Why have the Dodgers been so slow to honor Glenn Burke, MLB’s first openly gay player?

- Share via

On a Florida beach vacation with my family last week, I was under orders not to check my phone too much.

But I sneaked a peak last Friday afternoon and was heartened to see a tweet from a Bay Area sportswriter sharing the news that the Oakland A’s have renamed their annual Pride Night after Glenn Burke, the former Berkeley High baseball and basketball standout who went on to become the first openly gay Major League Baseball player with the Dodgers and A’s in the late 1970s.

This is a well-deserved posthumous honor for Burke, recognizing his unique contribution to the game and the enduring significance of his story. But as appropriate it is for the A’s to celebrate Burke, it also raises the question: Why didn’t the Dodgers do it first?

The Dodgers selected Burke in the 1972 MLB draft. The Dodgers invested in his development and a minor league career in which he hit above .300 four times and set stolen base records in two leagues. Longtime Dodgers player and coach Junior Gilliam shared the organization’s high opinion of their speedy and powerfully built outfield prospect: Burke had the potential, Gilliam said, to be the next Willie Mays.

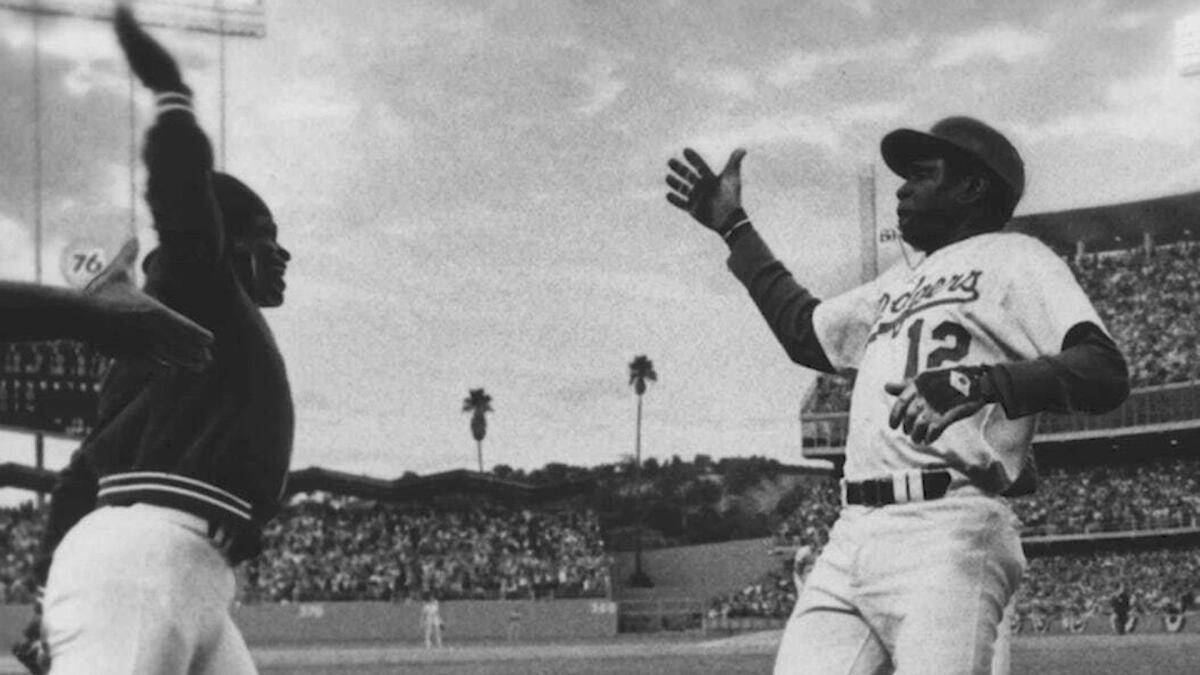

Burke would not come close to living up to those lofty expectations, but he did start two games for the Big Blue Wrecking Crew in the 1977 National League Championship Series against the Phillies, and started Game 1 of the ’77 World Series at Yankee Stadium. He was a popular player in the clubhouse at a time when the roster was loaded with All-Stars. He is even credited with inventing the high-five as a Dodger.

As millionaire owners and millionaire players negotiate the distribution of many hundreds of millions of dollars, Glenn Burke (“When Glory Has Soured,” Aug. 30) suffers on the streets of San Francisco, enduring the horrifying and lonely torment of AIDS.

The first openly gay major leaguer was a charismatic reserve on a great Dodgers team, and yet the franchise rarely acknowledges him. Searching Twitter, I can find only one time they’ve mentioned his name, an Oct. 2012 Tweet about the historic high-five. A search of his name on the Dodgers website turns up blank. When Burke was experiencing homelessness while dying of AIDS in the early 1990s, it was the A’s, and not the Dodgers, who offered assistance.

