Arab women stretch limits

- Share via

Another in a series of occasional articles.

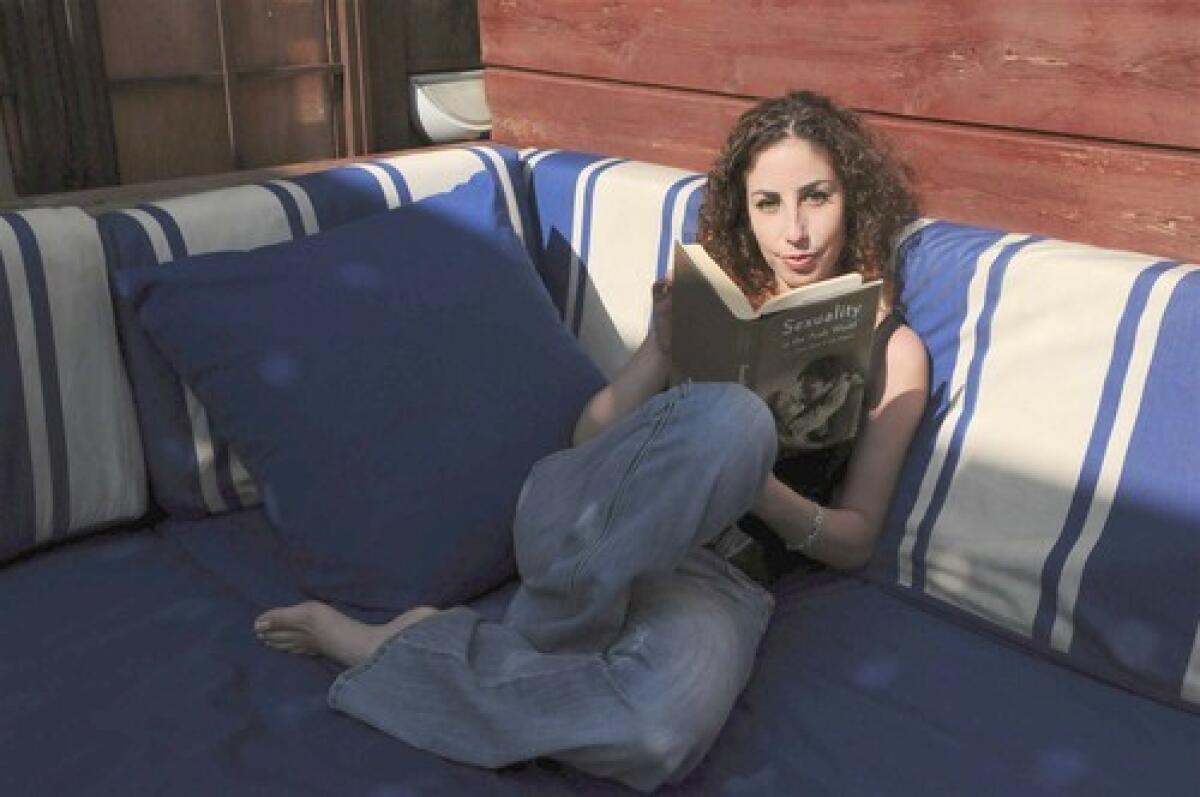

BEIRUT -- The censors didn’t quite know what to do with Lina Khoury’s play about sex, rape, menopause and a visit to the gynecologist, but Islamic hard-liners were pretty specific: One wanted to stone the 32-year-old writer; others accused her of being an Israeli agent planting immoral ideas in the Arab world.

The characters in “Women’s Talk” share secrets only uttered when men aren’t around. Riffs on pubic hairstyles and sexual desires may be a predictable story line in Hollywood, but here Western-influenced portrayals of women in the arts are condemned by clerics and conservatives as devil-inspired liberalism.

Khoury and her sharp-tongued alter egos are part of a coterie of real-life and fictional women across the Middle East who are pushing boundaries as political talk-show hosts, hip-hop divas, war correspondents, a defiantly divorced columnist and characters such as Vola, the red-haired eccentric of the Lebanese film “The Bus” who slips into an affair without any care of what society thinks.

