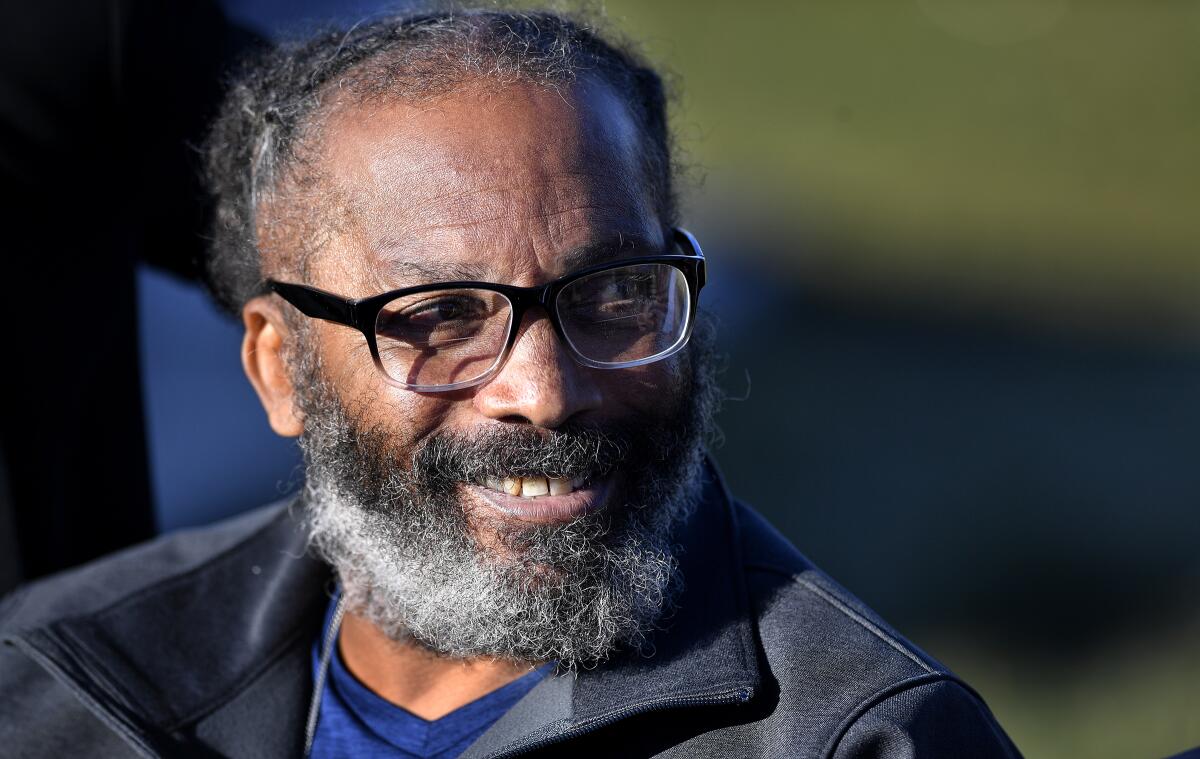

Missouri man exonerated in 3 killings, free after 40 years in prison

- Share via

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — A Kansas City man who was jailed for more than 40 years for three murders was released from prison Tuesday after a judge ruled that he was wrongfully convicted in 1979.

Kevin Strickland, 62, has always maintained that he was home watching television and had nothing to do with the killings, which happened when he was 18 years old. He learned of the decision when the news scrolled across the television screen as he was watching a soap opera. He said inmates began screaming.

“I’m not necessarily angry. It’s a lot. I think I’ve created emotions that you all don’t know about just yet,” he told reporters as he left the Western Missouri Correctional Center in Cameron. “Joy, sorrow, fear. I am trying to figure out how to put them together.”

He said he would like to get involved in efforts to “keep this from happening to someone else,” saying the criminal justice system “needs to be torn down and redone.”

