Security protocols leave threat responses up to schools

- Share via

School systems nationwide rely on high-level expertise from the U.S. Secret Service and others as they work to stay vigilant for signs of potential student violence, training staff, surveilling social media and urging others to tip them off.

When it comes to how to respond to a possible threat, however, it’s the local educators who make the call.

In the Nov. 30 shooting at an Oxford Township, Mich., high school, authorities say the 15-year-old student charged with killing four peers was allowed to remain in school despite troubling behavior including a drawing of a handgun and a person with bullet wounds. The school’s handling of the student before the shooting is among the topics under investigation.

Security experts and school administrators say there is detailed guidance to help schools recognize concerning behavior and when to intervene. But exactly how to respond, including whether to remove students from school property or involve law enforcement, is for school officials to decide in each individual case.

Educators routinely assess how to deal with behavior that can include mentions of weapons in a social media post and students “joking” about bomb threats, all while weighing safety concerns against a student’s right to an education.

“There is no such thing as the perfect school safety and crisis response protocol,” said Stephen Brock, a lead author on the subjects for the National Assn. of School Psychologists’ curriculum.

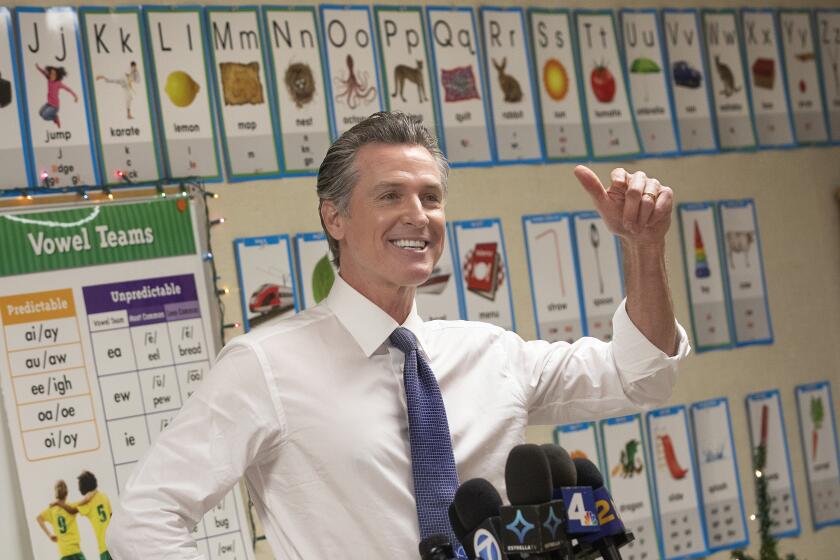

Newsom’s propensity for rattling off numbers and facts can feed into the public image of California’s self-assured and all-too-polished governor. But it’s also a byproduct of the lengths he goes to overcome insecurities from his learning issues.

Widely accepted best practices for threat assessment have been adapted from Secret Service guidance developed in the years since the 1999 Columbine school massacre. The agency’s National Threat Assessment Center recommends multidisciplinary teams of school administrators, security and mental health professionals be established to assess whether a student would be helped by counseling, should be reported to police, sent back to class or something in between.

To set blanket policy — for example, always sending students home for certain acts — would be to go backward to an era of zero-tolerance policies, when everyone was punished but few students got help, said Lina Alathari, chief of the Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center.

“You have to rely on your assessment to guide your response, which is why this multidisciplinary approach is so important. You want the mental health perspective, but you also want the [student resource officer] perspective because they will bring that operational, investigative mind set to ask the questions, whether something is an imminent risk or not,” she said.

Michael Lubelfeld, superintendent of North Shore School District 112 in Highland Park, Ill., described an “all hands on deck” approach whether a report comes in about a scuffle between students or a serious threat.

He recalled a scenario in one of the district’s middle schools last year, in which a child was overheard “indicating he wanted to do a violent act.” It was close to the end of the day, with little time to investigate. So he summoned police, who arrived in force.

“It was unsubstantiated but we didn’t have time to really do a thoughtful investigation,” Lubelfeld said, “so we basically called in the cavalry and then informed the community why we did it.”

“I would rather overreact,” he said, “and I can take the criticism for that.”

The Michigan attack came only hours after the defendant, Ethan Crumbley, returned to class after the school summoned him and his parents to discuss worrying behavior, including the drawing with the gun and the words: “The thoughts won’t stop. Help me.” Ethan told a counselor it was part of a video game he was designing.

After the shooting, authorities learned his father had bought a gun, which his son is accused of using, four days before. A prosecutor, in taking the unusual step of charging the parents with involuntary manslaughter, said James and Jennifer Crumbley knew their son had access to the gun but didn’t ask him about it after being shown the drawing, and resisted taking him home from school after the meeting. They have pleaded not guilty.

There are legal considerations for schools, especially if a student’s behavior is not found to pose an imminent risk, said Melissa Reeves, a psychologist and co-author of the NASP’s curriculum.

If parents don’t agree with the school and the situation doesn’t seem to merit intervention from a social services agency, “our hands are tied because we are legally obligated to educate,” she said. “We can’t deny access to education.”

Districts have faced lawsuits from parents claiming schools have overreacted and unfairly punished students for harmless remarks or actions or underreacted to tragic consequences.

“You’re damned if you do, you’re damned if you don’t,” said Dan Domenech, executive director of the School Superintendents Assn., a national group. In this third school year disrupted by the pandemic, he said, students are acting out more than ever, further straining the people tasked with figuring out if a student is just blowing off steam or about to erupt.

Meriden, Conn., Supt. Mark Benigni said the district has gotten pushback for searching students’ bags, sending them home or involving police.

“The last thing I want to do is keep a kid out of school, I know they can’t learn when they’re not here,” he said. “But at the end of the day, my obligation is to make sure I’m creating a safe environment, and I’m not going to apologize when I need to suspend a student.”

Near the start of the school year in September, an emailed threat from a high school student circulated among students at Fleming County Schools in Kentucky. The student was expelled after a review by the district’s threat assessment team. Supt. Brian Creasman said the student did not have access to weapons, but the team determined the student needed some kind of help.

“We’re going to take as long as we need to make sure we’re not putting that student who may have issues back into a classroom who could hurt him or herself or hurt others,” Creasman said.

“It’s not necessarily about punishing the kid for communicating the threat,” he said. “We want to help the kid address what is going on.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.