- Share via

TOKYO — Olympic divers look at the pool a little differently than the rest of us. They see angles and molecular attractions and cohesive forces. They recognize the unfortunate circumstances that can make entering the water feel like “slamming into the floor.”

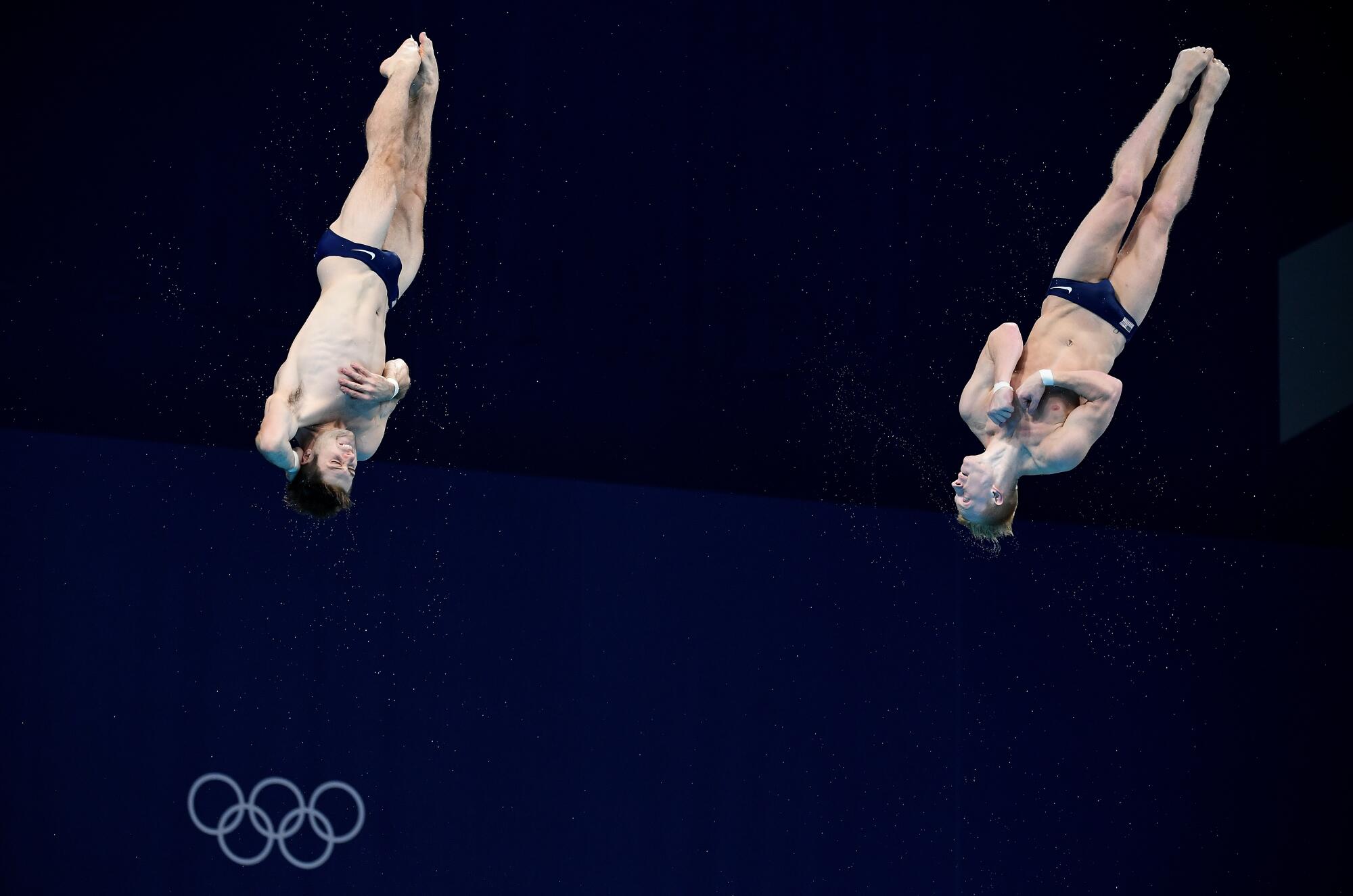

This is the science of their sport. A human body plummeting from a 10-meter platform, head-first, reaching speeds of approximately 32 miles an hour. The sudden jolt from water’s relatively high surface tension of 72 millinewtons per meter.

“People have no idea,” says Kassidy Cook, a veteran of the U.S. national team and past Olympian. “When you hit the water, it’s as hard as concrete for a split-second before you break through.”

So, as the diving competition proceeds at the Summer Games over the next week, the competitors will look graceful on television, their flips and spins both dazzling and elegant. But know that many of them have long histories of pain.

Broken wrists and dislocated shoulders. Twisted necks and elbows and ruptured eardrums. Concussions are relatively common, as are pulmonary contusions in which the force of impact bruises the lungs.

