Baseball reveres Jackie Robinson, but Robinson didn’t revere baseball. Here’s why

- Share via

Dave Roberts, Reggie Smith and Fred Claire reveal how the Dodger legend has influenced their lives.

- Share via

You have your best day ever on the job and I have mine.

Mine is the day Jackie Robinson came to town.

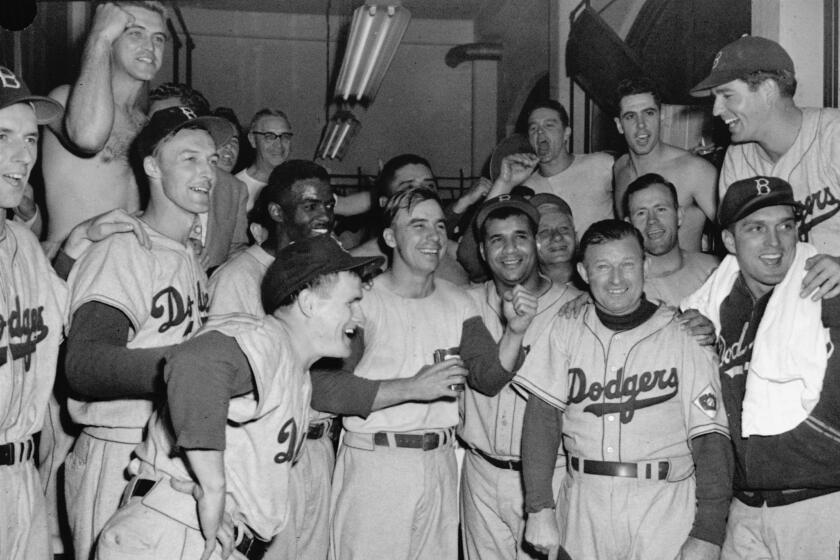

It was June 1972 and I was covering the Dodgers for The Times and Robinson had arrived to have his number retired along with those of Sandy Koufax and Roy Campanella in ceremonies at Dodger Stadium. These were the first numbers the Dodgers had retired, in Brooklyn or Los Angeles, which made it a big deal. So did the fact that Robinson had bothered to come.

While Koufax and Campanella always will be revered Dodgers alumni, Robinson had nothing to do with the team after he left baseball. Following the 1956 season, the Dodgers traded him to the Giants and he abruptly retired. That was the beginning of an estrangement from the Dodgers, and from baseball, that lasted the rest of his life.

He seldom appeared at any of the game’s ceremonial events — a short, gracious acceptance speech at his Hall of Fame induction in 1962 was an exception — and he refused to attend old-timers’ games so often that teams stopped inviting him. And he almost never came to Dodger Stadium.

But Robinson succumbed to the pleas of his friend and former teammate Don Newcombe, who worked in the team’s community relations department, and agreed to come. And here is the strange part. The Dodgers did not bother to call a news conference for Robinson, or for Koufax and Campanella, either. Nor did they mention that 1972 marked the 25th anniversary of Robinson’s major league debut. They seemed to be treating a historic moment as just another Cap Day.

