Arizona expects to be back at the center of election attacks. Officials are on offense

- Share via

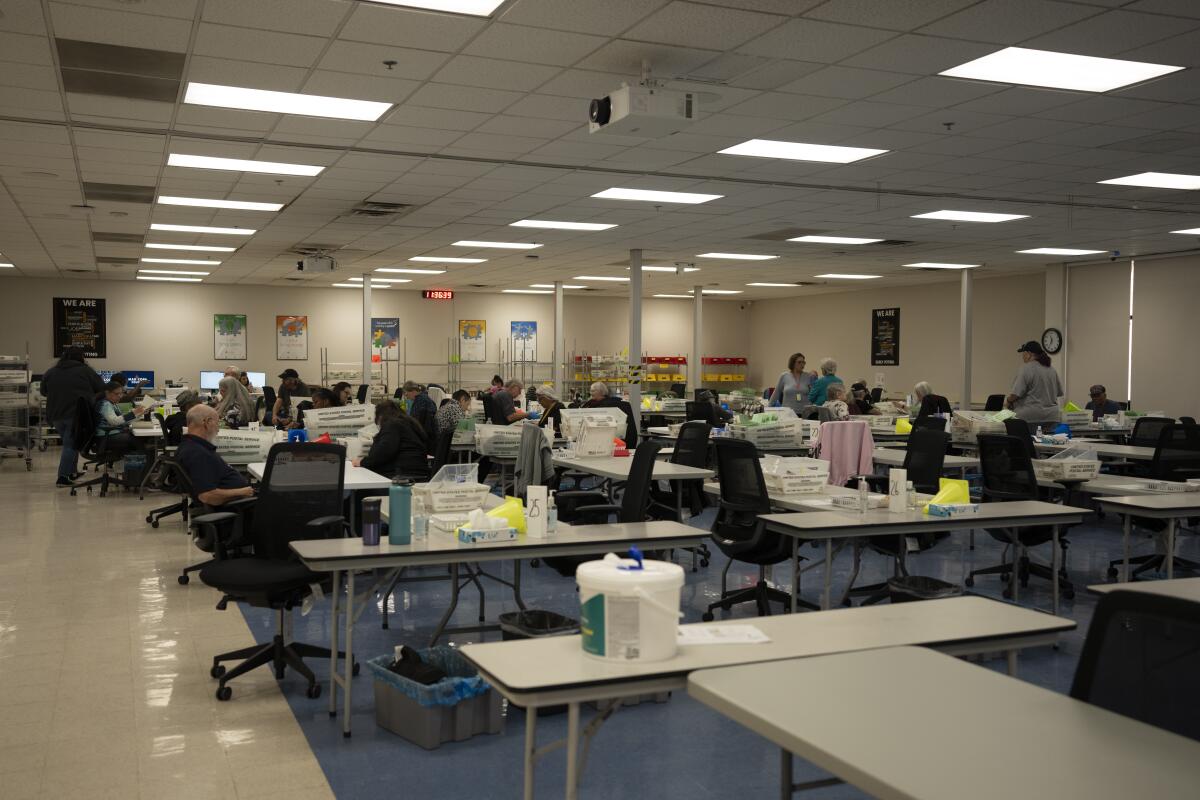

PHOENIX — The room sits behind a chain-link fence and iron gates. Guards block the entrance, which requires a security badge to access. The glass surrounding it is shatterproof.

What merits these layers of protection are machines that count votes in Arizona’s Maricopa County. The security measures are a necessary expense, said the county’s recorder, Stephen Richer, as Arizona and Maricopa have become hotbeds of misinformation that drives harassment toward election workers.

“What would be even more of a shame is if we couldn’t look the workers in the eye and say, ‘We’re doing everything possible to make sure that you’re safe,’” he said.

Richer’s job is to oversee registration and early voting in Arizona’s largest county, but much of his time has been diverted to preparing for disinformation and its consequences. The state’s razor-thin presidential outcome in 2020 made it a hot spot for conspiracy theories about voter fraud.