News, results and features from The Times’ team of 12 reporters who covered the Tokyo Olympic Games in the summer of 2021.

Each dive sends shock waves through muscle, ligament and bone. The constant pounding is not unlike being an offensive lineman in the NFL.

“This is a contact sport,” says John Locke, the medical director for USA Diving. “It puts a lot of negative forces on your body that you have to overcome to be an Olympian.”

Competing in Tokyo with a screw in his surgically repaired wrist, patellar tendinitis in both knees and lower back issues, U.S. team member Brandon Loschiavo explains: “Diving beats you up.”

The competition in Tokyo will continue with the women’s 3-meter springboard as individual events begin Friday. Most of the attention will focus on what we can see, divers launching themselves upward and outward from the platform or board, generating a forward velocity that carries them in a gradual arc toward the water.

The all-important rotation must begin immediately if they are to execute four or more flips in just 1½ seconds of air time. All the way down, they must be aware of their body position in space while keeping an eye on the fast-approaching water in hopes of entering as straight as possible.

“Knee-buckle is one of the worst things that can happen. That happened to me a lot when I started. One of those times I tore my ACL [knee ligament].”

— Krysta Palmer, U.S. diver

The other part — the pain — begins before they even get wet.

The 10-meter event, the equivalent of jumping off a three-story building, can cause repetitive strain injuries from repeatedly pushing off a concrete platform. Three-meter divers must deal with the whip-like pushback of the springboard.

“Knee-buckle is one of the worst things that can happen,” says Krysta Palmer, who finished eighth with Alison Gibson in the 3-meter synchronized event. “That happened to me a lot when I started. One of those times I tore my ACL” knee ligament.

Though springboard divers start from a lower height, they make up much of that difference when vaulting airborne from the board, so their speed at impact is not much less.

All divers must ultimately deal with the fact that molecules along the surface of the water cohere more strongly than those below. This resistance varies slightly with each pool, influenced by temperature, filtering and draining.

Skintight bathing suits provide no defense, though athletes often tape their wrists and hands. In the blink of an eye, their bodies must displace gallons and gallons of water upon entry.

“Gravity brings you down and the water is stopping you all of a sudden,” says Dr. Nathaniel Jones, an associate professor of orthopedic surgery who works with divers at Loyola University Medical Center in Illinois. “The body is quickly decelerating on impact, so we talk about the ‘kinetic chain.’”

The goal is to distribute the shock throughout this “chain” of hands, wrists, elbows and shoulders.

The process requires entering the water at a perpendicular angle, with arms outstretched, hands overlapped and palms facing the water. The diver is, essentially, trying to punch a hole in the surface and slip as cleanly as possible through a small opening.

“If you miss the hand grab, all the water pressure goes through your triceps,” says British diver Noah Williams, explaining how he once tore that muscle. “It’s not fun but it comes with the sport.”

A perfect entry is called a “rip” because it sounds like tearing paper. Loschiavo describes it as “cutting through warm butter.” For judges, it means a higher score; for athletes it means escaping some of the sting.

But avoiding pain is not always possible as elite divers perform a dizzying array of pikes, tucks and somersaults.

Rotating too little or too much, even by a few degrees, will cause the body to hit the water at an awkward angle. Any sort of twist or imbalance can put stress on ball-and-socket joints.

If there is what Jones calls a “weak link” — a muscle not quite as strong as the others — injury will find its way there.

The risks have steadily increased as the sport has evolved, requiring Olympians to attempt dives with harder degrees of difficulty.

“Have you ever done a belly flop off the side of a pool?” Cook asks. “Imagine doing that from 15 feet higher while doing multiple flips and how bad would that hurt.”

