Coronavirus is retiring the handshake. Here’s why that could change sports forever

- Share via

Blood streams in dark rivulets down the side of one man’s face. The other man has a blackened eye as he extends his hand in congratulations or, perhaps, empathy.

The year is 1952 and two hockey teams have just finished a brutal semifinal series. A bloodied Maurice “Rocket” Richard, star of the victorious Montreal Canadiens, looks wobbly standing at center ice for the “handshake line” that has followed every NHL playoff for decades.

The goalie of the losing Boston Bruins, a similarly battered “Sugar Jim” Henry, leans slightly forward as they meet. There is something emotional about his affect, an old photograph of the moment capturing everything you need to know about this ritual of sport.

Boxers touch gloves before fighting and football players greet each other at the coin flip. In tennis, golf and soccer, competitors wait until after the game. Sportsmanship only begins to explain a custom that endures regardless of animosity or even violence on the field of play.

“It’s rooted in our primate psychology,” said David Givens, an anthropologist at Gonzaga University’s Center for Nonverbal Studies. “Primates, especially chimps and gorillas, will reach out and touch each other’s hands, before aggression and after aggression.”

Evolution and neuromuscular circuitry notwithstanding, the handshake has come under attack — in sport and throughout society — from COVID-19. Common etiquette has been rebranded as a vector for spreading infection.

“When you consider the sweat factor, in just two months shaking hands has become unthinkable,” said Pam Shriver, among the greatest doubles players in tennis history and an ESPN commentator. “It’s done and I don’t think it’s going to come back.”

The question is, might sports be losing something important?

::

The physical act has a geometry all its own.

The palm should be perpendicular to the floor, facing neither downward in a show of dominance nor upward in meekness. Contact should be diagonal, the web of skin below each thumb meeting in symmetry. Shake two to five times, no more or less.

The result of this equation can be far greater than the sum of its parts.

Nelson Mandela helped cement his fledgling presidency in post-apartheid South Africa by way of a famous handshake and pat on the shoulder with a white national rugby star, Francois Pienaar, at the 1995 World Cup championship.

In 1963, the all-white Mississippi State basketball squad sneaked out of town, defying a segregationist history to play in the NCAA tournament against a Loyola of Chicago squad with black players on the roster. The teams shook hands before tipoff.

“It was amazing, so many camera flashes,” Joe Dan Gold, captain of that Mississippi State team, told the Clarion-Ledger of Jackson, Miss., in 2011. “That’s when it hit me, this was more than a game. This was history.”

Flouting the ritual can mean trouble.

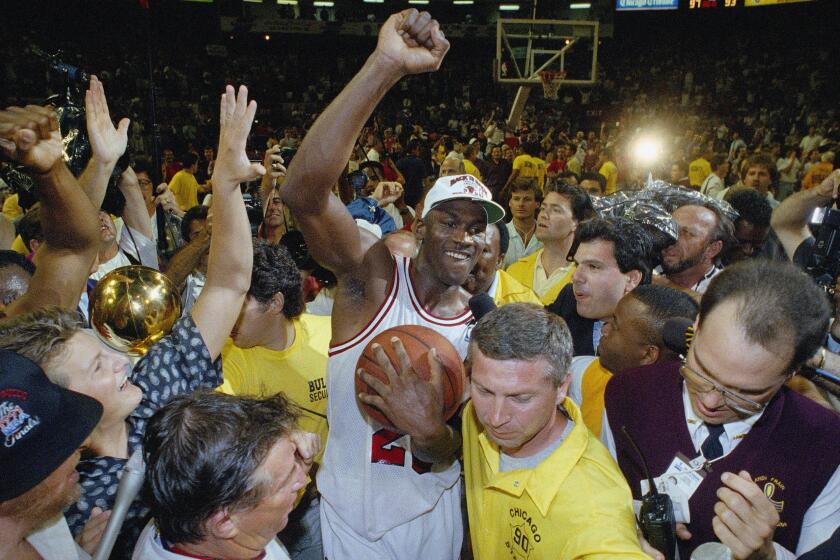

The Detroit Pistons walked off the court after a 1991 NBA conference semifinal loss without acknowledging Michael Jordan and the victorious Chicago Bulls. Recently asked about public backlash, which persists to this day, former Pistons star Isiah Thomas seemed to have second thoughts.

“Knowing what we know now, in the aftermath of what took place, I think all of us would have stopped to say, ‘Hey congratulations,’” he told ESPN’s “The Last Dance” documentary.

To which Jordan responded: “There’s no way you can convince me he wasn’t a [jerk].”

Coverage of ESPN’s “The Last Dance” series, featuring behind-the-scenes stories about Michael Jordan, the Chicago Bulls, Kobe Bryant, Carmen Electra and more.

After a 2011 NFL game, coach Jim Harbaugh of the San Francisco 49ers got a little too enthusiastic about winning, bouncing across the field toward his counterpart with the Detroit Lions. The resulting handshake was more of a stab, followed by a rough slap on the back, triggering a scuffle between the teams.

Detroit coach Jim Schwartz complained to reporters: “I went to shake an opponent coach’s hand and obviously you win a game like that, you’re excited. But there’s a protocol that goes with this league.”

