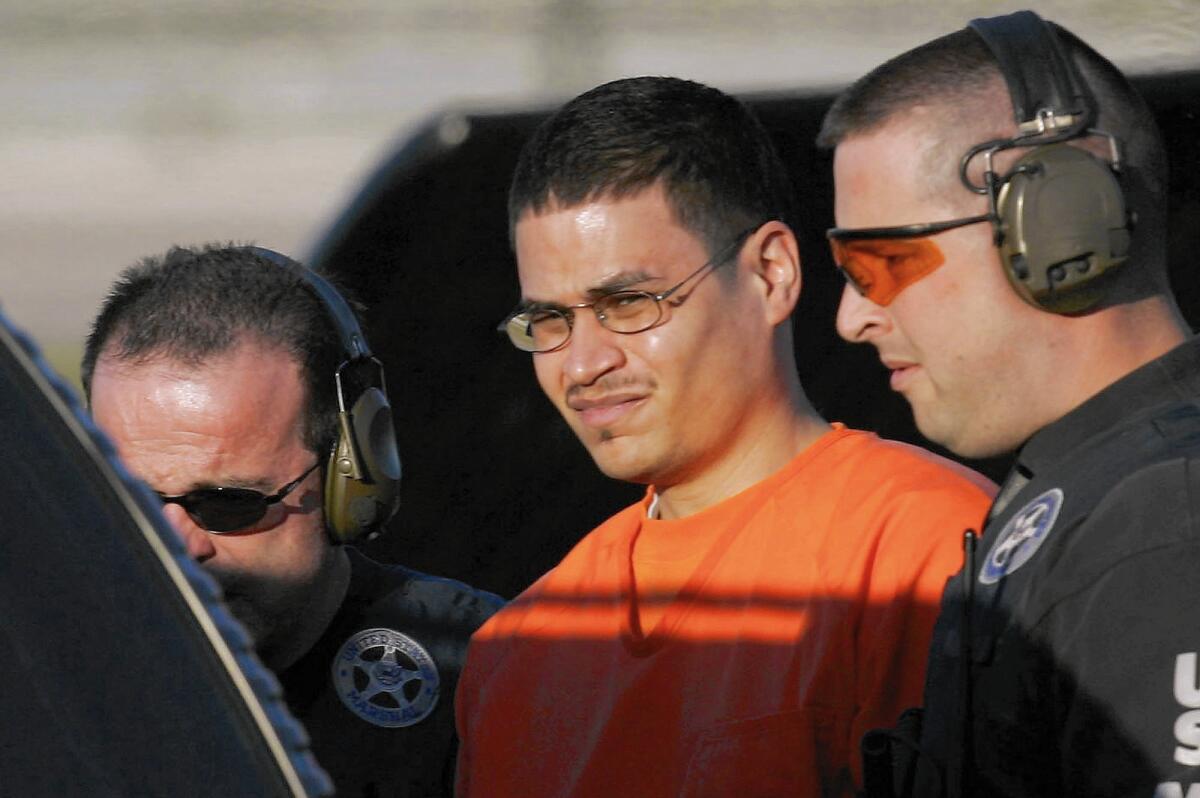

In May 2002, for example, senior Bush aides announced they had disrupted a deadly radiological “dirty bomb” plot by Jose Padilla, a former Chicago gang member who had gone to Afghanistan.

After Padilla’s arrest, administration officials publicly credited the CIA’s interrogations of Al Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah for disrupting the dirty bomb plot.

But Padilla was arrested three months before Zubaydah was subjected to 17 straight days of waterboarding and other painful practices. Padilla ultimately was convicted in a civilian court of terrorism-related charges but was never charged with a dirty bomb plot.

In 2005, the head of the agency’s chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear group mocked what he called CIA “lore” that it had stopped Padilla from building a dirty bomb.

“Anyone who believes you can build a [radiological dispersion device] by ‘putting uranium in buckets and spinning them clockwise over your head to separate the uranium’ is not going to advance al-Qa’ida’s nuclear capabilities,” he wrote, according to a memo cited in the Senate report.

In 2006, President Bush similarly credited the CIA interrogations for helping to foil a terrorist attack on the U.S. Consulate and other Western targets in Karachi, Pakistan. Agency officials said they had obtained the details from Ammar al Baluchi and Walid bin Attash, two Al Qaeda figures held at secret CIA prisons.

