Column: Fernando Valenzuela’s lasting impact on baseball makes him worthy of Hall of Fame

- Share via

Talk about a blown save.

Then again, the Dodgers are the same organization whose miscalculations resulted in a seven-year television blackout. Of course they dropped the ball when presented with a perfect opportunity to officially remove Fernando Valenzuela’s No. 34 from their jersey rotation.

But, hey, the 50-year anniversary of Fernandomania is only a decade away. Maybe the Dodgers will come to their senses by then.

Leading up to the celebration Sunday of Valenzuela’s landmark rookie season, there were renewed pleas for the franchise to make an exception to its arbitrary policy of retiring only the numbers of Hall of Famers. The widespread calls spoke to the enormity of Valenzuela’s legacy. They also obscured a more egregious omission.

Valenzuela should be enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

‘Fernandomania @ 40’ is a multi-episode documentary series that examines star pitcher Fernando Valenzuela’s impact on the Dodgers, Major League Baseball and the Latino community in Los Angeles 40 years ago.

Before refuting the premise by citing his career numbers or the brevity of his peak, consider this: Bud Selig, former Major League Baseball commissioner, is a Hall of Famer.

Which isn’t to say Selig isn’t deserving.

If Selig hadn’t supported the home run surge of the late 1990s by looking the other way when players started injecting themselves with steroids, who knows whether baseball would have ever recovered from its last work stoppage?

I’m only half-kidding.

Seriously, if commissioners can receive baseball’s highest honor for creating the stage on which today’s players perform, a player should be able to too.

Outside of Jackie Robinson and maybe Babe Ruth, Valenzuela reshaped baseball’s landscape more than any other player in history. He expanded the game’s customer base. He further internationalized the player pool.

His importance to the Dodgers, in particular, was critical to the point that former owner Walter O’Malley imagined him before he existed. Longtime Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrín has often talked of how O’Malley wanted to find a “Mexican Sandy Koufax” to attract Los Angeles’ growing Mexican and Mexican American populations.

The Dodgers actually found him, which was in itself a miracle. People in U.S. soccer circles have spent decades looking for a Mexican American star and the best they have come up with is, who, Herculez Gomez?

Valenzuela made the Dodgers the team of a community that once viewed the franchise with suspicion. Sheriff’s deputies literally dragged Mexican Americans out of their Chavez Ravine homes to clear the land on which Dodger Stadium was later built.

The audience that was won over by Valenzuela remains.

Years ago, Mexican-born Julio Urías was asked whether his father ever told him stories about Valenzuela.

“My grandfather did,” Urías replied.

In addition to inspiring the multiple generations of Latin American players, Valenzuela created multiple generations of Mexican fans.

