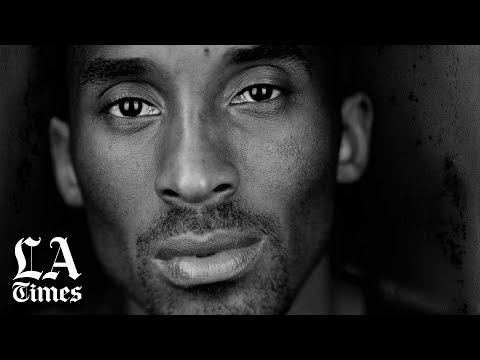

Column: No athlete represented Los Angeles quite like Kobe Bryant

L.A. mourns the death of Lakers legend Kobe Bryant.

- Share via

He was named after premium beef from Japan. He spent most of his childhood in Italy. He was a high school basketball legend in Philadelphia.

And he was all Los Angeles.

Kobe Bryant came here a 17-year-old boy, still not a legal adult when he was acquired by the Lakers on draft day in 1996. In a two-decade career played entirely in this city, he scaled the greatest of athletic peaks and was tarnished by the worst of personal scandals. He was beloved, reviled and, in the end, revered. He became a father here, retired here, continued to live here and started businesses here.

Los Angeles watched him grow up. Los Angeles watched him stumble. Los Angeles watched him get back up. Los Angeles watched him transition into middle age.

News of Bryant’s death on Sunday sent shockwaves everywhere, but nowhere more than here, his home.

Regardless of the complicated feelings that remain over the sexual assault charge against him that was dropped after an out-of-court settlement, Bryant was undeniably the athlete who most represented this city over the last 30 years.

Kobe Bryant was our childhood hero, our adult icon. It seems impossible to believe he has died at age 41.

Los Angeles now mourns the loss of its child.

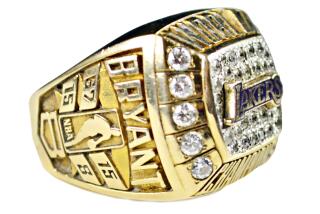

He won five championships, but was defined by more than the rings and awards he collected. He was the physical embodiment of a philosophy that became this city’s unofficial ethos.

He called this relentless pursuit of excellence the “Mamba Mentality.”

Bryant was the opposite of Magic Johnson, the Lakers superstar of the previous generation. Johnson, who also spent his entire career with the Lakers, was a pleaser. He was gregarious. He was a spectacular passer. He radiated joy on the court.

Bryant came across more as an obsessive, like Michael Jordan without the deceptively warm smile. He snarled. He didn’t compromise.

As an 18-year-old rookie, he had the audacity to fire four airballs down the stretch of a playoff elimination game loss to the Utah Jazz.

The persistence and individuality he showed became trademarks to which this city of transplants and immigrants related. His triumphs became symbolic of its ambitions.

By leading the Lakers to the NBA championship in 2000, Bryant and Shaquille O’Neal restored the pride of Los Angeles, which hadn’t claimed a major championship since the Dodgers won the 1988 World Series.

By also winning championships in 2001 and 2002, Bryant and O’Neal recalibrated the city’s expectations. They made titles feel as if they were civic birthrights. Since then, any team finishing with anything less than a championship has been considered a failure. The Dodgers have felt the ramifications of that in recent years. LeBron James will, too, if the Lakers fail to win it all this season.

When Magic Johnson won championships with the Showtime Lakers, the Dodgers were still Los Angeles’ signature franchise. Bryant and O’Neal changed that, enough to where the Dodgers couldn’t reclaim the city even as their recent resurgence coincided with one of the worst periods in Lakers history.

Through it all, Bryant remained an unapologetic original, which ultimately broke up the dynasty. He clashed with the easy-going and sensitive O’Neal and nearly signed with the Clippers. The Lakers traded O’Neal. Bryant stayed with the Lakers.

O’Neal was the first to win a championship after the breakup, capturing a title with the Miami Heat in 2006.

Bryant persevered. His first trip to the NBA Finals without O’Neal resulted in a defeat to the Boston Celtics. Redemption came in the back-to-back championships in 2009 and 2010.

Just as Bryant willed his teams to victory, he willed his way back into the public’s good graces. His triumphs virtually erased the rape allegation from civic memory — or at least made it rarely mentioned.

Bryant remained an admired figure even as injuries diminished his once-formidable talents. There were occasional reminders of the warrior within. He once stayed in a game to sink two free throws after suffering a torn Achilles tendon. In the last NBA game he played, at the age of 37, he scored 60 points in a win over the Jazz.

In retirement, he won an Academy Award for an animated short film he wrote and narrated, as if there could be anything more Los Angeles than that.

To the end, in good times and in bad, he was a portrait of the city. He still is.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.