They are at once liberated and repressed, devout and rebellious. Borrowing from Oprah Winfrey, Beyonce and even Hillary Rodham Clinton, they move between tribal and Islamic customs and media markets that are often layered in sexual innuendo.

In Saudi Arabia, women cannot drive or vote, glimpsing equality only during vacations away from the kingdom. But many women in Islamic countries long ago broke through the image of the black-veiled wife peeking from behind courtyard walls. Venture beyond the scrim of conservatism to the film studios of Lebanon, where the diva pose, seductively articulated by Haifa Wehbe, a Shiite Muslim model-actress-singer, is calculated down to the curl of an eyelash.

The crosscurrent of cultures is apparent in Khoury’s “Women’s Talk,” a Middle East version of the Broadway play “The Vagina Monologues” that has turned the diarist into an unwitting Dr. Ruth for women who wear low-cut blouses and slit skirts and also for those draped in niqabs, or face veils, and abayas.

“In the Arab world, I’ve suddenly become an expert on women and sexuality. It’s insane, hilarious. I write plays. I’m not a therapist,” said Khoury, whose play closed in February after a two-year run. “Some men are saying that I’m breaking the rules of society and religion. . . . Sexuality and women’s freedoms are threatening to men. Some actresses I wanted for the parts wouldn’t take them. They were scared of what their husbands or boyfriends would say.”

Tempering Western attitudes with Muslim sensibilities becomes a question of how far to push the Middle East’s patriarchal societies. This is still a region, after all, where in some countries a wife can be stoned for committing adultery and women make up 9% of lawmakers in Arab parliaments and 33% of the workforce, the lowest percentage in the world.

The candor in Khoury’s play is comical and acerbic; one character says her parents would handle an Israeli invasion of Lebanon better than news of her divorce. A more salacious take on women’s rights and sexual freedom is Beirut’s music-video market that beams seduction into Arab living rooms.

The tension underlying both sides can be spotted on this city’s streets where posters of Kalashnikov assault rifles and martyrs for the militant group Hezbollah peek out amid billboards of women who appear as though they’ve slipped off the pages of Vanity Fair.

“The sexy look in Beirut is provocative and plastic,” said Khoury, who was born into a Christian family during Lebanon’s civil conflict in the 1980s. “It all grows out of a restricted society of sexual repression. And when this freedom finally does come out, it comes out very dramatically in a concentrated, almost pornographic look.”

Out of the shadow

But if you turn off the “bimbos, you see a lot of positive women role models in the media,” said Dima Dabbous-Sensenig, head of the Institute for Women’s Studies in the Arab World at Lebanese American University in Beirut. “Lebanon’s July 2006 war with Israel was covered by women television correspondents in their 20s. They were going everywhere. They were braver than men.”

Women have become important opinion makers in news and talk shows that borrow heavily from Western programming. In 2003, the Algerian newscaster Khadija Ben Ganna became the first anchor on Al Jazeera to wear the hijab on air, a gesture denounced by secularists as a symbol of Islamic revival. In Cairo, the unveiled Mona El Shazly has risen in the ratings with “Ten O’Clock,” a show that asks tough questions on politics, social unrest and other sensitive topics.

The cultural terrain between the veil and free-flowing hair has led to contentious debate within Islam over virtue and image. Many Muslim women choose to wear the hijab as an emblem of their religion, a sign of humility to God. Others regard it a fashion accouterment. But growing Islamic devotion in countries such as Egypt has led to an increase in the number of women wearing hijabs, and those who don’t often feel societal and family pressures.

An illustration of this dilemma is the cover of Amy Mowafi’s new book, “Fe-Mail: The Trials and Tribulations of Being a Good Egyptian Girl,” which features a drawing of an unveiled woman in stiletto boots with a halo and a devil’s tail. An editor and columnist in Cairo, Mowafi is the Muslim version of the Carrie Bradshaw character in “Sex and the City.” Mowafi is not as explicit as the TV show’s foursome in New York, but she is unabashed as she stumbles, if not in Manolo Blahniks, “along that precarious line between East and West.”

