Commentary: Taxpayer money for a stadium? It’s Rob Manfred vs. the economists

- Share via

SEATTLE — In 2001, seven years after two NFL teams abandoned Southern California, I asked a Los Angeles mayoral candidate whether voters wanted him to lobby the NFL to return.

Ninety percent of voters didn’t care, he said. And, of the 10% that did care, 90% of them emphasized the city should not spend a dime of its own money on a stadium.

The NFL eventually got the message. The Rams returned in 2016, and the owner paid for the stadium. The Kings’ owners financed Staples Center, now Crypto.com Arena. The Clippers’ owner is paying for a new arena. The Dodgers’ owners have spent hundreds of millions to renovate their stadium, built with private funding more than 60 years ago.

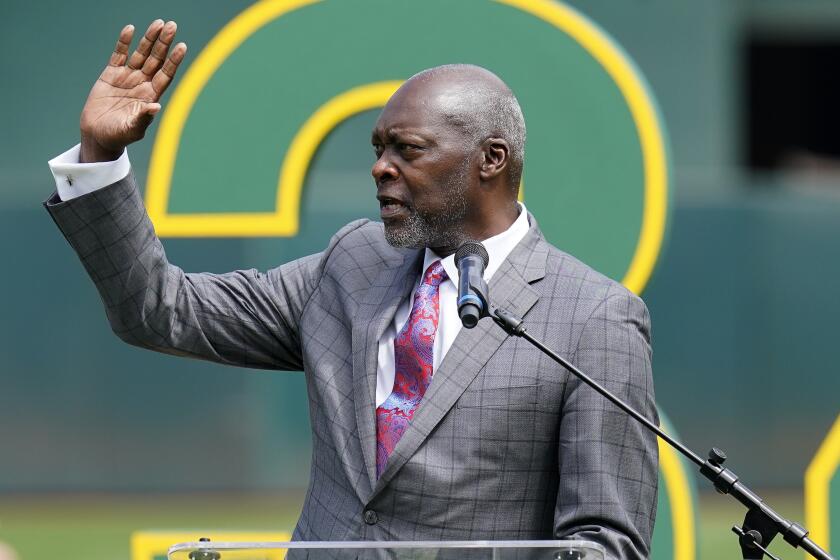

Oakland, the only major league city on the West Coast with a large Black community, is about to lose the A’s and that doesn’t sit well with former players.

That brings us, naturally, to Rob Manfred. It is part of the baseball commissioner’s job to persuade cities and counties and states that spending hundreds of millions of dollars in taxpayer money is a wise economic investment, despite the chorus of economists saying it is not.

Nevada has agreed to spend $380 million in taxpayer money to lure the Athletics from Oakland to Las Vegas. In a recent interview with Time, Manfred said he was aware of that chorus.

“There’s an equal number of scholars on the opposite side of that issue,” Manfred said.

No, scholars say, there are not.

“There are not two sides here,” said Holy Cross economics professor Victor Matheson, past president of the North American Assn. of Sports Economists.

Three scholars analyzed more than 130 studies on that issue and came to this conclusion: “Nearly all empirical studies find little to no tangible impacts of sports teams and facilities on local economic activity, and the level of venue subsidies typically provided far exceeds any economic benefits.”

In other words: Financially, it’s not worth it.

You don’t have to believe the economists, or slog through that academic language. In Nevada, the A’s consultant — not an economist — told the state legislature the same thing, in plain English.

“If you build a stadium in most places around the United States,” consultant Jeremy Aguero said, “it is going to have a negative economic impact.”

Las Vegas would be different, Aguero said, because the potential baseball audience for a ballpark on the Las Vegas Strip would include the 40 million tourists the city attracts each year. Economists are skeptical, but we’ll know in a decade.

Do baseball stadiums generate economic impact? Of course they do, starting with every ticket and hot dog and cap you buy. Teams hire consultants to estimate all that economic impact, and teams then use those estimates to lobby for public funding.

What those consultants generally do not do — and what economists say you must do — is consider net financial impact. If you spend $100 at the ballpark, but you might otherwise spend $75 on dinner and a show, economists say the economic impact would be $25. And yet, they say, too many consultants would classify that economic impact as $100.

“Committing this error in Econ 101 is a great way to earn an F on an assignment,” Kennesaw State economics professor J.C. Bradbury said. “It would be embarrassing if it wasn’t done so deliberately.”

On Tuesday, I asked Manfred what evidence he had to support his “equal number of scholars” comment, or whether he could better explain his comment.

“First of all, I think a lot of the scholarly work is overly broad,” Manfred said. “I think the economics surrounding baseball investments are different than in other sports.

“Number two, I think the best evidence is real life. Scholars are great. But I lived in Washington, D.C., for 15 years. Where Nationals Park sits was a neighborhood you would not visit, and I do not believe that it would look like it looks today absent that baseball facility.”

Matheson and Bradbury each said studies do break out the lack of economic impact for specific sports, including baseball. Although both were wary of using anecdotal evidence, Matheson did write this in 2018: “A concentrated entertainment district created by a stadium, such as San Diego’s Gaslamp District or Denver’s LoDo, may increase economic activity by creating a focused attraction for tourists and visitors from outside the city.”

The players’ union has no say in whether the Oakland A’s move to Las Vegas, but MLB must negotiate the working conditions with the union.

Said Manfred: “Economists are great. They can think what they want. My view on that topic is from being around it and watching what has happened with baseball facilities for years and years.”

Matheson acknowledged that cities might want a team for reasons that are not purely economic: diversity of entertainment, quality of life, civic pride and so forth. In studies, he said, economists have quantified those benefits and found the subsidies used to justify them wildly out of line.

Bradbury suggested this standard: Nevada has about 3.2 million residents. Would Nevadans agree that each resident should pay $118.75 to lure the A’s?

The Nevada teachers’ union is trying to put that question before the voters. That appears unlikely but, in a campaign, what Matheson says would make quite the populist talking point: “Every dollar that goes into subsidizing a stadium goes into the pocket of a billionaire owner and out of the pocket of an average taxpayer.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.