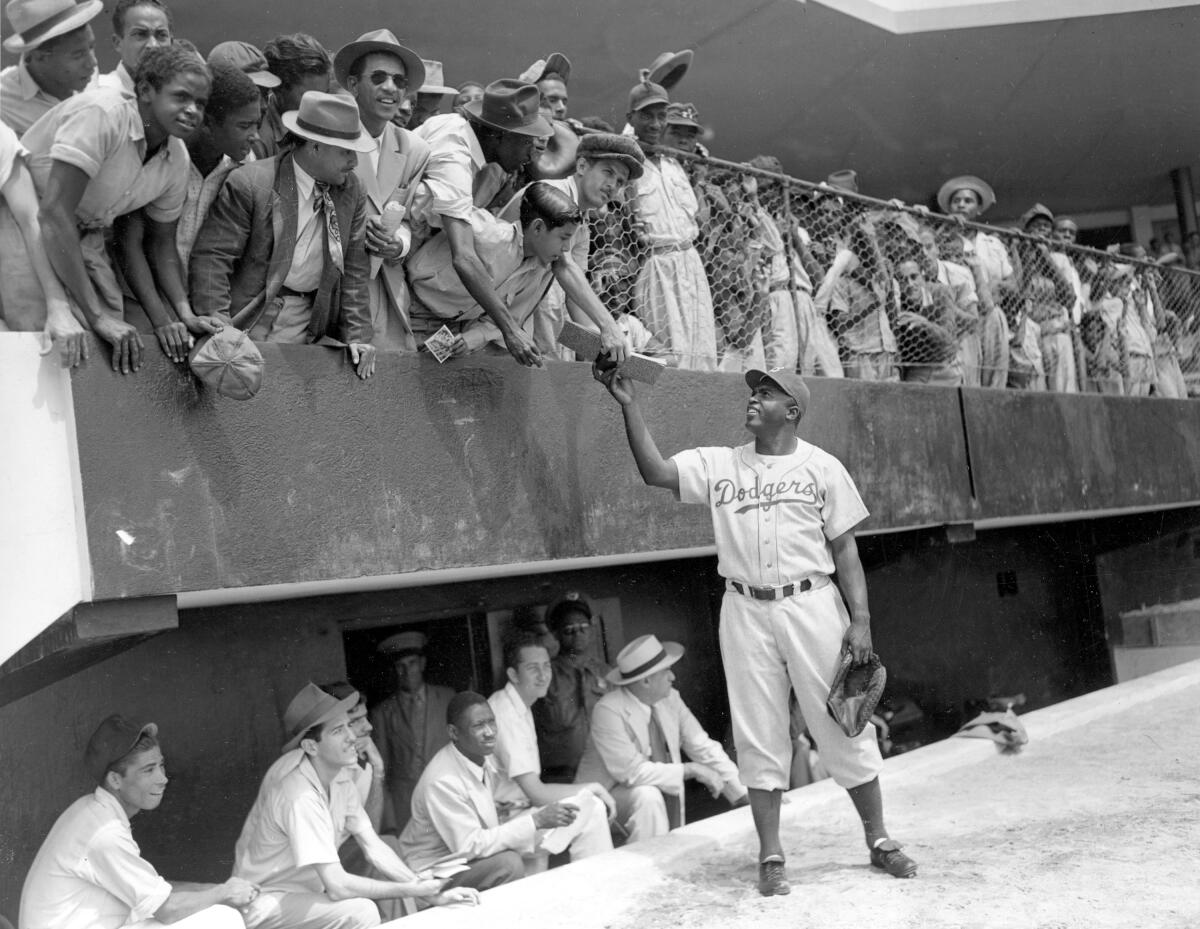

Now, of course, as Major League Baseball celebrates the 75th anniversary of his first game Friday, Jackie Robinson Day is one of the game’s signature events. There are celebrations in ballparks nationwide, with tributes and proclamations hailing the courage and tenacity Robinson displayed in breaking a racial barrier that had existed since organized baseball began. One thing missing from these anniversary events is any mention of how those barriers came to be constructed in the first place.

Seventy-five years ago Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. Fifty years ago he returned to Dodger Stadium, a thaw in a frosty relationship.

No one, of course, expects today’s baseball owners and executives to assume guilt for the actions of those who came before them. But any honest reckoning of Robinson’s legacy, of his triumph over bigotry, must take into account how that bigotry was allowed to persist.

So the feel-good institutionalization of the annual Robinson tributes has led me to a conclusion that might be uncharitable, but here it is. Baseball is lucky that Robinson died at the young age of 53 because to him the self-satisfied celebrations of Jackie Robinson Day would be just another example of white America’s patronizing indifference to the struggle of Black America.

::

I called the Dodgers to ask if they could tell me how to reach Robinson and Newcombe to ask why he thought he had agreed to participate in the number-retirement ceremony. Newcombe said the death two months earlier of Gil Hodges, the Dodgers’ beloved first baseman, two days short of his 48th birthday had played a role in Robinson’s decision.

At Hodges’ funeral, Robinson said that he thought he would be the first of what the author Roger Kahn had called the Boys of Summer to die. Then Newcombe added, “He knows he’s been bitter about a lot of things and he doesn’t want people to remember him that way.”

Robinson regretted his estrangement from baseball and was trying to make amends, Newcombe added. As for getting in touch with Robinson, the Dodgers said he was staying downtown at the Biltmore Hotel. I could call him there.

