In Brazil, music for the flaunters and the wanters

Funk ostentacao, or ostentation funk, is the gospel of bling. Critics say rappers are sending the wrong message to Brazil’s many poor.

- Share via

Covered in tattoos and gold jewelry, MC Guime took the stage at a Sao Paulo club where patrons pay up to $4,500 for the VIP area, his lyrics fitting right in with the ostentatious surroundings.

"Top of the line! Nike Shox sneakers, Oakley shorts, Oakley shirt, look at us!" he belted out, celebrating some of Brazil's more popular brand names to a crowd of the playboy children of the country's elite.

The club usually puts on shows of safe, traditional Brazilian country music, a far cry from the thoroughly aggressive dance music known here as funk, which was born in Brazil's favelas, or slums. Guime flew through the set, delivering a frenetic ghetto beat and conspicuous-consumption lyrics about clothes, cars and champagne.

Two years ago this kind of lifestyle was little more than an aspiration for Guime. Since then, he's become the most famous face of funk ostentacao, or ostentation funk, an explosively popular new take on the genre that replaces themes of crime, poverty and social protest with a full-throated celebration of consumerist abandon.

It's a transformation familiar to historians of U.S. hip-hop, which gave birth to its bling phase in the 1990s and whose reigning king, Jay-Z, still excels at economic braggadocio.

But in Brazil, where tens of millions of people have risen out of poverty as the country surfed a boom powered by sales of commodities to China, the gospel of shopping is a relatively new phenomenon for ordinary people.

Popular music's exaltation of wanton spending and ostentation has made some uncomfortable, from members of the upper classes to left-leaning social movements defending the poor in the country, where the average salary is still just $780 a month.

Rapper MC Guime performs in Sao Paulo, Brazil. His message of conspicuous consumption is relatively new to the country, but it's one that has drawn fans by the millions. His video “Plaque de 100,” or “Stacks of Hundreds,” has been seen 45 million times on YouTube. (Isabelle Bottini / For The Times)

"I personally think ostentation funk is crude," says Gaia Passareli, a Brazilian music journalist and former host on MTV Brazil. "It goes too far venerating objects and distorted values."

Guime, born Guilherme Aparecido Dantas to a poor family in the broken-down outskirts of the city, understands the critics. But if the reality he affirms is perverse, the 21-year-old says, don't blame him.

"Before they complain about us, they have to complain about every TV channel, and all advertising, because we grew up seeing this, and how can I deny that we always wanted a nice car, if we grew up seeing that those respected in society have nice cars?" says Guime, his face dead serious behind sunglasses.

"Every day, on TV, the rich family is happy and the poor family is sad. How am I not going to want what they're allowed to have?"

In a country still marked by extreme inequality, Sao Paulo is home to Brazil's business elite, many of whom commute in helicopters to avoid the traffic below. Outside the gilded center, periferia neighborhoods stretch for miles and miles, marred by graffiti and poverty.

Guime grew up in Osasco, one of these neighborhoods, and began working when he was 11, at a street food stand.

"I always had various small jobs. That's why, thanks to God, I never went hungry at home," he says. "But we never had any more than was really minimally necessary."

It was only later that he realized music was a much better way to make a living.

Whether we like it or not, our society is capitalist. Should we deny this? ”— Rapper MC Guime

For much of its existence, Brazilian funk has been firmly underground and countercultural, often openly despised by the elite, its lyrics focused on poverty, social protest, love (often sex in explicit terms) and the reality of crime in Brazil's favelas.

The genre was born in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, a mash-up of Miami bass, a sub-genre of U.S. hip-hop; Brazilian lyricism; and increasingly frenetic beats.

One earlier famous funk anthem (reprised often by Guime), "Funk da Felicidade," proclaimed, "All I want is to be happy / here in the favela where I was born / be proud of myself / and know that the poor have their place."

But this message was largely set aside as the genre took on ostentacao themes.

"Whether we like it or not, our society is capitalist. Should we deny this? Should we not talk about the brands and companies that dominate here?" asks Guime, earnest and polite, speaking in his studio offices. "So we make music that is a kind of cry of freedom, to say, 'So what if we are from the favela? We have things too! We have a car!' That's the message we're sending."

Even in his most confident moments, and despite the walls of tattoos and gold, Guime seems careful and almost nervous when he speaks, eager to say the right thing or be gentle with fans.