But the Senate report says the two operatives had revealed the plot weeks earlier to Pakistani officials, who had passed it to the CIA, leading the consulate to beef up security. In internal cables, CIA officials acknowledged they knew about the danger before the two repeated the details under torture.

In 2006, the White House also announced that Al Qaeda had planned to launch a “second wave” attack on the West Coast after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, including crashing a plane into the former Library Tower in downtown Los Angeles. The CIA said Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who was waterboarded 183 times in one month, had revealed the plot.

But the Senate report says the CIA had learned about it much earlier, in January 2002, after arresting a Malaysian member of Al Qaeda. Mohammed simply confirmed it after he was tortured, investigators found.

The CIA also claimed credit in 2003, when the Justice Department charged Iyman Faris, a Pakistani American in Ohio, with a plot to destroy the Brooklyn Bridge by cutting its suspension cables with blowtorches. The CIA repeatedly said it had learned of the plot from waterboarding Mohammed.

That is misleading at best. The report says a court-approved wiretap of another American, Majid Khan, prompted the FBI to investigate Faris.

When confronted, he acknowledged meeting Mohammed but said he had decided the plan to destroy U.S. bridges was unfeasible and therefore not a threat. Court papers show he subsequently worked as a double agent for the FBI and later pleaded guilty to separate terrorism charges.

The CIA also said that after waterboarding, Mohammed had revealed a plan to hijack aircraft to crash into London’s Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf commercial district.

The report says the CIA knew about the plot months before Mohammed was captured, however. In internal cables, the CIA deemed the plot “not imminent” because Al Qaeda couldn’t find pilots to take on the suicide mission.

Perhaps most critically, the Senate report challenges the CIA’s claims that its use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” played a key role in identifying Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, the courier who ultimately led the CIA to Osama bin Laden’s hide-out in Pakistan.

The report says an Al Qaeda operative named Hassan Ghul described the courier as Bin Laden’s “closest assistant” after Ghul’s arrest in 2004, but before he was subjected to CIA torture.

“He sang like a Tweety Bird,” a CIA officer told the CIA inspector general about Ghul’s initial questioning. “He opened up right away and was cooperative from the outset.”

Despite his apparent cooperation, Ghul was transferred to a secret CIA prison where he was “shaved, barbered, stripped and placed in the standing position against the wall” and forced to stay awake for 59 hours.

The Senate report states Ghul, who suffered hallucinations and heart palpitations, provided no “other information of substance” after his torture.

Former CIA officials and some Republicans dispute that narrative. They say that after Ghul was sleep deprived and humiliated, he provided more detail about a specific message the courier delivered for Bin Laden to Al Qaeda operations chief Abu Faraj al-Libi.

A detainee at a different CIA prison first mentioned the name of Bin Laden’s courier and a possible connection to Libi during a “period of enhanced interrogation,” according to the rebuttal of the Senate report’s claims by Republicans on the intelligence committee.

The minority report also says Mohammed and two other high-ranking Al Qaeda operatives subjected to brutal treatment had denied knowing the courier. That was a “clear sign” to CIA analysts that the detainees had “something to hide,” tipping them off to the courier’s “true importance,” according to the rebuttal.

Critics also said the Senate report went too far in claiming that intelligence gained under torture could have been obtained through other sources or technical means.

“It’s impossible to know in hindsight” if non-coercive interrogations could have obtained the same intelligence, the CIA said in a statement.

“The answer to this question is and will forever remain unknowable,” CIA Director John Brennan said in a separate statement. Claims that harsh interrogations produced no unique intelligence that disrupted terrorist plots are “wrong,” he said.

In internal assessments, the CIA concluded in 2004 and 2005 that the interrogations had helped thwart plots. But the Senate study says the evaluations did not check whether critical intelligence was obtained before or after harsh methods were used.

Committee investigators reviewed 6.3 million pages of internal CIA emails, reports, memos and other documents in assembling the report. They did not interview CIA officers involved because of an ongoing Justice Department investigation. Critics have seized on the failure to conduct interviews to argue that the report is one-sided and incomplete.

Sen. Susan Collins of Maine was one of three Republicans who voted to declassify the executive summary released Tuesday, part of a 6,700-page report that remains classified.

Whether the waterboarding and other harsh techniques were effective is not the point, she argued. “Torture need not be ineffective to be wrong,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.