Still 1,000 miles from the border, migrant caravan pauses in Mexico to regroup

- Share via

Reporting from Huixtla, Mexico — This center of this town about 50 miles north of Mexico’s southern border has been transformed into a giant homeless camp.

Thousands of Hondurans began arriving here early Monday and by late Tuesday filled up the central plaza.

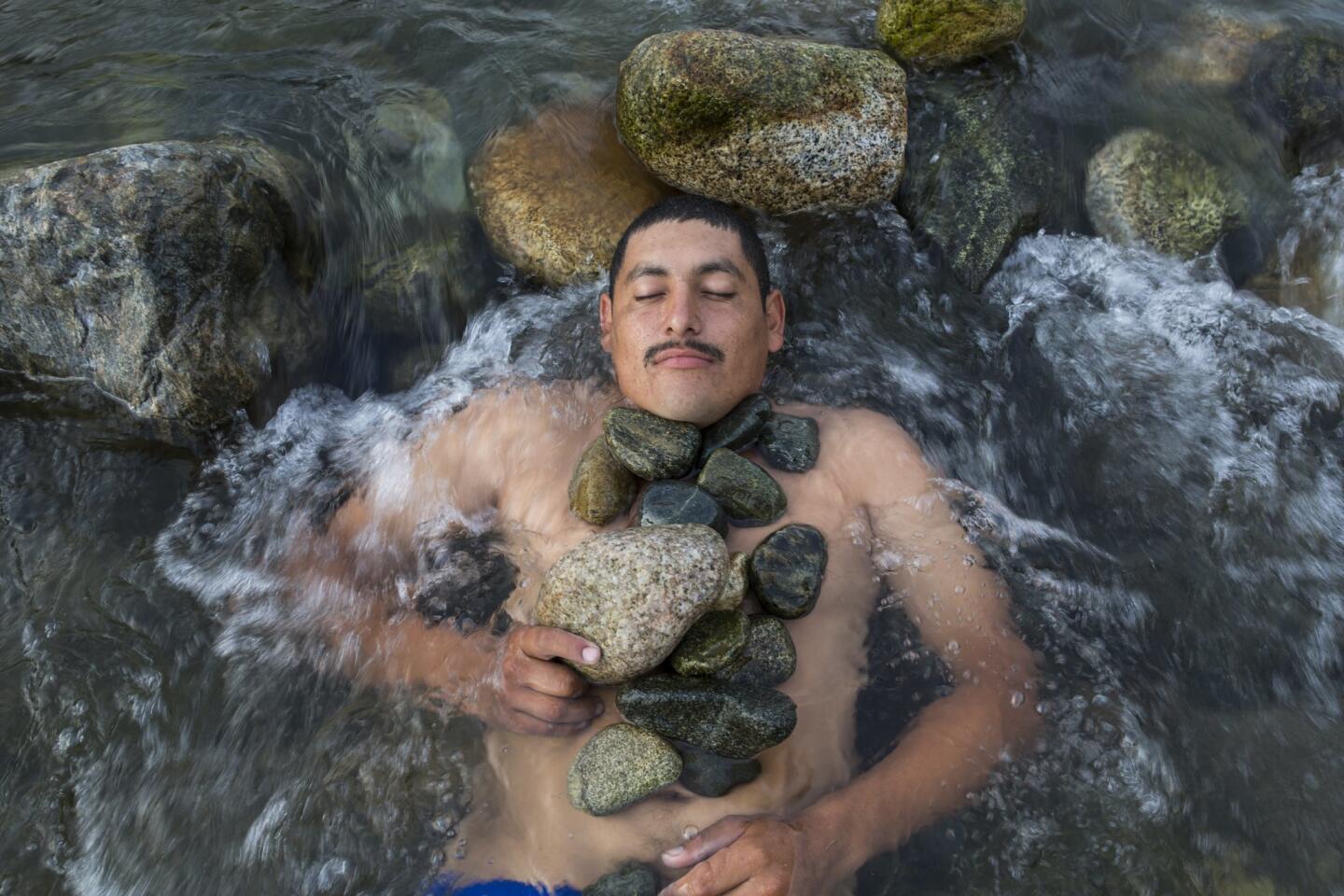

Exhausted, they decided to spend the day, seeking out whatever shade they could find from the subtropical swelter.

“We’re tired, we’re hungry, but we are determined to continue this journey,” said Evelyn Perdono, a 31-year-old mother of four who was seated on a low stone wall next to her sister and infant niece.

In the 11 days since the caravan left Honduras, the political controversy surrounding it has shown no sign of fading.

U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo told reporters Tuesday that without an accounting of who was in the caravan, it posed “an unacceptable security risk” to the United States. “You will not be successful in getting into the United States, illegally, no matter what,” he warned the migrants.

