Guatemala President Otto Perez Molina resigns in face of arrest warrant

- Share via

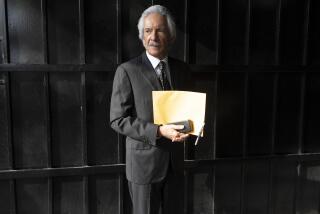

Reporting from Mexico City — Guatemalan legislators Thursday accepted the resignation of President Otto Perez Molina, who this week lost his immunity from prosecution and saw an arrest warrant issued for him in connection with a corruption scandal.

Perez Molina, who had said he would not resign, changed his position after the nation’s prosecutor announced late Wednesday that a warrant had been issued for his arrest. Congress had voted on Tuesday to strip the president of his immunity from prosecution.

In a letter presented to Congress about an hour after the arrest warrant was issued, Perez Molina announced that he was stepping down “in the interest of the country,” according to his spokesman. After a court hearing, Perez Molina was placed in custody.

Vice President Alejandro Maldonado becomes interim president as Guatemalans prepare to go to the polls for national elections Sunday. Maldonado became vice president after his predecessor, Roxana Baldetti, who is in jail facing charges in the same scandal, resigned in May.

Perez Molina’s term as president would have ended in January because of term limits. He and Baldetti have denied being involved in the scandal, which prosecutors say involved officials in the customs department receiving kickbacks in return for reducing import taxes for companies.

The investigation of the scheme was a joint effort by the attorney general’s office and the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, known as the CICIG, an independent body set up by the United Nations almost a decade ago.

Atty. Gen. Thelma Aldana said Thursday via Twitter that the Guatemalan people are adamant that everyone should face the same justice process. On Wednesday, she had told reporters that Perez Molina faced “charges of fraud, illicit association and corruption.”

“This sends a very strong and very clear message to those who are wanting a change, a different form of government, that it can happen,” said Adriana Beltran, senior associate for citizen security at the Washington Office for Latin America, a nonprofit organization.

Corruption has been one of the biggest impediments to economic growth and development for several countries in the region, analysts said.

Some analysts pointed to the establishment of the international commission as a game-changer in Guatemala’s fight against corruption, and a few nations in the region have called for their own versions of it.

This year, protests erupted in Honduras over a social security embezzlement scandal, prompting calls for the establishment of a body similar to the one in Guatemala to help strengthen the country’s institutions and justice systems.

Arturo Alvarado, an independent consultant and former Honduran finance minister, said in an email Thursday, “For the structural changes to happen we need a CICIG in Honduras or a similar international institution, because those who benefit from the status quo aren’t going to change things.”

Administrations in El Salvador have also floated the idea.

But it took Guatemala’s CICIG years to get where it is today and couldn’t have done so without the cooperation of local institutions as well as the protest movement that pushed for change, said Pedro Trujillo, director of the political science department at Francisco Marquis University in Guatemala City.

Eric L. Olson, associate director of the Latin American Program at the Wilson Center, a Washington Research Institute, said a body like the CICIG doesn’t offer a one-size-fits-all solution.

“What happens in Latin American countries confronted by huge problems of crime and violence is that they don’t deal with it by enabling the justice system to function appropriately,” Olson said. “They deal with it by focusing on confrontations with criminal groups, prison and incarceration etc., but they never deal with the underlying problem of corruption and weak state institutions, and that’s really what’s at the heart of it.

“It’s not so much that every country needs a CICIG; it’s that they need an independent, capable, honest attorney general’s office that can resist pressures,” Olson said. “That to me is the key here.”

Lorenzo Meyer, a prominent Mexican historian, said Guatemala’s effort to fight corruption was enviable.

“Here we have the same problems, worse even,” he said, “and we can find no way out.”

Bonello is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.