As monkeypox cases grow, so do fears of a return of gay blame and stigma

- Share via

BERLIN — As mysterious cases of a rare and ominously named virus began surfacing in Europe, Germany’s disease control center quickly told people to be on the lookout.

In a May 19 alert, the agency listed telltale symptoms of monkeypox: fever, aches, a rash. Then, in a further comment that set different alarm bells ringing, the bulletin pointedly warned men who have sex with men to “seek immediate medical attention” if they detect signs of the disease.

The singling out has sparked fears that gay and bisexual men, who appear to account for most of Europe’s monkeypox cases so far, are once again in danger of being stigmatized as carriers of an exotic and frightening disease, just as they were during the AIDS crisis.

Nearly 200 confirmed monkeypox cases have been reported in more than 20 countries outside Africa, where the virus is mostly found — including the first likely case in California, in Sacramento County, earlier this week. Although health officials are keeping a close eye on the outbreak, the caseload is minuscule compared with the 528 million coronavirus infections of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But as reports of the disease grab headlines, along with suggestions that the spread could be linked to a huge gay pride event in Spain’s Canary Islands, off the coast of Africa, some LGBTQ people and organizations are bracing for a backlash.

Here in Germany, where the Nazi regime once sent homosexuals to concentration camps, officials say there are already comments online vilifying the gay community, with some calling the virus “gaypox.” A piece of graffiti painted inside a Berlin train read: “HIV and monkeypox = gift to gays.”

Everything you need to know about monkeypox.

The country has recorded five monkeypox cases so far. Much larger numbers of infections have cropped up in other European countries, including Spain, Portugal and Belgium. Britain has more than 100 confirmed cases.

The bulletin put out by the Robert Koch Institute, Germany’s disease control center, has since been retracted, though the institute declined to state why. Some critics say the damage was already done.

“It’s important to pay more attention [to the disease], yes, but it’s a mistake to oversimplify, and, more than anything else, it’s totally wrong to assign any blame,” Tobias Oliveira Weismantel, managing director of the Munich AIDS Hilfe support group, said in an interview. “It’s misguided to attribute it to any particular group.”

A columnist for Der Tagesspiegel newspaper in Berlin was more blunt. The institute’s alert contained “only one sentence that directly addresses one group,” the columnist, Ingo Bach, noted. “For some the message quickly became clear: ‘Only gays get this.’ The threat of stigmatization is strong.”

On Tuesday, German Health Minister Karl Lauterbach tried to clear up misunderstandings about the outbreak, saying at a news conference in Berlin that it was not the start of a new pandemic and that monkeypox was not an ailment that afflicted only gay and bisexual men.

“It’s true that certain homosexual men — for example, sex workers — are now more affected,” said Lauterbach, who had been criticized for earlier singling out men who have “anonymous sex” as being especially at risk. “But the pathogen … can spread to all genders, to children, to adults and to adolescents.”

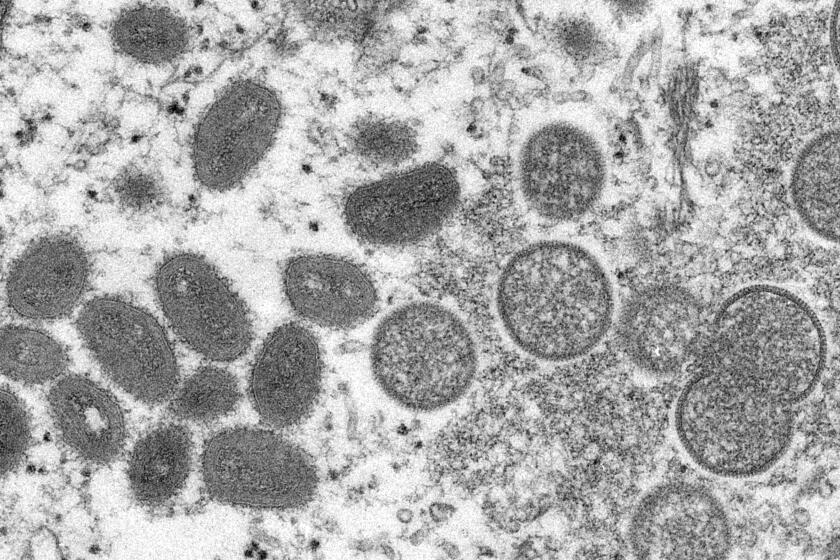

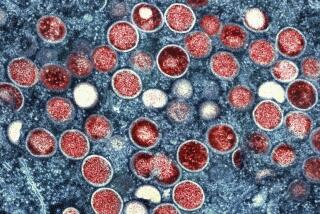

The virus, first discovered in 1958 in colonies of monkeys kept for research and in humans in 1970, is spread through close contact with an infected person, which includes sex but is not limited to it. Shared clothing or bedding can also result in transmission, as can, potentially, respiratory droplets.

