Column: The road from Spencer Haywood to LeBron to the Lakers’ 17th NBA championship

- Share via

The NBA season had to end this way — with this Laker team winning this championship, led by this GOAT. An unprecedented time presented immense challenges that extended far beyond the court. But it had to be this way. After all, heroes are forged by the most arduous journeys, and the Lakers’ road to this championship was more draining than any of the 16 previous ones.

It would, however, be a mistake to begin the retelling of this season’s story with the bubble, although it is a major character. The mental fortitude it took for players and coaches to manage feelings of isolation and fear of contracting a potentially deadly virus cannot be overstated.

Similarly, it would be incomplete to start this story on Jan. 26, the day our hearts were crushed by the deaths of Kobe and Gianna Bryant and seven others in a helicopter crash, though their presence was definitely felt every step of the way.

Nor is April 9, 2019, the best point to pick up this remarkable tale. That was the day Magic Johnson abruptly quit as team president, leaving Jeanie Buss open to ridicule as well as calls to sell the team.

The story of the Lakers winning the 2020 NBA championship cannot be told without the backdrop of the social justice movement that was, as much the pursuit of a title, the raison d’etre for the bubble. And that story starts with the day in 1964 that Spencer Haywood went to jail.

The Lakers and many other NBA players used their time in Orlando, Fla., for activism to fight social injustice and seek ways to continue advocacy.

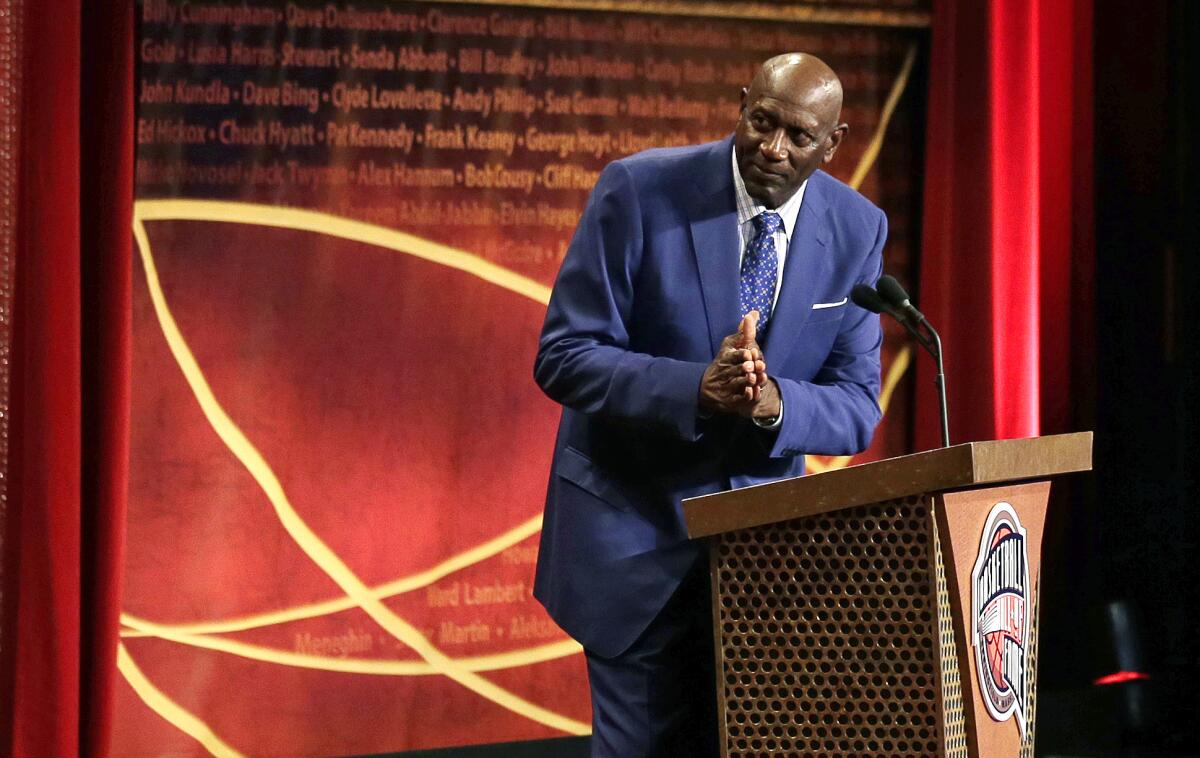

A child of the Deep South, Haywood, a 2015 Hall of Fame inductee, has said that his only goal growing up was to be the best cotton picker in all of Mississippi. That sentiment reveals both the extreme poverty of his youth as well as his drive to be the best, regardless of his circumstances.