After a rash of postgame fights in 2013, Kentucky high school officials issued a directive that initially appeared to ban handshakes. A Southern California league had taken similar action years earlier. Officials soon backpedaled in both cases.

As a philosophy professor at Tarleton State University in Texas, Craig Clifford sees the gesture as formative for young players, especially when emotions run high.

“You can’t have a good game without a good opponent, whether you like your opponent or not,” said Clifford, co-author of the book “Sport and Character.” He added: “It’s not about being a nice person. It’s saying, ‘I’m going to give you respect because you’re making it possible for me to play this game.’”

::

In ancient times, strangers greeted each other by extending an open palm to show they had no weapon. The up-and-down motion of the early handshake? It might have been a way to jostle loose any knives tucked into sleeves.

Clasping hands transformed into a sign of good faith by the 9th century BC, when a stone bas-relief shows Assyrian ruler Shalmaneser III sealing an alliance with a Babylonian counterpart. Much later, in the 17th century, Quakers considered it an egalitarian alternative to formal bowing or hat-tipping.

Whatever the motive, anthropologist Givens sees deeply instinctual behavior.

Touch ranks among the oldest human senses, behind smell, the fingers laden with sensitive nerve endings connected to modules of the brain.

Skin-to-skin contact has been shown to signal the adrenal glands, limiting production of cortisol, a stress-inducing hormone, in both parents and their babies. Researchers suspect the handshake may trigger a similar response, which would be relevant to athletics.

“There is the initial fear before you get in the ring or on the field, a lot of athletes talk about the fear,” Givens said. “There is the adrenaline aspect to sport and you can partially counteract that by reaching out, which puts you a little at ease.”

The hands are linked to another hormone — noradrenaline — that drives anger. In an aggressive state, humans tend to stand taller and orient their palms downward — picture a coach rising up and smacking the lectern in a team meeting.

Too much emotion can be counterproductive to clear thinking and execution on the field. So, like a dog crouching when it encounters another dog, even a vicious linebacker might be subconsciously tempering his anxiety when meeting with opposing team captains at midfield before kickoff.

And what about tennis players approaching the net after a match? It might be a way to soothe roiling biochemistry, to get both sides feeling better after heated competition.

“The brain seems to know how to handle these things and how to mitigate by tactile cues,” Givens said. “Shaking hands is a way to lessen the effect.”

Boxers started doing this sort of thing more than 150 years ago. When the Marquess of Queensberry mandated gloves in 1867, fighters became an unwitting precursor to modern times, wearing personal protection and bumping fists.

In hockey, the handshake dates to at least 1908, when teams in an all-star charity game reportedly lined up. The formality took hold by the 1930s, becoming inviolable.

“As far back as when I was a kid, there was so much respect for the game and what we did,” said Luc Robitaille, a former Kings star and now team president.

“We had to dress up for tournaments, nice pants, no jeans,” he said. “Then, after we played, we shook everyone’s hand. It was just what we did and we never thought of any other way.”

::

The coronavirus spreads by way of respiratory droplets, mostly through coughs and sneezes. It can be transmitted indirectly if an infected person makes hand-to-hand contact with someone who touches their nose, mouth or eyes.

There is something ironic in worrying about this when it comes to games such as football and basketball, where bodies often collide, but a 2014 study published in the American Journal of Infection Control found that shaking hands can transmit nearly twice as many bacteria as high-fiving and about 10 times more than bumping fists.

“It is unlikely that a no-contact greeting could supplant the handshake,” the authors wrote. “However, for the sake of improving public health we encourage further adoption of the fist bump as a simple, free and more hygienic alternative.”

It has taken hundreds of thousands of deaths from COVID-19 around the globe to reinforce this notion.

Even before sporting events were canceled because of the outbreak, the NBA advised players to avoid high-fives with the crowd and Major League Baseball warned against accepting pens from fans to sign autographs. Handshakes between competitors were suspended in soccer games, cricket matches and golf tournaments around the world.

“It’s just one thing that should change and probably will change,” University of Kentucky basketball coach John Calipari said on the “BBN Live” show. “The game ends, you point. ‘See you after.’ Call the guy on the phone. These kids stay in touch anyway.”

Soccer referee Katja Koroleva is on the frontline in battle against COVID-19, as a physician assistant.

If the custom fades — and not everyone thinks it will — experts hope something else will take its place.

Contact might not be required, the mere orientation of the hand conveying fundamental information. Think of a friend raising his hand in greeting or people turning their palms upward in exasperation or confusion.

So a simple nod and wave might suffice, or maybe the Hindu greeting of namaste, with hands pressed together as in prayer. When the PGA Tour returns with a tournament next month, officials have asked players to consider “a tip of the cap or an air fist bump or something from a distance.”

“You wouldn’t get the full effect of the actual touch,” Givens said. “But the recognition of another’s physical presence, you’re taking them seriously.”

Much like Robitaille, Shriver recalled learning about the postgame handshake as a youngster. “You watched the pros do it on TV,” she said. “You saw your parents at the club.” If the thought of clasping hands now gives her pause — the sweat factor — she suspects that sports will adapt.

For years, players have devised intricate, ever-evolving handshakes and high-fives. The custom could persist, if only from a distance.

“Each sport has to find a gesture of sportsmanship,” Shriver said. “It’s going to be interesting to see what happens.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.