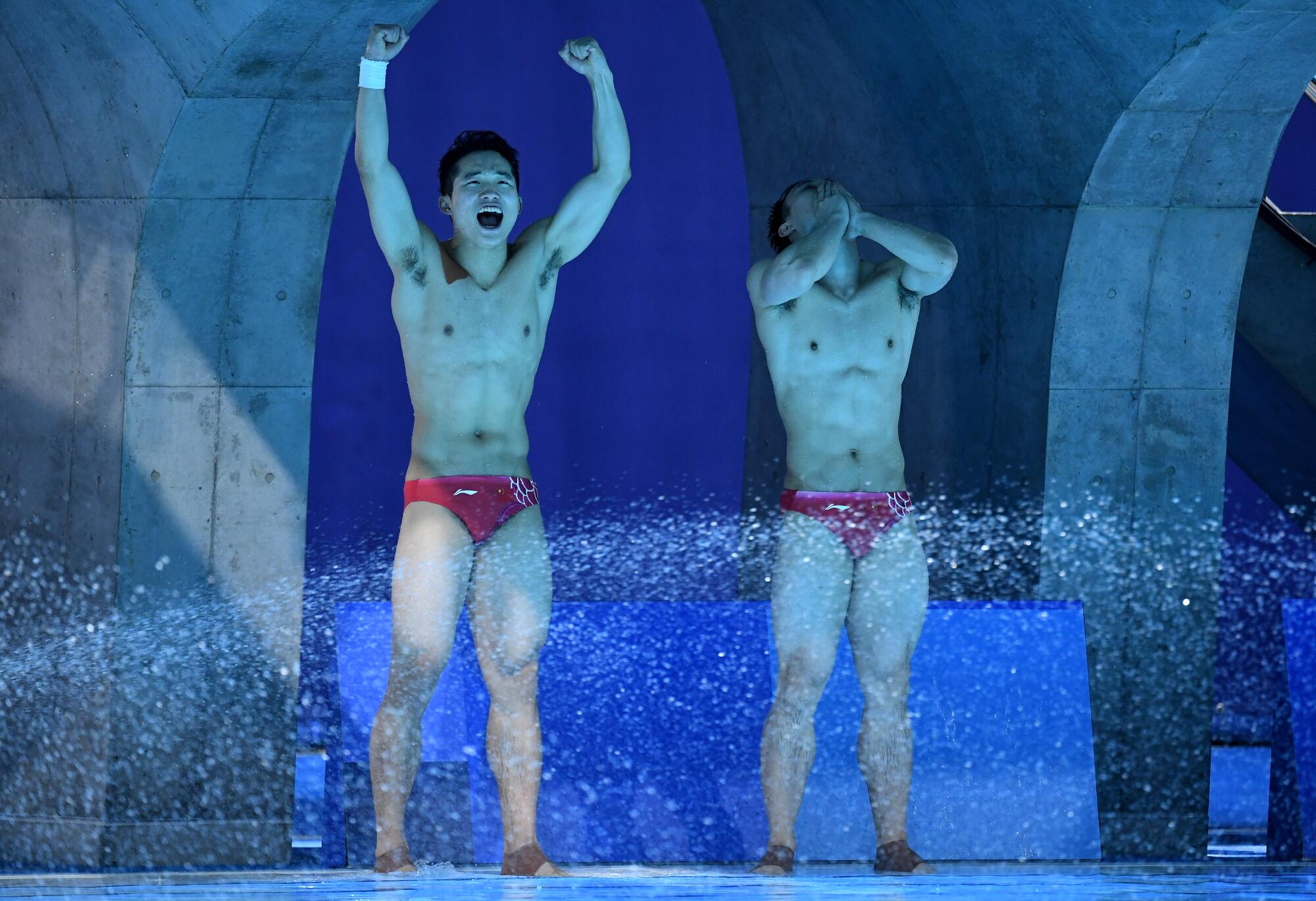

Locke marvels at how divers overcome their fear after getting injured. He says: “They just have to get back out there, hit the water again.”

The 26-year-old Cook competed at the U.S. trials last month with a stress fracture in her shoulder — every dive inducing a wince of pain — and barely missed making her second Olympic team. At the same meet, Steele Johnson, a silver medalist at the Rio de Janeiro Games, had to withdraw with a foot so badly injured he could barely walk across the pool deck.

“I’ve been through two failed surgeries,” he told NBC Sports. “At some point you’ve got to make the wise decision and step back and focus on your health more than Olympic glory.”

There’s another thing we cannot see from the stands or watching on television. It involves boosting the judges’ score by minimizing splash.

Just below the surface, divers execute what they call a “swim” or “save.” Spreading their arms and somersaulting either forward or backward underwater, they can foster the illusion of a vertical entry and pull extra water down that hole with them in a maneuver that stresses lower back muscles and hip flexors.

Added to all of this are overuse injuries from thousands of hours of practice over the span of a career. Canadian diver Caeli McKay arrived in Tokyo with an ankle injury that hampered her preparation: “In training I can do only 25 dives a day, so I’m making every one of them count.”

Top competitors try to protect themselves by strengthening shoulders, arms and core muscles in the weight room. They stretch constantly to remain flexible. Practicing technique off a trampoline and landing on a foam pad, known as dry-land training, also helps.

“It’s such a repetition sport,” Loschiavo says.

Almost everyone gets hurt eventually — it’s a fact of competing at a high level. So the final piece of the puzzle for those who want to make the Olympics is mental preparation.

The 59 or so steps up to the 10-meter platform, the tense moments perched at the edge with arms extended, leave plenty of time for doubt.

“You have it in the back of your head, this dive hurt me before,” Cook says. “What if I hurt myself again?”

Visualization can ease anxiety. Divers build confidence with those dry-land workouts and weight training. They study the science and find ways to get past the hurt.

“Whenever people hear about the injuries, they say ‘Really? From diving?’” Cook says. “They don’t know how cruel the water can be.”

It is the part of this sport we don’t see.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.