The thought of talking to Robinson, who had always been a storybook figure to me, stirred emotions I had never experienced as a reporter when interviewing Michael Jordan, say, or Muhammad Ali. My anxiety increased when I called the hotel, told the operator I would like to speak to Robinson and, moments later, found myself doing so. What? Anybody can just call in off the street and talk to Jackie Robinson?

Flustered, I introduced myself and asked if it might be possible to meet with him … whenever he had a few minutes … when he was not too busy.

“Come on over now,” he said.

I had interviewed major sports figures hundreds of times, I told myself as I walked the short distance from the old Times building downtown to the hotel. It was going to be easy. But after knocking on the door and being told to come in, I was thrown off stride again.

The room was completely dark and it took a moment for my eyes to adjust to see how small it was. No suite for Jackie Robinson? Nobody there to attend to him, to see to his comfort?

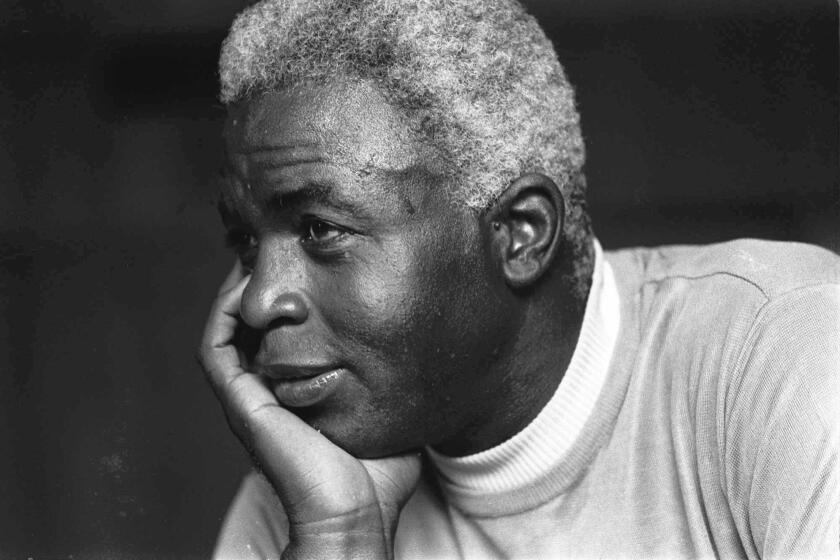

“The light hurts my eyes,” Robinson explained, and he turned on a bedside lamp. What I saw was an old man in his underwear lying under the covers in the middle of the afternoon. He had been sleeping, I realized, and I had woken him up. Dammit!

Robinson’s health was a disaster by then. He had had a heart attack, suffered from diabetes and was almost blind. He could no longer drive a car or play golf — the racetrack was his last refuge — and he had trouble walking without help. Seeing him like this, I was struck with an almost unbearable sadness.

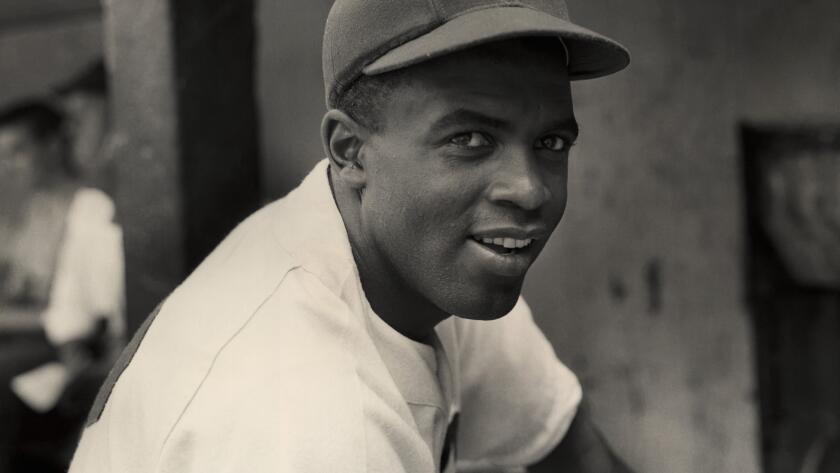

In his prime, Robinson might have been the greatest all-around athlete in the world. He had been a magnificent running back at UCLA — the few grainy clips available on YouTube are amazing — and had won the NCAA long jump championship. He seemed certain to compete in the 1940 Summer Olympics, scheduled for Tokyo, before they were canceled during the military buildup to World War II.

