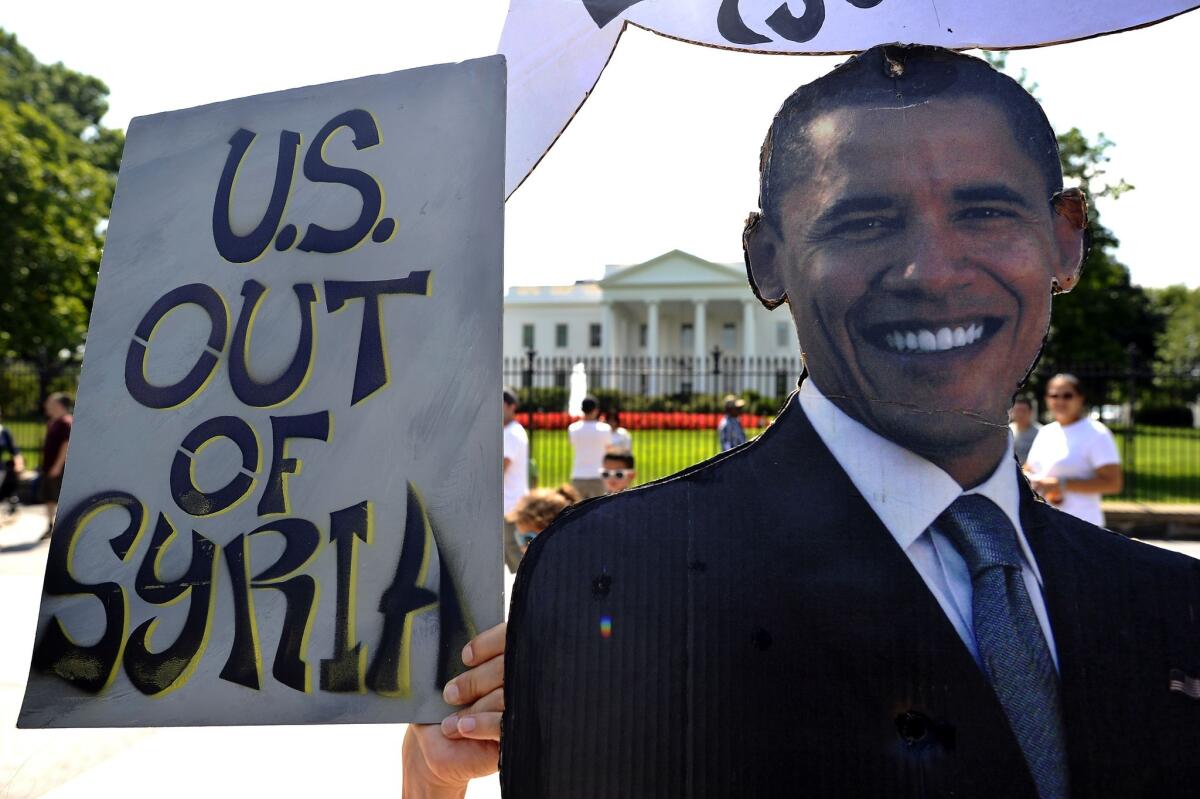

Obama at crossroads, largely alone

- Share via

WASHINGTON -- The head of the United Nations wants him to give peace a chance. His closest foreign ally backed away. Many in Congress, even in his own party, are wary.

Still, the president who was first elected to the White House by decrying wars of choice and promising to end military entanglements is on the verge of lunging into another one.

President Obama’s decision to lead the charge against the Syrian government for its suspected use of chemical weapons without first securing the support of a broad international coalition and a clear majority of the American public marks a striking moment of isolation for an outspoken advocate for international cooperation.

Nearly all previous presidents have faced pressure to react to humanitarian crises. But Obama has responded to allegations that the Syrian government was responsible for a poison gas attack that killed more than 1,400 in the Damascus area Aug. 21 with a willingness to go it nearly alone -- without a United Nations mandate, congressional authorization or military assistance from the nation’s closest allies.

After the British Parliament voted down Prime Minister David Cameron’s proposed support of military intervention in Syria, only France has indicated it was ready to stand with the United States if it decides, as appeared likely Friday, to launch cruise missiles to punish the government of President Bashar Assad.