Judge James Welsh, a retired Missouri Court of Appeals judge, ruled after a three-day evidentiary hearing requested by a Jackson County prosecutor who said evidence used to convict Strickland had since been recanted or disproved.

Welsh wrote in his judgment that “clear and convincing evidence” was presented that “undermines the Court’s confidence in the judgment of conviction.” He noted that no physical evidence linked Strickland to the crime scene and that a key witness recanted before her death.

“Under these unique circumstances, the Court’s confidence in Strickland’s convictions is so undermined that it cannot stand, and the judgment of conviction must be set aside,” Welsh wrote in ordering Strickland’s immediate release.

Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker, who pushed for his freedom, moved quickly to dismiss the criminal charges against him so he could be released.

“To say we’re extremely pleased and grateful is an understatement,” she said in a statement. “This brings justice — finally — to a man who has tragically suffered so so greatly as a result of this wrongful conviction.”

But Missouri Atty. Gen. Eric Schmitt, a Republican running for the U.S. Senate, said Strickland was guilty and had fought to keep him incarcerated.

“In this case, we defended the rule of law and the decision that a jury of Mr. Strickland’s peers made after hearing all of the facts in the case,” Schmitt spokesman Chris Nuelle said in a brief statement. “The court has spoken, no further action will be taken in this matter.”

Gov. Mike Parson, who declined Strickland’s clemency requests, tweeted simply that: “The Court has made its decision, we respect the decision, and the Department of Corrections will proceed with Mr. Strickland’s release immediately.”

Strickland was convicted in the deaths of Larry Ingram, 21; John Walker, 20; and Sherrie Black, 22, at a home in Kansas City.

The evidentiary hearing focused largely on testimony from Cynthia Douglas, the only person to survive the April 25, 1978, shootings. She initially identified Strickland as one of four men who shot the victims and testified to that during his two trials.

Welsh wrote that she had doubts soon after the conviction but initially was “hesitant to act because she feared she could face perjury charges if she were to publicly recant statements previously made under oath.”

She later said she was pressured by police to choose Strickland and tried for years to alert political and legal experts to help her prove she had identified the wrong man, according to testimony during the hearing from her family, friends and a co-worker. Douglas died in 2015.

During the hearing, attorneys for the Missouri attorney general’s office argued that Strickland’s advocates had not provided a paper trail that proved Douglas tried to recant her identification of Strickland, saying the theory was based on “hearsay, upon hearsay, upon hearsay.”

The judge also noted that two other men convicted in the killings later insisted Strickland wasn’t involved. They named two other suspects who were never charged.

During his testimony, Strickland denied suggestions that he offered Douglas $300 to “keep her mouth shut,” and said he had never visited the house where the murders occurred before they happened.

Strickland is Black, and his first trial ended in a hung jury when the only Black juror, a woman, held out for acquittal. After his second trial in 1979, he was convicted by an all-white jury of one count of capital murder and two counts of second-degree murder.

In May, Peters Baker announced that a review of the case led her to believe that Strickland was innocent.

In June, the Missouri Supreme Court declined to hear Strickland’s petition.

In August, Peters Baker used a new state law to seek the evidentiary hearing in Jackson County, where Strickland was convicted. The law allows local prosecutors to challenge convictions if they believe the defendant did not commit the crime. It was the first time — and so far the only time — that a prosecutor has used the law to fight a previous conviction.

“Even when the prosecutor is on your side, it took months and months for Mr. Strickland to come home and he still had to come home to a system that will not provide him any compensation for the 43 years he lost,” said Tricia Rojo Bushnell, executive director of the Midwest Innocence Project, who stood by Strickland’s side as he was released.

The state allows wrongful imprisonment payments only to people exonerated through DNA evidence, so Strickland doesn’t qualify.

“That is not justice,” she said. “I think we are hopeful that folks are paying so much attention and really asking the question of, ‘What should our system of justice look like?’”

Hollingsworth reported from Mission, Kan., and Stafford from Liberty, Missouri.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.