Nein for five: Facing a housing crunch, Berlin bans rent increases for 60 months

- Share via

BERLIN — At a showing for a small apartment, Lena Vasiljeva was surprised to find a crowd of 60 potential renters — and intuitively figured she and her husband had little chance, especially because they’re foreigners.

“It’s become really, really hard to find an apartment in Berlin,” said Vasiljeva, a 36-year-old software developer from Russia who applied for 120 apartments in a 35-day full-time search, before finally succeeding.

“Even though we both have well-paying jobs,” said Vasiljeva, whose husband is from Latvia, “trying to find an apartment in Berlin is no fun at all.”

House hunting in Berlin could become even more difficult in the years ahead after the city’s controversial five-year rent freeze, announced last June, takes effect on Sunday. The measure freezing prices at June 2019 levels, which is being challenged in court, can also force landlords of some 1.5 million private and public housing units in Berlin to lower rents if they’re deemed excessive.

The Mietendeckel (or rent cap), as it is known, was designed by the city government to apply a brake on what was deemed, by Berlin standards, a steep hike in rents over the last decade. Berlin has turned into a boom town, and once dirt-cheap rental prices started to catch up to levels in other major German cities — though they remain far lower than in London, Paris, New York and Los Angeles. The average monthly rent for a two-bedroom (900-square-foot) apartment in Berlin is now about $600, up 60% since 2000, according to city government figures.

Some renters, such as Vasiljeva and her 41-year-old husband, Anton, also a software developer, pay upward of twice that amount for modest one-bedroom apartments near the center of the city. The new law will allow renters paying more than the cap of $10.80 per square meter, which works out to about $900 per month for an average, 900-square-foot apartment, to petition the city to try to force landlords to lower the rent.

The cap is being closely watched by other cities, both across Germany and around the world, that are searching for antidotes to rapidly rising rents. So far, it is hugely popular among the legions of renters in Berlin, especially in the formerly communist eastern half of the city, where Cold War-era generations paid a small fraction of their income for housing and nostalgia for those glorious days behind the Iron Curtain runs high.

Some city leaders, mostly from the eastern districts of Berlin, have been clamoring for measures as extreme as expropriating property from private developers who pushed rents higher on 200,000 apartments that the city privatized more than a decade ago.

Critics warn that the cap on rents — and talk of eminent domain — in a city that at times is still struggling to fully come to terms with its communist past has been scaring away private investors. It will also, they worry, slow housing construction, and thus probably exacerbate the housing shortage in a city where more than 80% of the population are renters.

“Some investors will certainly be frightened away from Berlin by the rent cap, but it’s no big loss to see them go because they were evidently only interested in making lots of money,” said Wibke Werner, deputy director of the Berlin Mieterverein renters association, in an interview. Landlords, sometimes seen as villains in Berlin, in theory face fines of up to $550,000 if they refuse to lower rents to the cap’s upper limit.

“Sure, it’s intervening in the free market,” she added. “But regulation is needed when markets get out of control. The rent cap will give renters in Berlin breathing space for a few years so that the supply can hopefully catch up with demand.”

Rent hikes have been spurred by a growing population since the federal government’s move to Berlin in 1999, and an influx of foreigners, including refugees from Syria and elsewhere. Since 2012, the city’s population has increased to to 3.7 million, up by 250,000.