In researching my biography of Burke, “Singled Out,” I got the sense that this was a subject many Dodgers players and executives, past and present, preferred not to touch. The team’s marketing department acknowledged receiving but did not respond to several questions for this column, including questions asking for any examples of the team’s acknowledgment of Burke that I may have missed.

Even looking at the team’s long history of well-executed Pride Nights and support for LGBTQ organizations and causes, there has been something conspicuously missing: a meaningful connection to Glenn Burke and the team’s place in gay history. The A’s invited Glenn’s brother, Sidney, to throw out a first pitch six years ago, and their Pride event tonight will raise money for the Glenn Burke Wellness Clinic at the Oakland LGBTQ Community Center. (The Dodgers said they had “nothing special planned” to recognize Burke at their Pride Night tonight, “but that doesn’t rule out something in more in future years.”) I don’t know why the Dodgers haven’t made more of their connection to Burke, but there are elements of his experience the team might rather forget.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

Following the 1977 season, Dodger Vice President Al Campanis offered Burke a hefty bonus if he’d get married.

“To a woman?” Burke replied, declining the bribe and setting the wheels in motion for his trade to Oakland in May 1978.

I’ve wondered when the franchise’s attitude toward Burke might change. But with last week’s announcement, the A’s have beaten the Dodgers to the punch in at least one highly visible way, 43 years after Burke played his last game for the Dodgers and 26 years after his death.

Your clips are strong and you’re a good writer, but I can’t send a “faggot” in a locker room.

The situation reminds me of an interview I conducted with David Williams, the late African American athletic director at Vanderbilt University, when I was writing a biography of Perry Wallace (“Strong Inside”), the first Black basketball player in SEC history. Wallace attended Vanderbilt in the late 1960s and in many ways found his own campus to be as inhospitable as road trips to Mississippi and Alabama. Williams had arrived at Vanderbilt three decades after Wallace made history there and was stunned to learn the Nashville university had done nothing to honor him: “You mean to tell me the Jackie Robinson of the SEC played here and you’re not waving banners and shouting about it?” Williams recalled telling university administrators.

At Williams’ urging, that changed. Today there are two scholarships named after Wallace and an annual courage award in his name. His No. 25 jersey hangs from the rafters at Memorial Gymnasium, an oil portrait is placed prominently in an engineering building, and Perry Wallace Way winds its way through the Vanderbilt campus.

In the decade before his death in 2017, Wallace was invited back to campus many times to tell his story to new generations of students and to receive these deserved, even if late-in-coming, accolades. I asked him what it felt like to be honored by the same institution that had ignored him for so long. “Reconciliation without the truth is just acting,” he said. “But when the truth is present, real change and healing can occur.”

Vanderbilt ultimately decided to reconcile with Wallace in a truthful way, requiring first-year students to read “Strong Inside” two years in a row. Rather than hide from a painful era in the school’s history, administrators embraced it, challenging new students to learn about racism in the university’s past and to discuss how it affected people — and how they’d combat it — on campus today. The conversations were powerful.

“Reconciliation without the truth is just acting, but when the truth is present, real change and healing can occur.”

— Perry Wallace

I simply wonder why the Dodgers have not taken a similar approach. I’ve got no ax to grind. I love the uniforms and the passion of the fans. My grandfather grew up in Brooklyn and was a fan. As a Vanderbilt guy, I root for Walker Buehler and David Price, and Mookie Betts is a Nashville hero too. And the Dodgers certainly deserve credit for their long history of reaching out to gay fans, while the Texas Rangers, for example, have never held a Pride Night.

But it appears that the Dodgers have not yet reached the reconciliation point with Glenn Burke’s story, truthful or otherwise. This is a shame, because as one of the most high-profile organizations in all of sports, the Dodgers could effect change, in a game that needs it, if they led an honest conversation on Burke’s experience as a gay major leaguer. There are no openly gay players in the Major Leagues today.

David Williams told me something else when I asked him about squaring his commitment to progress with the racism in his university’s past. People won’t forget but they will forgive past transgressions, he said, if they can see you’re making honest and meaningful strides toward progress; they care more about what you’re doing right now than what your predecessors did wrong in the past. Just ask the A’s. Manager Billy Martin told sportswriters he wasn’t going to let a f— like Glenn “contaminate” his team and banished him to the minors, never to return. Yet the team’s decision to honor Burke is celebrated.

The first openly gay Major League player was a Dodger. It’s time for the Dodgers to take ownership of the homophobia that prematurely ended Glenn Burke’s days in Los Angeles so that the organization can move beyond it, stake its claim to history by centering Burke’s experience, and lead the way for LGBTQ rights in baseball. There would be no more credible voice.

Bestselling author Andrew Maraniss writes sports and history-related nonfiction for teens and adults. He lives in Nashville and is on Twitter @trublu24. “Singled Out: The True Story of Glenn Burke,” was published by Philomel Books on March 2.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.