High school softball players find solace in being able to wear jewelry during games

- Share via

A couple days after her mother died, when everything felt unreal and very frustrating, Jordyn Lawhon put on the necklace for the first time.

It is a simple heart-shaped token, shimmering silver against her gray Villa Park uniform. It was her mother’s piece of jewelry. Lawhon would always plead to wear it, and her mom said no, because there was a tiny, tiny knot in the chain. No messing it up.

Within a two-week whirlwind in January 2022, the woman who kept her grounded went from perfectly fine to sick with COVID-19 to whisked away by an ambulance. It was the last time the family saw her. A couple days later, Lawhon’s dad used a pair of tweezers to fix the knot.

Lawhon put it on, and never took it off. Not until spring, when umpires would spot the shortstop trying to tuck it under her jersey and order her to take it off. Such were the rules for high school athletics.

“I got so mad about it,” Lawhon remembered.

This spring, though, a vote by the National Federation of State High School Assns. made it legal for high school softball players across the nation to wear jewelry. The impact is everywhere: the phrase “look good, play good” is ingrained in softball culture, multiple coaches said, and jewelry is a chance for high school players to feel comfortable in their individuality.

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The freedom carries a deeper, poignant impact for many: the chance to carry a memento of a loved one onto the diamond. A comfort in moments of anxiety.

“That’s why,” Lawhon said of her mother’s necklace, “she’s always going to be super close to my heart.”

Ritual is inherent in baseball and softball, baked into every stride to the batter’s box, every warmup between innings. And jewelry, Cerritos Gahr’s Amarie Allen said, is a simple extension of that ritual, providing a sense of stability unique to each athlete.

“The girls, now, are able to be themselves,” said Orange El Modena coach Robert Calderon.

When Allen turned 15 in her sophomore year, her mother gave her a gold necklace with a charm of the letter “R.” It was a memento honoring her father, Rady, who’d died a couple years earlier from a heart attack. He was Allen’s best friend and safe place; when anxiety seized her on and off the field, he’d help her breathe.

In the summer, Allen had surgery, keeping her off the field for two months. Two days after she returned in the fall, she was tabbed to hit in a scrimmage — and panicked. Pacing in the dugout. Shaking.

She reached her hand underneath her jersey, pulling the necklace from underneath a turtleneck and clasping it with both hands. Breathing. Like her dad taught her.

“It helps my attitude a lot,” Allen said of wearing her necklace. “Because before, I would be so sad … I would just want to go home, go to my room, and just go to sleep.

“But now,” she continued, “I feel like I have more of a reason to be here.”

The same purpose burns within teammate Rio Mendez, a junior shortstop who wears a gold necklace given to her by grandmother Norma. A month ago, Mendez said, doctors diagnosed Norma with Stage 4 pancreatic cancer, saying she had months to live.

Forty years ago, Mendez said, her grandmother’s brother gave her that same necklace, handcrafted with her name engraved in the shape of home country Puerto Rico. Now, if it’s not around her neck, Mendez feels something is missing.

“Make people remember me,” Mendez, a Utah softball commit, said of the necklace. “Make people look up to me. It really gives me that fire.”

Not all are in favor of the rule change. Grand Terrace coach Robert Flores doesn’t permit his players to wear jewelry, citing the potential risk for injury caused by an earring or lip piercing if a ball takes a bad hop.

But for teams like Gahr that have embraced the freedom, it’s made a noticeable difference.

“It just feels different,” Allen said, “walking onto the field knowing that you have a piece of someone with you.”

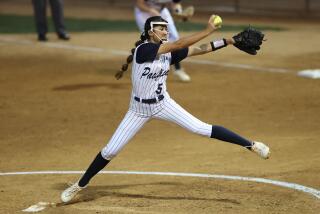

Ridiculous pitching performances

Within the span of two days, two of the best pitching performances were delivered this season.

On Friday night, Orange Lutheran’s Brianne Weiss struck out 20 batters in a 3-0 win over Chula Vista Mater Dei.

The very next day, Burbank freshman Maddison Kellogg whiffed 22 across 12 2/3 innings in a 1-0 loss to Crescenta Valley.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.