And, Harley Tinkham, a veteran Times sportswriter we called Ace because he knew everything, once told me that Robinson’s best sport was basketball, which he had also played in college.

But now, as I looked at the sick old man in bed, it was hard to remember he was only 53.

As we began to talk, though, it became clear that while Robinson’s body may have betrayed him, neither his mind nor his passions had dimmed.

I leaned into the light coming from the lamp so I could see my notebook and asked an obvious first question: How did he feel about having his number retired? Any expectation of an anodyne answer — it was a great honor, it would be good to see old friends — disappeared in an instant. Was I there to talk about trivial things, his answer indicated, or did I want to know what was on his mind? And he began to talk.

“Baseball and Jackie Robinson haven’t had much to say to each other,” he said, and now that he had come to Los Angeles he had used the occasion to tell Dodgers President Peter O’Malley about what was troubling him: The lack of Black managers in the game. (Frank Robinson would not break that barrier for three more years; Dave Roberts would not do so for the Dodgers for 44 more years.)

“I told Peter I was disturbed at the way baseball treats its Black players after their playing days are through,” he said. “It’s hard to look at a sport which Black athletes have virtually saved and when a managerial job opens they give it to a guy who’s failed in other areas because he’s white.”

Former Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine was teammates with Jackie Robinson from 1948 to 1956. He recalls his relationship with the man who broke baseball’s color barrier.

O’Malley had seemed concerned, Robinson said, and he was grateful for that, but it was not enough. Thinking about this later, I realized that this was an essential truth about understanding Robinson. Nothing would ever be enough. He would never stop fighting injustice where he saw it. He would never allow himself to slip into a satisfied baseball dotage. Even when the game wanted to honor him, he would make it squirm.

As for the retirement of his number, “I couldn’t care less if someone is out there wearing 42,” he said. “It is an honor, but I get more of a thrill knowing there are people in baseball who believe in advancement based on ability. I’m more concerned about what I think about myself than what other people think.”

He spoke of his estrangement from the game, of how, because of his refusal to indulge in the celebrations it offered him, he was viewed in some quarters as an ingrate. He didn’t care.

“I think if you look back at why people think of me the way they do,” he said, “it’s because white America doesn’t like a Black guy who stands up for what he believes. I don’t feel baseball owes me a thing and I don’t owe baseball a thing. I am glad I haven’t had to go to baseball on my knees.”

A reconciliation with the Dodgers was out of the question, he said. The great irony of Robinson’s relationship with the Dodgers is that while he was the embodiment of the team’s brave stand that integrated baseball, which has been called the greatest moment in the game’s history, he was also trapped between the man who had taken that stand on his behalf and the one who replaced him.

Robinson had revered Dodgers owner Branch Rickey, but when Walter O’Malley took control of the team in 1950, O’Malley believed Rickey had cheated him out of $50,000 in the transaction. (“That was a lot of money in those days,” Peter O’Malley told me.)

“Anybody who had anything to do with Mr. Rickey was a bad guy to Walter O’Malley,” Robinson said. “When Mr. Rickey left the club, there were real problems between me and Mr. O’Malley.”

We had talked for an hour and it was time to go, to let him turn off the lamp and sleep. But suddenly I was surprised to hear myself asking a question I had never asked a sports figure before. Had he ever considered his place in history? His answer indicated that he had.

“I honestly believe that baseball did set the stage for many things that are happening today and I’m proud to have played a part in it.” Robinson said. “But I’m not subservient to it.”

My mind was racing as I walked back to the office, went through my notes and began to write. This is good stuff, I thought, using the universal sportswriters’ shorthand for compelling material. A day or two later, the story was played across the top of the Sunday Sports section, and I permitted myself a moment of satisfaction while wondering if Robinson might see it. I would soon find out.

A week or so later, I was going through my mail in the office when I was startled to find a letter from Robinson. It was short and had a few kind words for what I had written, but then got straight to the point. Newcombe had been trying to peddle that crap about him regretting his estrangement from the Dodgers and baseball for years and I was not to believe a word of it. He regretted nothing, he wrote, nothing at all.

