Column: E = mc² = World Series champion? Why Rangers have the smart kids

- Share via

The Texas Rangers will ride in a championship parade Friday, holding the World Series trophy aloft in celebration of a group of players that had it all: big bats, big arms, and big brains.

For all the accomplishments and records of the first title team in the 63-year history of the franchise, this one might stand alone: The Rangers could be the first major league champion with two high school valedictorians on their roster.

“Pretty cool, right?” said Texas general manager Chris Young.

The World Series features two wild-card teams. Commissioner Rob Manfred says the unpredictability of the postseason is a bonus.

There is no way to know for sure. It is not something you could look up at Baseball Reference.

We asked the intrepid researchers at the Hall of Fame, and they could find no record of two valedictorians on any major league roster, let alone a championship roster. They did find a handful of players who had been listed as valedictorians, including Hall of Famer Johnny Bench and just-retired pitcher Trevor May.

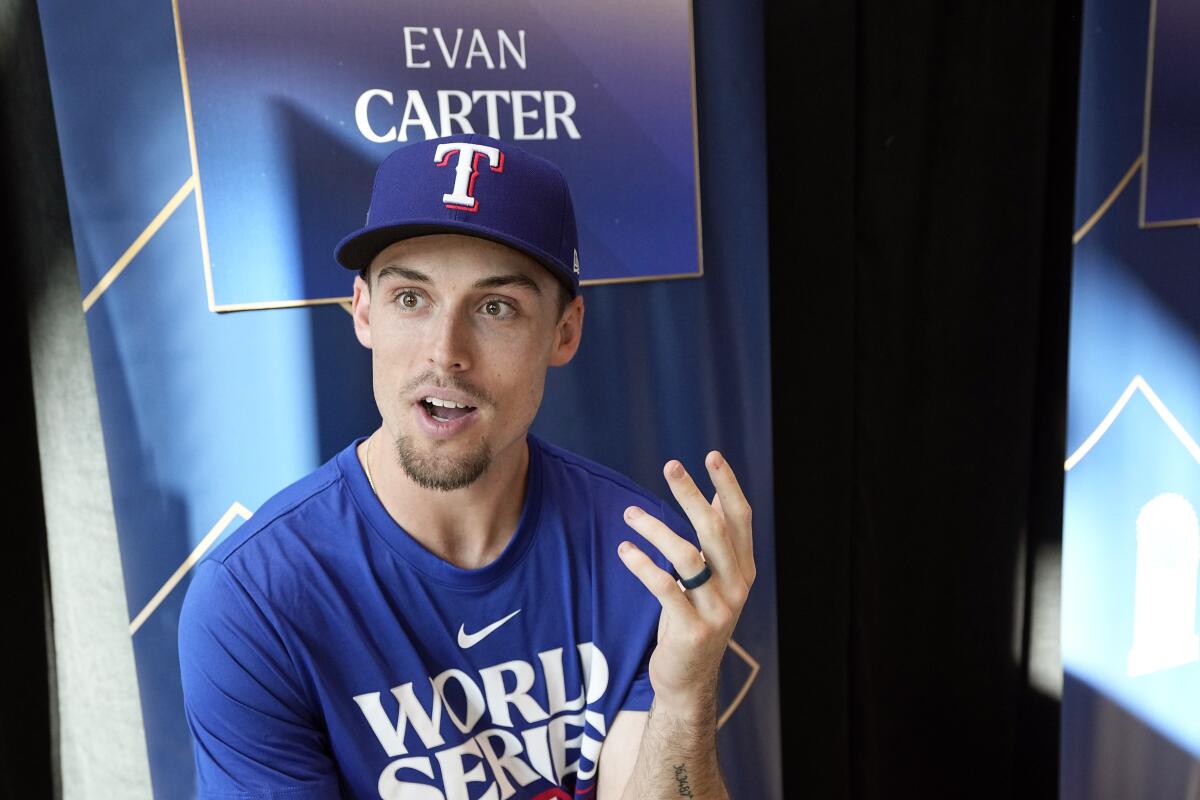

The Rangers’ valedictorians: rookie outfielder Evan Carter, who batted cleanup in the World Series at age 21, and rookie reliever Cody Bradford, who posted a 1.17 earned-run average in five postseason appearances.

“If you have a good work ethic and you know how to work hard, that’s not just going to help you in academics,” Bradford said. “That’s going to help you in life, being a good husband. That’s going to help you in any walk of life.”

Bradford, 25, grew up in Aledo, Texas, about 35 miles west of Globe Life Park. On his LinkedIn page, he describes himself as “Supply Chain Graduate and Professional Athlete.”

That is no joke. He graduated from Baylor with a 4.0 grade point average and a business degree, with an emphasis on “logistics, materials, and supply chain management.” His SAT score: 1990.

Carter grew up in Elizabethton, Tenn., with his course firmly charted: He would play baseball at Duke, then go to dental school to become an endodontist.

Endodontists make up 3% of all dentists and specialize in “treatments of the dental pulp” that can save diseased teeth, according to the American Assn. of Endodontists.

In 2020, the year he graduated from high school, Carter was not listed among Baseball America’s top 500 prospects. The Rangers nonetheless selected him with the 50th pick in the draft and signed him for $1.25 million.

“School is always going to be there, but the opportunity to play pro ball is not, so this was the route I wanted to take,” he said.

The Rangers promoted him to the major leagues in September, 10 days after his 21st birthday, and now Carter is an anchor on a World Series champion. Does he still plan to go to college after his career ends?

“No,” he said, laughing. “I’ll be an electrician or something at this point, if I go back and do anything like that.”

The valedictorian traditionally delivers a speech to the graduating class. Carter said he was relieved that he did not have to do that.

“We didn’t have our own graduation,” Carter said. “It was the COVID year. But I would say talking in front of people is a lot worse than playing.”

Bradford said pitching in the playoffs made him more nervous than talking to his graduating class. He still remembers what he told his classmates.

“One of my main points was that it doesn’t really matter how gifted or smart you may be,” he said, “what matters more is what kind of work ethic you have.

“You don’t have to be the most talented. You don’t have to be the fastest, the strongest, the smartest person. But, if you work hard, you can figure it out from there.”

If you cannot hit a fastball, or you cannot throw a ball fast, all the smarts in the world are not going to get you to the major leagues. But, all other things being equal, being a valedictorian counts for more than just a line in the graduation program.

MLB players are excited about the prospect of playing in the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics. So why won’t the league commit to making it happen?

“There are some people that are so smart they get by just by being brilliant, but most people have to work hard to succeed,” Young said. “I think it’s a character trait that shows up in the other areas of your life. Certainly, the way that these guys work and prepare, it’s no coincidence.”

Young can appreciate this more than most baseball executives. He played baseball and basketball at Princeton, then pitched for 13 years in the major leagues.

If baseball players are supposed to be role models, Bradford and Carter are not bad choices, right?

“Not at all,” Young said. “I don’t want to say we’re a team full of choir boys by any means. But you try to choose people that are going to maximize their potential, and those guys do that.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.