Asian American Christians confront racism and evangelical ‘purity culture’ after Atlanta spa shootings

- Share via

Before Robert Aaron Long burst into three Atlanta massage spas and allegedly killed eight people — six of them women of Asian descent — he was a teenager struggling to conform with Evangelical teachings on “purity culture” and abstinence from sex.

The Rev. Chul Yoo knew Long back then. A former minister in Long’s church, Yoo understood the pressure and obligation the young in the congregation faced in resisting premarital sex. The Bible wanted them sanctified and saved from the immorality of an increasingly permissive world.

But when news broke last month that Long claimed he killed the women to erase temptation, Yoo, a Southern Baptist preacher and an Asian American, also recognized why a nationwide outcry erupted against an accelerating racism toward people who looked liked him. For Yoo, rigid religion and racial hatred had become entwined in one of the nation’s worst mass shootings since the COVID-19 pandemic emerged last year.

The deadly Atlanta-area spa shootings have raised questions about the history of hate crime laws and why so few hate crimes are prosecuted.

Investigators have offered little on the motive in the Georgia deaths. There is no hate crime charge. Statements from law enforcement and those who knew Long point to someone ridden with guilt and anger over his visits to Asian-run spas that he believed went against the word of God.

“He would come back and say, ‘I’ve done it again,’” said Tyler Bayless, 35, who lived with Long at a halfway house in Roswell, Ga., from August 2019 until early 2020, when Long left for HopeQuest, a Christian addiction center. Bayless described Long as “from a very traditional religious background” where “the thoughts that he had about himself were certainly reinforced by the members of his own congregation.”

What’s described broadly as “purity culture” is well-known in evangelical communities. The teaching persists today in some factions of the church after reaching its height in the 1990s and early 2000s. It looks toward a Thessalonians passage in the Bible as a basis for how unmarried teens and young adults should live: “For this the will of God, your sanctification: that you abstain from sexual immorality; that each one of you know how to control his own body in holiness and honor....”

Purity pledges and a canon of books and conferences on teenage sexual purity were once so common that they had even made their way into pop culture, with singers Miley Cyrus, Selena Gomez and the Jonas Brothers famously donning purity rings.

But for Christians like Yoo, now the pastor of Christ Community Church in Ashton, Md., the meanings behind the spa killings are deeper and more troubling than Long’s comments to police about his sins. They are personal for Yoo in ways unlike other mass shootings, crossing lines of race, nationalism, immigrant culture and gender dynamics in conservative Christianity.

“We have a problem in the nation. I think of my own mother when elderly Asian woman are attacked. I look at the former president saying ‘kung flu’ and see the connections to hatred,” said Yoo, 49, who leads a congregation largely made up of second-generation Korean Americans. “And in parts of church communities, we are silent on this racism and misteach what the Bible says. It says sex is only for a married man and woman. It doesn’t say that girls are at fault for being a temptation.”

The Atlanta killings came after a year of rising hate crimes and harassment against Asian Americans, many tied to verbal taunts blaming them for the COVID-19 pandemic that echoed former President Trump’s rants against China. The deaths also happened as Christians of color were in a civil war of faith with white, conservative evangelicals who appeared united with them in core beliefs but divided over politics and how common and pernicious racial prejudice could be.

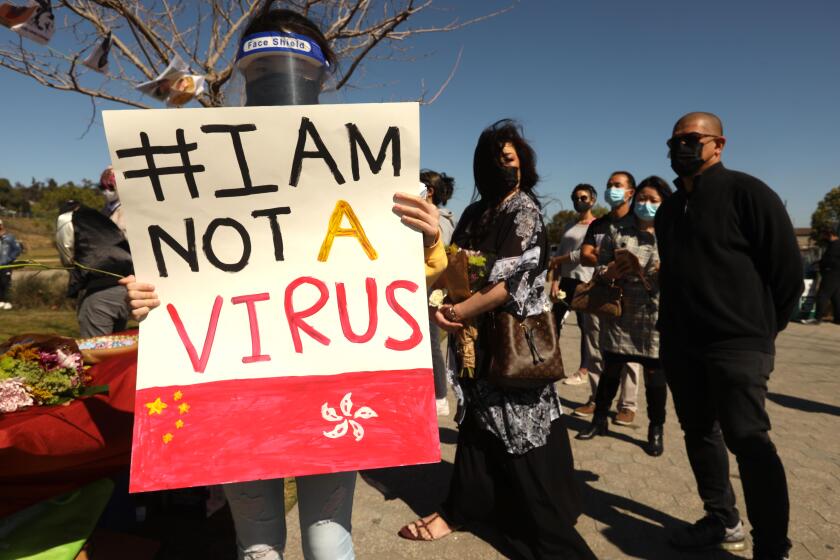

In the aftermath of the Atlanta shootings, Asian American Christians, a millions-strong community where conservative Protestant traditions reign and the sting of racism has long been felt within and outside church walls, have found a new megaphone. They’re leading marches, defending the faith and becoming outspoken critics of trends in “purity culture,” segregation and strict gender roles still popular in some corners of the church.

Here’s what we know about the victims in the attacks on three Atlanta-area spas that left eight people dead, including six women of Asian descent.

“This is a unique moment for the Asian American church,” said Yoo, “because we are grieving all around.”

Long’s church, Crabapple First Baptist in Milton, Ga., expelled him after the shootings, saying in a statement that he was no longer a “regenerate believer in Jesus Christ.”