She writes: “And so now I find myself a divorcee, with that big dramatic D word marked upon my forehead. I find myself stranded in this sort of weird wasteland between virgin and whore. I was married, I’ve obviously been there and done ‘it’ and enough times to have had the innocence which Arab men so desperately crave thoroughly wiped away . . . or sullied . . . or whatever.”

‘Good girl syndrome’

The daughter of an Egyptian investment banker and businesswoman, Mowafi was raised in a moderately religious home in England. Her 2002 move to Egypt, where she writes for the lifestyle magazine Enigma, led her to an Islamic society of nosy doormen, evangelical preachers and encounters with men who proclaimed to be pious but used professional meetings as a chance to flirt. In Britain, she could date and not worry about where it would lead; in Cairo, the rules were different.

“We’re out on a date and it’s fun, but is he going to marry me? I’m in Egypt. I’m a Muslim. He just can’t be my boyfriend,” Mowafi said the other day over coffee in a haunt that clicked with computers and the whispered buzz of young love.

“I don’t think Arab women will ever let go of this ‘good girl syndrome.’ We’re educated, we’re more ambitious,” she said, shifting to an extreme example of Western decadence, “but I’d never want to see an Arab woman splayed on the floor of a club with her legs wide open like in the West. I don’t think that’s a sign of modernity. No, we don’t want to be answerable to men, but we don’t want to lose our sense of morality either.”

What she notices these days is an increasing number of Middle Eastern women educated in the West returning to their countries with a progressiveness that threatens tradition. Khoury fits that description; she wrote “Women’s Talk” after getting a master of fine arts degree at the University of Arkansas. Mowafi said images of the liberal Arab woman are also spreading on blogs and Facebook, creating a two-track world in which the call to prayer lingers amid the latest hit from the Pussycat Dolls.

“You should see some of the comments I get on Facebook,” she said. “They are from girls in hijabs who have looked at my pictures and some of the things I’ve done, and said, ‘That looks like so much fun,’ or ‘Yes, I’ve always thought these same things.’

“Women like me can come back to invest our knowledge.”

Mowafi may be provocative on the page, but Nada Abou Farhat has been riling sensitivities on the screen for years. The 31-year-old Lebanese actress piqued the nation a decade ago when her character openly kissed her lover in a popular soap opera. More recently, her film character Vola was a sexually free Christian who fell in love with a Muslim. Vola earned her critical praise, but one kissing scene in “The Bus” was viewed as so wanton by Islamic standards that a conservative blogger sent it to a porn website.

“You have to laugh about something like that,” said Farhat, who sat on a recent rainy night in a Beirut cafe.

‘This is our revolution’

She spoke of the shades of different women she’s played, from an adulteress in “Betrayal” to a mother searching for her son during the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war in the film “Under the Bombs.” She was self-conscious about speaking English in an interview, but it was another challenge, and Farhat, who races through crooked streets in a red sports car, turned to an interpreter only when an occasional word was beyond reach.

“More and more scripts these days are being written by women,” she said. “We already know what you men think -- now it’s our turn.”

She paused, struggled with the precise meaning of a phrase, settled on an analogy.

“We are in a strange cultural chaos now, like a messy finger painting. Maybe women are seen as overreacting to make a point,” she said. “But we need to be vulgar. This is our revolution.”

The battle between religion and culture often turns into a game of euphemisms. In the play “Women’s Talk,” the censors, skilled mainly in excising political passages, were out of their element with gynecological terminology. Khoury had to submit the play to them five times for arguments over proposed revisions. She saved them a bit of consternation by changing the word “vagina” to the less threatening, made-up “coco.”

“ ‘Vagina’ translated in Arabic for me sounded too awkward,” Khoury said.

Her next play is about relationships and how they crash in a frenetic, modern world.

“Things are changing so fast, and all the rules we’ve been taught about relationships have no value,” Khoury said.

“There’s technology, economics, globalization, all these pressures on us. . . . It’s funny, but when I got back from the U.S., I didn’t wear a bra for a while. I felt liberated and I thought, why not be that way here? But you can’t really. A lot of guys were buying me drinks. They thought I was easy.”

--

Noha El-Hennawy of The Times’ Cairo Bureau and Raed Rafei of The Times’ Beirut Bureau contributed to this report.More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.