When Haywood was 13, he was his family’s primary breadwinner, earning $4 a day for picking 200 pounds of cotton. The following year, he began working in a country club, where a white man accused Haywood of trying to steal a quarter before slapping him. This led to an altercation and Haywood’s arrest.

Marc Spears and Gary Washburn tell this story beautifully in their recently published book, “The Spencer Haywood Rule.” “One of the things the farmers did down South in my neck of the woods,” Haywood says in the book, “if you were growing big and strong, they would mess you up some kind of way to where you can get attacked and go to jail for two or three months and then you are relegated to that farm. And that’s slavery forever.”

His mother, fearing for his safety, got her son out of jail the next day, and the family bought a bus ticket for Spencer to live with his brother in Chicago. As he grew as a basketball player, so did his notoriety, and he became a key member of the 1968 Olympic team that won the gold medal.

Of course, 1968 is the seminal year in the history of the Black athlete, the year upon which the conversation and strife of this year finds its greatest inspiration. Lew Alcindor boycotted those Games because of how Blacks were being treated in the United States just as today’s players suspended postseason play this year after an unarmed Jacob Blake was shot in the back multiple times by police in Kenosha, Wis. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. weighed in on Black athletes using their platform to protest then, former President Obama weighed in now. It’s all so cyclical. Sadly.

Haywood was watching TV in the Olympic village when he saw Tommy Smith and John Carlos standing on the medal podium with their fists clenched and arms raised. And he saw up close how they were treated in the aftermath.

It is the hope of Lakers star LeBron James that NBA players continue to speak out about social injustice and police brutality once the season is over.

“It was so horrible,” Haywood said in the book. “They were being treated like pieces of s—. It was so horrible — and it reminded me so much of when I was 13 and 14 in Mississippi. It was the same s—.”

Yes, things have changed, and no, things have not. You can draw a through line from the time when a 13-year-old Spencer Haywood was picking cotton in the Mississippi fields to James holding the Larry O’Brien Trophy. Different images, same systemic barriers to quality and justice. The Black community continues to trail its white counterpart by uncomfortably high socioeconomic margins. Prison demographics are relatively unmoved. COVID-19 exposed a healthcare chasm that has put Black and brown lives at significantly greater risk.

This is why key Lakers players such as Dwight Howard and Avery Bradley openly questioned whether returning to play this summer, amid protests for racial justice, was prudent. They didn’t want to be what sports has always been — a distraction. They didn’t want the names of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor to be run off the networks by basketball highlights. And thanks to the manner in which the NBA presented the games, they were not.

Yes, this Lakers championship was won in a bubble, but it did not take place in a vacuum. The title both part of the continuation of Lakers excellence dating back to George Mikan as well as an extension of the legacy built by men such as Carlos, Smith, Alcindor, Muhammad Ali and Haywood.

When the NBA tried to keep him out of the league because of an arbitrary “four-year rule” tacitly designed to keep the league from becoming too Black, Haywood didn’t shut up and dribble. He filed an antitrust suit against the NBA, which like Ali’s before him, made its way to the Supreme Court and was successful. Ironically, Haywood’s most vocal NBA opponent was Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke, who, according to Haywood, was concerned the country wouldn’t support a league dominated by Black men.

All of these events, these seemingly disconnected moments in American history, are woven together in Lakers folklore — Magic begat Kobe who begat LeBron. And all the championships and celebrations they represent was made possible in no small part to Spencer Haywood. How sweet it must have been for him to win a ring as a member of Jerry Buss’s Lakers in 1980, after the grief Cooke — who had sold the franchise only a year earlier — gave him for simply trying to make a better life himself and his family.

‘Never fear, Magic is here’: On May 16, 1980, with the Cap sidelined with an ankle injury, Magic Johnson launched a decade of Lakers ‘Showtime’ dominance.

And this is how I will tell my grandchildren about the story of the 2020 NBA champions. Not just with January’s tragedy or March’s closures, but rather an all-encompassing look at this remarkable team, which traces back to a 13-year-old Black boy who wanted to be the best cotton picker in Mississippi. The players not only survived the mental and physical toll of restarting a season far from family, friends and fans, but they also used their platforms to continue the work begun by the giants on whose shoulders they stand.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.