Church leaders declined an interview request. The church posted on its website that Long “alone is responsible for his evil actions and desires. The women that he solicited for sexual acts are not responsible for his perverse sexual desires nor do they bear any blame in these murders.”

(Yoo, who worked at the church from 2012-15, described it as “a loving, caring community” that was “like all other churches, not perfect.”)

For some Asian American Christians, the church’s statement fell short and underscored the chasms that separate them within Christianity in the U.S.

“They denied their responsibility,” said the Rev. Byeong Cheol Han, 57, the lead pastor at Korean Central Presbyterian Church, about 10 miles northeast of two of the Atlanta spas. “He’s [Long‘s] a very active church member. In many ways, I assume, the church’s teaching must have given some kind of idea of discrimination or purity culture.”

Hate crimes against Asians and Asian Americans jumped dramatically in major U.S. cities in 2020.

To the Rev. Lauren Lisa Ng, a Chinese American pastor who is the director of leadership programs for the American Baptist Churches USA, the focus on the suspected killer’s faith and church has been discomfiting yet necessary.

“I have problems with how we seek to blame a specific institution. Maybe the church has some culpability,” said Ng, who lives in Novato, Calif., and recently organized a protest against anti-Asian racism in nearby San Rafael. “But the church as a whole in the world doesn’t. This isn’t Christianity’s fault alone.”

Across the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination in the nation, the shootings have reverberated as a reminder that the church’s heterosexual family-oriented culture can also be misinterpreted to support sin by denigrating and blaming women for the sexual desires of men.

Russell Moore, a prominent Southern Baptist writer and speaker who leads the church’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, suggested that the Atlanta killings were an example of “how evil works.”

“We’ve seen abusers and those who empower them label the abused as ‘Jezebels’ or ‘temptresses’ or ‘Potiphar’s wife.’ I have heard chilling testimony from innocent survivors who heard abusers blame them ‘for what you are making me do,’” Moore said.

“For most people, that won’t result in anything approaching those extremes,” he said, “but the tendency is there for all of us to take what is internal twistedness or shame and — instead of taking it to the light of Christ — to project it onto another.... This is not the gospel.”

The emotional toll of the Atlanta-area attacks and COVID-19 grief is amplifying longtime inequities in mental health care available for Asian communities.

“Purity culture” led some followers to abstinence, said the Rev. Mihee Kim-Kort, an Annapolis, Md.,-based pastor of a progressive Presbyterian church who grew up in a more conservative Korean immigrant-run Presbyterian congregation in Boulder, Colo., not far from Colorado Springs, a longtime bastion of prominent evangelical leaders and nonprofits. “But more often what it really became was a theology of shame focused on women.”

Kim-Kort, 42, remembers her parents giving her a purity ring before she went to college; it was a yellow-gold shank with a pearl. The memory came back to her when she heard police say Long had blamed his own temptation for his acts. She immediately thought of connections to her faith.

To Kim-Kort, who said her church “has made a point to be active in Black Lives Matter and the #StopAAPIHate movements,” it’s a “cop-out to say this crime is simply about sex addiction or religious culture. It’s all connected. It was about sexuality, race, gender all at once — all focused on Asian women.”

In Chicago, the Asian American Christian Collaborative has rallied around the victims in Georgia, with members attending demonstrations in Atlanta to talk about the role the more than 18 million Asian Americans, more than 40% of whom are Christian — most of them Protestant — play in the evangelical world.

The group launched a year ago with an open letter calling on evangelicals to “stop minimizing anti-Asian racism” and recognize that “Asian American churches are a vibrant part of the American fabric.”

In the secular world, it was racist responses to the COVID-19 pandemic that spurred the collaborative’s creation. In churches, it was a sense of being unseen as Asian Americans who were often stereotyped as either nonbelievers or followers of Buddhist, Hindu and other faiths that originated in Asia.

The Rev. Michelle Ami Reyes, the co-pastor of Hope Community Church in Austin, Texas, and vice president of the collaborative, said the hate incidents in the months leading to what she now simply calls “Atlanta” have “unfortunately proved us right.”

“There are so many questions around these deaths,” she said. “There’s no doubt racism is happening in the U.S.”

“There’s also no doubt that the fetishization of Asian women is normalized, even in church. And there is no doubt that there is a history in evangelical Christianity of promoting ideas of female purity,” said Reyes, 34, who is Indian American. She grew up in a suburban Minnesota congregation where reading the book “I Kissed Dating Goodbye” was “sort of required as a guidebook to female purity.” (Joshua Harris, the former megachurch pastor who released the title in 1997, eventually apologized for the book and said he is no longer Christian.)

Americans are still seeking answers — and justice — in the deaths of those who died in Atlanta. The #StopAAPIHate marches continue, as do conversations on where church fits into it all.

The Rev. Kevin Park said the last weeks have been a reminder of his view that churches have long failed at teaching about sex or race. He’s also seen the need for white communities to learn more about Asian American church traditions.

“Churches, in general, do not have Biblical healthy ways of talking about sex and sexuality,” said Park, an associate pastor at Korean Central Presbyterian Church in Atlanta. “It’s a historic reality. Given the conservative nature of the Korean church, this reflects on us too.

“The classic ways we teach about sex is to be very binary: ‘This is evil.’ ‘This is not good,’” he said. “Once you shut down a behavior as a sin or evil, that means we can’t go there, we can’t talk about it.”

That, Park said, is where the problems begin.

Kaleem reported from Los Angeles and Jarvie from Atlanta.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.