President Trump, who had tweeted that “Criminals and unknown Middle Easterners are mixed in” the caravan, acknowledged when pressed by reporters Tuesday that he had no evidence for that claim.

“There’s no proof of anything, but they very well could be,” Trump said during a bill signing in the Oval Office.

Read more: Is the U.S. really facing a border crisis? »

He said Border Patrol officials told him that “over the course of a number of years they’ve intercepted many people from the Middle East” including members of Islamic State, “wonderful people from the Middle East” and “bad ones.”

Vice President Mike Pence said it would be “inconceivable” that some Middle Easterners were not in the caravan, based on his own claim — which has since been widely debunked — that each day the United States prevents 10 terrorists or suspected terrorists from entering the country.

Back in Huixtla, hundreds of migrants used sticks and garbage bags to construct tents in the central plaza. They laid down blankets and strung ropes between trees to hang drenched clothing.

More drying garments were strewn on railings, benches and the pavement. The central gazebo was stacked with strollers, empty water bottles, backpacks and plastic sheets. Crushed cardboard boxes provided flooring.

For several blocks in each direction, caravan members rested after days of walking. A group of men played cards on the plaza pavement. People stared at their cellphones, having charged them in local shops.

Trash was everywhere. A man with a megaphone implored people to place garbage in huge white plastic bags that the town had placed in and around the plaza. All were overflowing onto the ground.

Residents of this town — the seat of a municipality that is home to more than 100,000 — seemed to take the sudden influx in stride.

“They are our brothers: It could be us in this situation,” said Samuel Orozco, an evangelical pastor who was helping to coordinate aid for the multitudes from a stage in the central plaza here. “Everyone is trying to help.”

Local volunteers handed out food, water, clothing and diapers and other goods. At one truck, people lined up for green apples. A man in a cart dispensed free glasses of the rice water drink known as horchata.

The town also provided some portable toilets and foldable tents.

Four Red Cross vans lined a side of the park, offering medical assistance and free two-minute calls back home on cellphones.

“Mostly people are dehydrated, suffering skin irritations, insect bites, exhaustion, headaches,” said Eric Fernandez Melgar, who was helping to coordinate Red Cross activities.

Mexican authorities have not attempted to stop the migrants from advancing northward from the Mexican border city of Ciudad Hidalgo, despite the presence of hundreds of Mexican federal police in the area. Thousands of migrants passed by a Mexican immigration checkpoint on Monday without being bothered.

The question for many is what will happen at the U.S. border.

“We hope Trump will let us in,” said Daisy Rodriguez, 45, as she fanned herself Tuesday on a park bench. “It’s hot, it can be boring, but we are continuing.”

Threats by Trump to call up the military along the border do not seem to faze the bedraggled travelers.

“We’ve come this far,” Rodriguez said.

In a reminder of the journey’s dangers, a young migrant was crushed by a vehicle Monday as the group traveled along the busy Pan American Highway. His bloodied body, covered by a sheet, lay on the highway for more than an hour before authorities removed it.

People stared at his remains, some sobbed, but everyone moved on.

There was talk among the migrants of holding a memorial for the young man, whose identity was not known.

The migrants planned to resume their journey by early Wednesday at the latest. No one seemed to know for sure.

On the road, the caravan is less an organized, fluid unit than a serpentine mass of humanity, stretching for miles. Some migrants hitch rides or jump onto moving tractor-trailers. Others just keep walking.

They march by banana and mango plantations and cattle pasture.

The U.S.-Mexico border is still more than 1,000 miles away. Just here in the southern state of Chiapas, the migrants must pass a half dozen Mexican immigration checkpoints.

Farther north, some migrants may jump on freight trains known here as La Bestia, or the Beast, a hazardous journey that has cost many Central American migrants their lives or limbs over the decades.

From the south, news has been emerging of new migrant caravans, some from as far away as El Salvador. Nobody here seems to know anything about that. They are similarly unaware of Trump’s hostile Twitter messages and political pronouncements, and somewhat bemused that their ragtag journey has taken on a kind of geopolitical weight.

“We have nothing but respect for President Trump,” declared Jose Rodriguez, 29, who carried a white flag lauding “Peace” and “God.”

The plan, apparently, is to trek from town to town, sleeping in plazas and on streets, resting for a day here and there, depending on the kindness of strangers and aid-givers.

The migrants say the hardships of the journey are worth the prospective payoffs — life in the United States, where, they all seem to believe, they can escape relentless poverty and crime and earn a measure of advancement, if not prosperity.

“The idea is to find some work and do what I can to help my children,” said Rodriguez, whose five children, ages 14 to 24, remained in Honduras for the time being. “Back home there is no future for anyone.”

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.