::

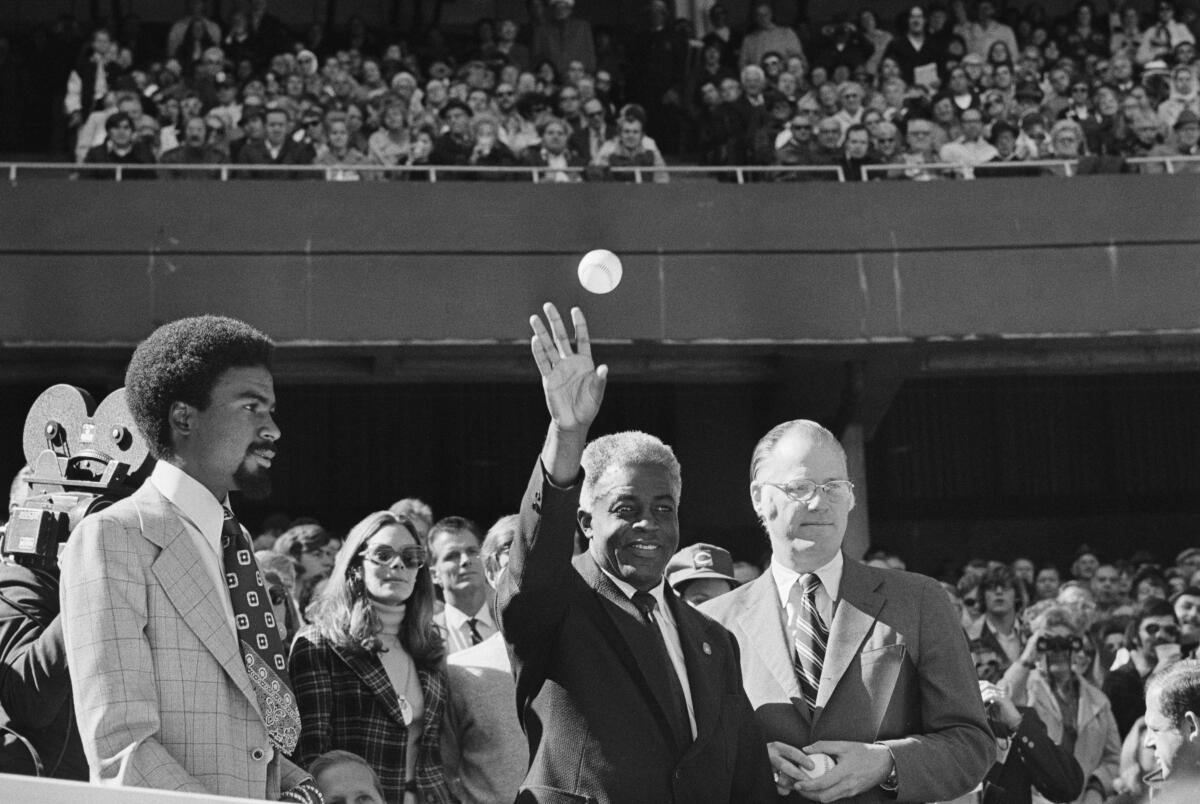

Four months later, on Oct. 15, before the second game of the World Series in Cincinnati, baseball held its only official observance of the 25th anniversary of Robinson’s major-league debut. It was a modest affair with only a few people on the field taking part. Red Barber, who had chronicled Robinson’s career as the Dodgers’ broadcaster, was the master of ceremonies and he introduced Robinson’s family, his former teammates Pee Wee Reese and Joe Black, baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, Peter O’Malley and a few others.

Robinson, looking sharp in a light summer suit, seemed to be honestly touched by the tribute and enjoying himself. And when it was his turn to speak, he offered a few pleasantries about what a thrilling afternoon it was and how he wished Branch Rickey could have been there. And then, just when it appeared he might speak softly for once, he dropped the hammer.

“I’m extremely proud and pleased to be here this afternoon,” he said. “But I must admit I’m going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third-base coaching line one day and see a Black face managing in baseball.”

There was a smile on his face as he made what was to be his final public utterance, one that he had made certain contained one last slap in baseball’s face.

He died nine days later at his home in Stamford, Conn., leaving baseball free to celebrate his life without the inconvenience of having him around to object. To remind the game, and all of us, of the true baseball legacy of Jackie Robinson.

Kostya Kennedy discusses “True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson,” which takes on pivotal years in the life of baseball’s first Black player.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.