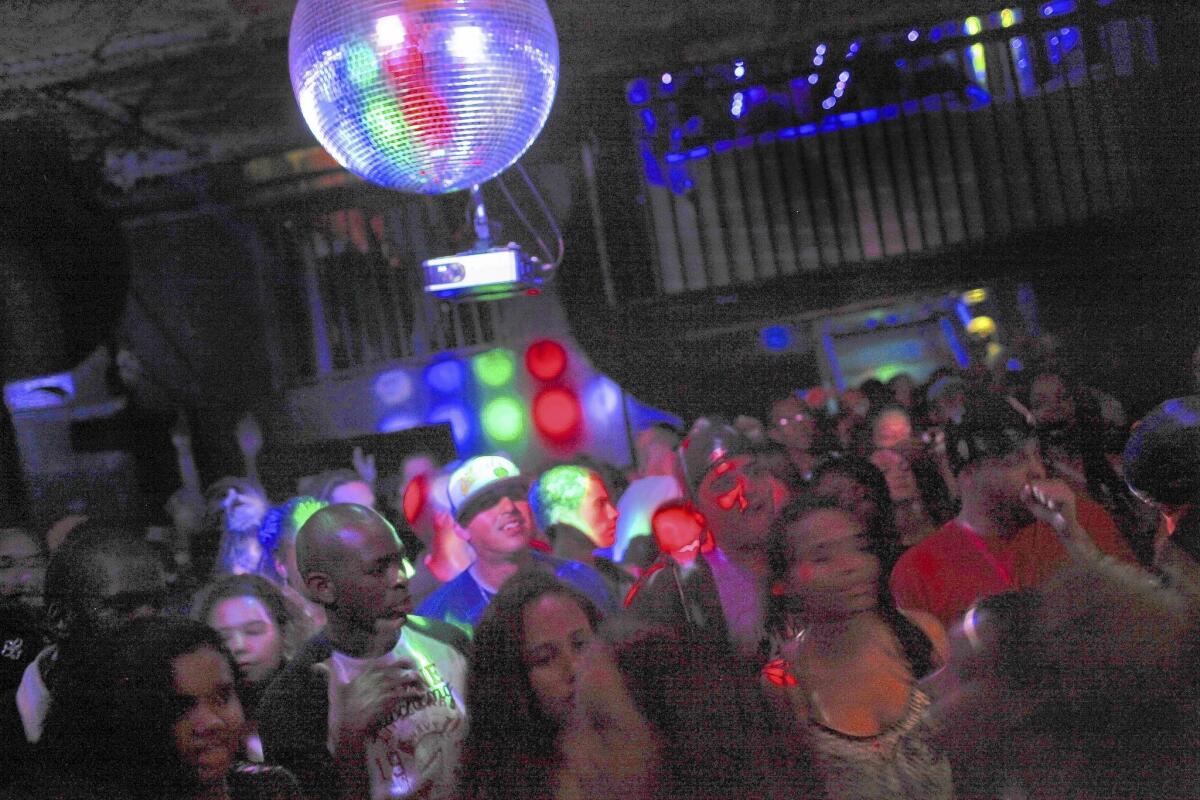

Dancers enjoy the music at the DJ Club in Sao Paulo's upscale Paulista neighborhood. (Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Those fans have flocked to him since he released his first music video when he was 19. Titled "Ta Patrao," or "It's Top of the Line," the video has been seen 21 million times. The 2012 clip "Plaque de 100," or "Stacks of Hundreds," has been seen 45 million times, almost 20 million more times than has the 2013 Jay-Z and Justin Timberlake collaboration, "Holy Grail."

Ostentacao has made two very different groups wrinkle their noses in distaste recently as it has gained force.

The first are traditional social movements that prefer left-wing politics and solidarity to displays of wealth.

"Ostentacao lyrics have absolutely nothing to do with the reality that kids in our poor neighborhood live in," says Rafael Ambrosio, who is a part of Davila, a graffiti, dance and low-rider collective in Sao Paulo's poor outskirts.

Ambrosio has Malcolm X tattooed on his arm and poses with Marx books on his Facebook page. "Where I live, kids are robbing to buy sneakers and go to expensive nightclubs.... These songs are creating illusions for these kids, who want to buy a $100,000 car but don't have enough to eat."

But Guime has been endorsed by Emicida, a popular left-leaning rapper, and together they made a clip for the song "Pais de Futebol" — "Football Country" — in which they argue that music is now, like sports always has been, a way for the poor to rise up without having to turn to crime.

Where I live, kids are robbing to buy sneakers and go to expensive nightclubs.”— Rapper Emicida

"When you're born in a place like this, people put you down, and it makes you stop believing in yourself," Emicida, sitting in a poor neighborhood, says in the video's intro. "But where do all the best soccer players come from? Here, just like the best musicians."

Another backlash has come from Brazil's traditional upper classes, some of whom have felt uncomfortable sharing space with the rising poor, who previously had kept to their neighborhoods.

In December, a group of kids organized a meet-up in a shopping mall. So many turned out, dancing and singing funk and wearing their best name-brand gear, that malls banned the so-called rolezinhos, or little strolls, and instituted door policies that many called discriminatory against the poor or dark-skinned.

The event's organizers said they had no political goals; malls were simply the only places in their communities where they could hang out.

MC Guime poses at the offices of his record label in Sao Paulo, Brazil. He understands the critics of his message, but says: "Every day, on TV, the rich family is happy and the poor family is sad. How am I not going to want what they’re allowed to have?" (Vincent Bevins / For The Times)

Laurindo Leal Filho, a sociologist at the University of Sao Paulo, says ostentacao songs come from the combination of increased buying power and cultural alienation.

"In Brazil, some parts of society began to be able to purchase more than just the necessary minimum, and are buying what was before considered superfluous, from shampoo to plane tickets," he says. "But this growth wasn't accompanied by policies that would increase the critical faculties of these classes in relation to consumption."

At Brook's Bar, where Guime was performing, brown-skinned Brazilians are still largely limited to cleaning toilets or working as security guards. And so for the singer and his team, his show was a bit of a triumph.

"Funk has been very discriminated against. It was always, "The guy is a funkeiro, he's a slob, he has no money," Guime says. "I wanted to prove the opposite."

Bevins is a special correspondent.

Follow Vincent Bevins(@Vinncent) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

More fans of the accordion are squeezing in lessons

I like to think that I've helped to bring sexy back to the accordion.”

Rose Hills cemetery cultivates Chinese clientele

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.