Obama arrived at this lonely place after months of internal debate and impromptu policymaking on a conflict that has vexed this White House. During Syria’s nearly 2 1/2 years of civil war, the president has been reluctant to wade deeply into the messy fight. Obama called for Assad’s removal, but his advisors tussled over how to aid rebels without strengthening radical Islamists in their ranks.

The president surprised some in his administration when he declared a year ago that he would not tolerate the use of chemical weapons.

“We have communicated in no uncertain terms with every player in the region that that’s a red line for us, and that there would be enormous consequences,” he said.

Obama’s red-line statement has become a point of debate, as some critics argue that it boxed the president into two bad choices: take no action and damage U.S. credibility by failing to back up a threat, or launch limited strikes that will do little to turn the tide in the war and will risk further destabilizing the volatile region.

A week ago, Obama raised concern about his ability to build a coalition, win a U.N. mandate and justify an attack under international law. On Friday, in a brief statement at the White House, he insisted that such concerns took a back seat to U.S. interests. His comments came shortly after Secretary of State John F. Kerry described the attack by Assad’s forces in horrific terms and said officials believed it had killed 1,429 people, including 426 children.

“This kind of attack is a challenge to the world,” Obama said. “We cannot accept a world where women and children and innocent civilians are gassed on a terrible scale. This kind of attack threatens our national security interests by violating well-established international norms against the use of chemical weapons.”

Obama said any response would be limited. For days, officials have emphasized that the goal would not be “regime change,” a phrase that brought up uncomfortable echoes of the Iraq war, which Obama opposed as senator. Instead, officials said, any action would be carefully calibrated to respond to the suspected chemical weapons attack.

Still, there were signs that Obama felt obligated to act.

“Frankly, you know, part of the challenge that we end up with here is that a lot of people think something should be done, but nobody wants to do it,” he said.

This is familiar territory for American presidents. Many presidents have been called on to intervene in hot spots. Obama, in his reluctance to intervene in Syria’s civil war, took an incremental approach that never relieved the pressure, said Jeremy Shapiro, a Syria analyst who until May was senior advisor to the assistant secretary of State for Europe and Eurasia.

“The last two years, we have been on a very slow walk down a slippery slope,” Shapiro said. “Every time there were calls for the president to do something, he would take one more step. All the steps tended to relieve pressure on the administration for two or three months. Then the pressure mounted because none of those things were aimed at solving the problem.”

Shapiro is among those arguing that Obama should not take military action. He is joined by a sizable portion of the public, according to an NBC poll of 700 adults that was conducted this week.

When asked whether the U.S. should take military action against the Syrian government in response to the use of chemical weapons, 42% of respondents said yes and 50% said no. But when asked whether they would support a limited airstrike on military targets or infrastructure used to carry out chemical weapons attacks, the numbers flipped: 50% would support such an action; 44% would oppose it.

The poll found nearly 4 in 5 respondents think Obama should be required to get approval from Congress before taking military action; just 16% said he does not need such authorization.

The president, like many of his predecessors, does not intend to seek congressional authorization, though many lawmakers in the GOP-controlled House have called on him to ask Congress to vote on whether to take military action. Nearly 200 House members, Republicans and Democrats, have called for a vote. An alliance of conservatives and liberals remains uneasy with military action and its potential costs.

Top White House officials convened another briefing Friday afternoon to try to build support in a wider swath of rank-and-file lawmakers. Afterward, Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) said, “There needs to be compelling evidence that there is an imminent threat to the security of the American people or our allies before any military action is taken. I do not believe that this situation meets that threshold.”

Meanwhile, defense hawks have stepped up calls for action. In a joint statement, two leading national security voices, Sens. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), pushed Obama to take a tougher stand -- quickly.

“We urge President Obama to delay no further in taking military action in Syria that could finally change the momentum of this awful and destructive conflict,” they said. And they also worried that the military action envisioned by the administration in response to this “historic atrocity” did not appear to “be equal to the gravity of the crime itself.”

Former President George W. Bush, whose conduct of the war in Iraq was castigated by Obama, told Fox News he’s “not a fan of Assad.”

“The president has to make a tough call,” Bush said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.