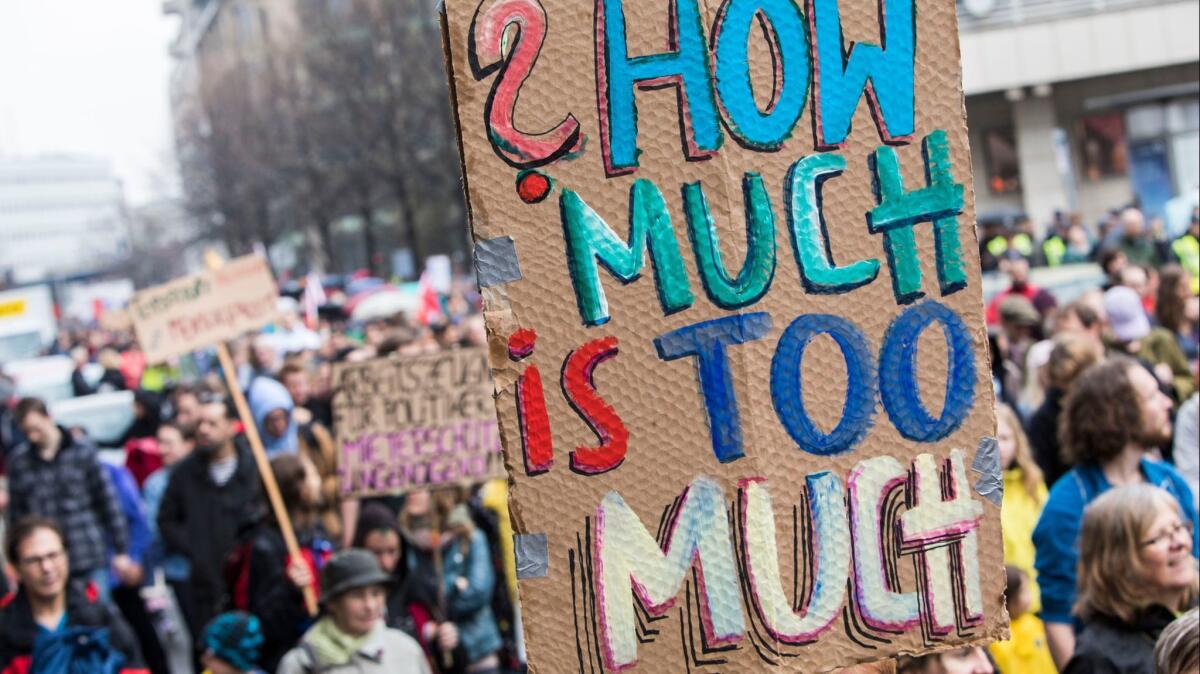

Tens of thousands of demonstrators have marched through Berlin over the last two years to demand a halt to rising rents, which developers and rent protection groups also blame on increasingly complex building regulations that have hindered housing construction.

“There just aren’t enough apartments in Berlin to meet the demand and there are some speculators pushing prices to indecent levels,” said Michael Zahn, the head of Deutsche Wohnen, a company that rents 110,000 apartments in Berlin, in a recent interview with Der Tagesspiegel newspaper. “The problem is high demand. The rent cap is only going to cause chaos and disharmony.”

Berlin has a long tradition of providing considerable state support for low-cost housing. Mayors from the major political parties on the left and right have backed heavy investment in housing for the working class and subsidies so that teachers, police officers, firefighters and nurses can afford to live in any section of Berlin — even in the heart of the city.

As a result, many developers long avoided Berlin. Unemployment was long higher here than in the rest of Germany, rents were cheap and property prices even declined in many parts of the city during the 1990s and early 2000s.

Berlin, which was dubbed “poor but sexy” in 2003 by its former Mayor Klaus Wowereit, sold off more than 220,000 of its 360,000 rent-subsidized social housing units for a pittance when prices were depressed more than a decade ago — a move it now regrets.

“No one thought back then that Berlin would be the boom town it’s become,” said Zahn, whose company rents its apartments for an average of $600 per month for a 900-square-foot unit — well within the rent cap. “The city was in a precarious financial situation. But that’s not the problem now. The problem is that there aren’t enough apartments.”

The German Constitution guarantees the right to Wohnraum (a place to live), and renter advocates reject the notion that apartments are like any other commodity. But leaders of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative party, who are challenging the rent cap in court, argue that the constitution also stipulates that the federal government, and not state or city governments, are responsible for housing rents.

“It’s our job to stop the speculators,” said Werner, who is confident the measure will survive the court challenge.

Kirschbaum is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.