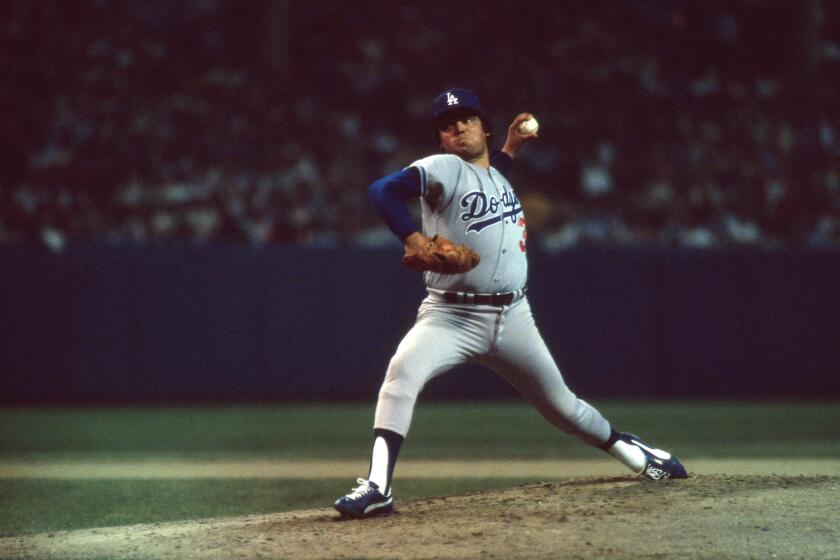

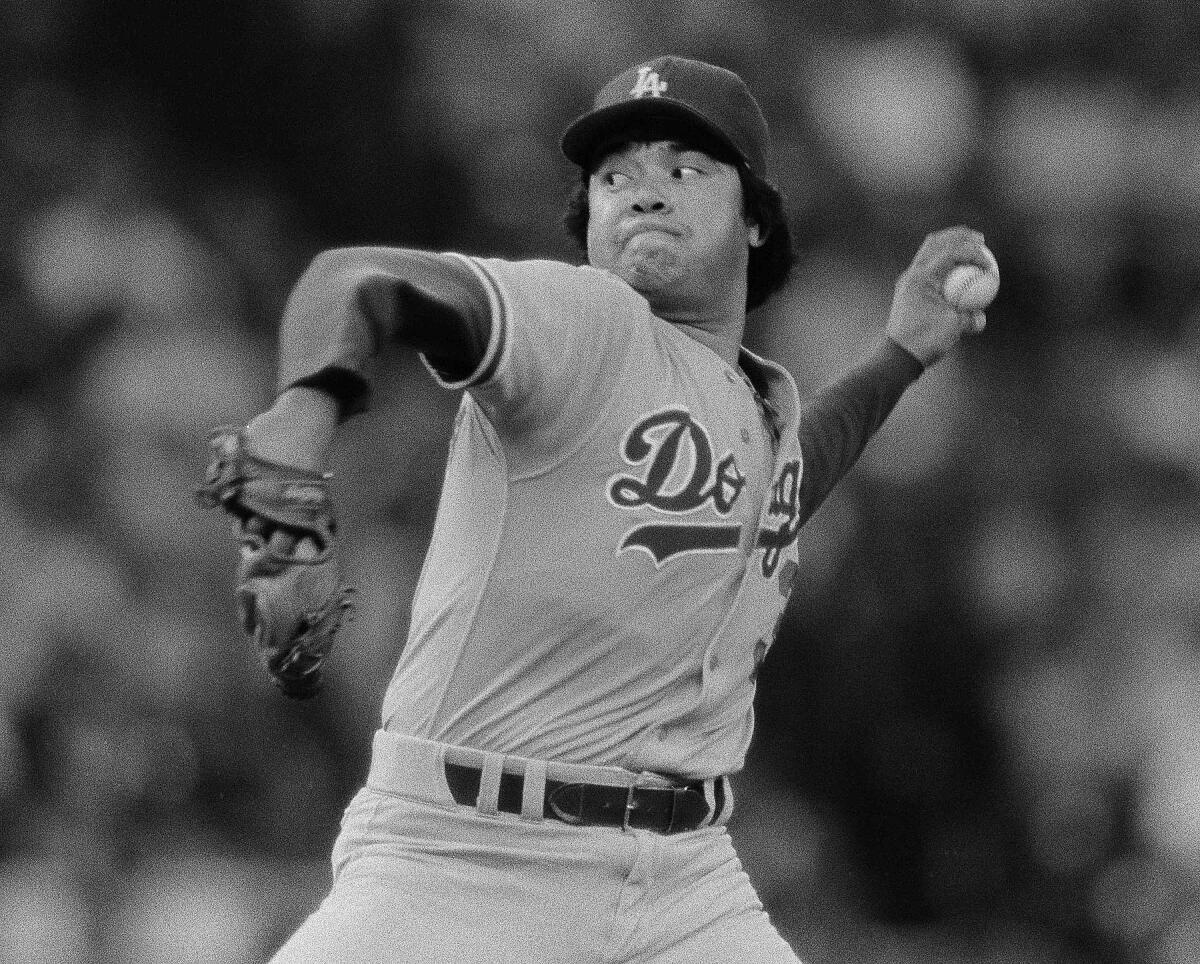

Fernando Valenzuela became a star pitcher with the Dodgers in 1981, igniting Fernandomania and giving Mexican Americans a hero still revered today.

The children of Valenzuela’s fans, and now even their children, have become Dodgers fans. Now, more than 40% of the team’s fans are Latino. Jarrín has often remarked on their loyalty. To his point: The Dodgers have fielded some bad teams over the last 20 seasons and all but one of them finished the season with an annual home attendance of more than 3 million fans.

During a videoconference he participated in with Valenzuela over the weekend, Jarrín spoke of how “El Toro” helped immigrants find their place in this city. Jarrín said his favorite memory of the 1981 season was of the time he accompanied Valenzuela to a luncheon at the White House that was staged in honor of then-Mexican President Jose Lopez Portillo.

“The most powerful people in the government were in line waiting so that a young man from Mexico who didn’t speak English could sign an autograph for them,” Jarrín said.

And Valenzuela could pitch.

Through the 1986 season, he was 99-68 with a 2.94 earned-run average, 84 complete games and 24 shutouts. The workload eventually caught up to him.

Dodgers rookie Zach McKinstry, known as Z-Mac to teammates, hits a two-run home run and doubles in a run in a 3-0 win over the Washington Nationals.

The Dodgers’ Spanish-language voice since 1959, Jarrín is without question worthy of his place in the broadcaster’s wing of the Hall of Fame. But even he acknowledged he was elected in part because of Valenzuela. In addition to calling games, Jarrín served as Valenzuela’s interpreter at news conferences, which gained him exposure in other markets and, by extension, the electorate of the Hall of Fame’s Ford C. Frick Award.

Valenzuela deserves a place alongside him.

Valenzuela could receive the Buck O’Neil Award, which the Hall of Fame presents once every three or more years to “an individual whose extraordinary efforts enhanced baseball’s positive impact on society, broadened the game’s appeal, and whose character, integrity and dignity are comparable to the qualities exhibited by O’Neil.”

Or he could be elected to his rightful place in the Hall of Fame by the Veterans’ Committee, which considers candidates who are no longer eligible to be voted in by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. Valenzuela would have to be chosen by the Today’s Game Committee, which will hold its next election in 2022.

Reflecting on his rookie season, Valenzuela spoke of the importance of the emergency start he made on opening day.

“If things had turned out differently, if I didn’t do my job, we don’t know if there would have been more opportunities, no?” Valenzuela said.

Jarrín agreed, but not completely.

“Nonetheless,” Jarrín said, “logically, the talent would have emerged sooner or later.”

The same applies. Valenzuela’s place in history is secure. Sooner or later, it has to be properly recognized.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.