The false claims promoted by prominent Republican candidates have driven protesters to rally outside vote-counting centers and to patrol drop boxes. They have led to death threats against election workers and have prompted top officials to quit. Election meddlers have also attempted to hack Arizona’s electronic systems, Secretary of State Adrian Fontes said.

The challenges come as understaffed and underfunded election offices nationwide are dealing with persistent misinformation and harassment of election workers, artificial intelligence deepfakes, potential cyberattacks from foreign governments and criminal ransomware attacks.

With looming elections this fall, Richer, a Republican, and Fontes, a Democrat, are taking aggressive steps to rebuild trust with Arizona voters, knock down disinformation and immediately address threats.

They are hoping it’s enough to counter an onslaught they know is coming in November.

A new poll of California voters finds widespread concern over disinformation regarding politics and elections, but little agreement on whom to trust.

Fontes, a Marine veteran, has brought his military mind-set to the office since becoming secretary of state last year. He has deployed “tiger teams” to troubleshoot problems, hosted simulations on AI-generated disinformation and created a four-person information security team, one of whom is devoted solely to monitoring the internet for election-related disinformation.

Conservatives in other states have balked at election offices partnering with companies to track online postings, arguing that it enables government surveillance and censorship. Arizonans voting at this month’s presidential primary in the Phoenix suburb of Tempe also weren’t convinced.

“You’re monitoring it for threats? Sure. You need to ensure safety,” said 40-year-old Thomas Abia. But he called monitoring for falsehoods a “gray area.”

Fontes defends the need for a staffer to monitor internet disinformation.

“Yeah, we are surveilling a certain group,” he said. “We’re surveilling people that want to destroy our democracy. And that’s not political.”

Michael Moore, chief information security officer at Fontes’ office, used to do similar work for Maricopa County. After seeing threats to workers, he grew convinced that those who spread misinformation are responsible, he said.

“Sophisticated snake-oil salesmen are telling people what they want to hear in the election conspiracy vein — and that emboldens people to take action,” Moore said.

After the arrest of former Lodi City Councilman Shakir Khan, San Joaquin County election officials have struggled to regain voters’ trust.

Fontes and Richer agree that rebuilding public trust will require transparency.

Fontes is testing a statewide system for voters to receive text messages when their ballot is mailed, delivered, returned and counted. Richer recently hosted his first “Ask Me Anything” live video session on the social media platform X.

Still, many voters have doubts. Jane Carter, 62, a Republican, said her concerns grew when a 101-year-old she looks after received multiple ballots in the mail.

“I don’t have a lot of confidence in anybody that’s doing anything, really,” she said.

Signature verification and other security measures make the chances of fraud by mail ballot exceedingly low. But Richer said he has been culling voter lists to minimize the number of ballot packets sent to the wrong place, in hopes of boosting confidence in the process. His office also posts 24-hour live feeds of the tabulation center, even when activists have harassed the workers shown on camera.

“We continue to default on the side of transparency and then try to address the consequences when they’re negative,” he said.

Republican state Sen. Ken Bennett argues that even more transparency is needed. Last year, he sponsored a bipartisan bill that would have required detailed voter data and images of cast ballots to be put online.

The legislation, which Fontes supported, passed but was vetoed last May by Gov. Katie Hobbs, a Democrat. She said it threatened the anonymity of voters and unnecessarily burdened election workers.

Turning around public perception is proving difficult.

In the recent presidential primary, Richer noticed a conservative activist complaining on X about receiving two mailed ballots. Richer suspected she had changed addresses close to the election, resulting in a second ballot delivered to her new home. That would be no cause for concern: As soon as the new ballot went out, the county’s system would void the initial one, and it would never be counted.

Richer responded to the post to explain. But people used the post to claim that elections aren’t reliable.

Richer said he’s had to accept that some people won’t change their minds.

“I was a romantic who believed in sort of the marketplace of ideas — that, you know, gosh, the best ideas and the truth will bubble to the top, because man is a rational creature,” he said. “I’m not sure if I feel that way anymore.”

So when a voter during the presidential primary posted on X, “I don’t trust you,” Richer responded the best way he knew how.

“OK,” he wrote. “Let me know if there’s anything I can do to help you think otherwise.”

Swenson writes for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.