Monkeypox is garnering increased attention because outbreaks and cases are showing up in areas where they don’t usually occur.

Most patients recover from the disease on their own, without hospitalization, within two to four weeks of the onset of symptoms. The World Health Organization says that, historically, up to 11% of people with monkeypox have died from it, with the rate higher among children. No deaths have been reported among the current cases.

A German government report to lawmakers this week said four of Germany’s confirmed cases were linked to exposure “at party events including on Gran Canaria and in Berlin, where sexual activity took place.” Gran Canaria, or Grand Canary, is one of the Canary Islands.

Lauterbach’s comments on the outbreak reflect the often-tricky position for health officials who want to warn populations that they think are particularly vulnerable to a disease without at the same time demonizing them.

“It’s really important to avoid panic and stigmatization,” said Markus Ulrich, a spokesman for Germany’s Lesbian and Gay Federation. “Yet that’s exactly what a lot of gay men are seeing right now in the language from the health minister and Robert Koch Institute. They need to take a look at how they’re communicating this. They need to enlighten without stigmatizing anyone.”

In the U.S., the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the HIV Medicine Assn. issued a joint statement Thursday condemning the “use of racist and homophobic language” with regard to the monkeypox outbreak.

“As we have repeatedly learned with HIV, substance use disorders, COVID-19 and other diseases, stigmatizing language that casts blame on specific communities undermines disease response and discourages those who need treatment from seeking it,” the statement said, adding: “Monkeypox is spread through close physical contact, and no one community is biologically more at risk than another. Viruses do not recognize global borders or social networks. Stigma has no place in medicine or public health.”

Janosch Dahmen, a leader and medical expert for the Greens party in the German parliament, said it was a mistake to focus on any particular group in the guidance on monkeypox.

“We’ve got to communicate more clearly that heterosexual contacts can also lead to monkeypox transmissions,” Dahmen said.

The care in messaging is important in a country that was long a bastion of ugly intolerance of LGBTQ people. Sex between men was criminalized from the outset of the founding of modern Germany in 1871, in a section of the legal code known as Paragraph 175.

The Nazis zealously persecuted gay men, shipping 5,000 to 15,000 to concentration camps, where they were forced to wear pink triangles as part of the camps’ prisoner classification system. Even after World War II, more than 50,000 men were prosecuted for gay sex under Paragraph 175, which was not repealed until 1994.

The convictions were nullified by parliament in 2017. That same year, Germany legalized same-sex marriage, one of the last major Western and Central European countries to do so (civil unions, but not marriage, were already allowed).

Cities like Berlin and Cologne are now home to vibrant gay scenes and huge pride celebrations. The capital has had a popular gay mayor, Klaus Wowereit, and former Chancellor Angela Merkel appointed Germany’s first foreign minister to come out as gay, Guido Westerwelle, in 2009. Under current Chancellor Olaf Scholz, the federal government now has a “commissioner for the acceptance of sexual and gender diversity.”

Chancellor Angela Merkel surprised Germans and her own conservative party just three months before the Sept. 24 election by abruptly signaling her support for same-sex marriage — a major shift for the normally cautious leader.

Nonetheless, some worry that the spread of monkeypox could be weaponized by homophobic segments of society.

“The question is whether homosexual and bisexual men will once again have a kind of ‘igitt’ [‘yuck’] label attached to them that will somehow devalue them just like back in the 1980s with AIDS,” wrote Bach, the newspaper columnist.

“There’s a fear that certain groups will see this as a welcome opportunity to say, ‘Look, homosexuals have brought upon us a new disease,’” added Weismantel of the Munich AIDS support group. “We’re already seeing a lot of that on social media. That kind of thing is especially dangerous in countries that are not so tolerant. …

“I really hope there won’t be a stigmatization, and believe our society has advanced and is better informed nowadays.”

Special correspondent Kirschbaum reported from Berlin and Times staff writer Chu from London.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.