Commentary: Ali’s legacy from the Parkinson community’s perspective

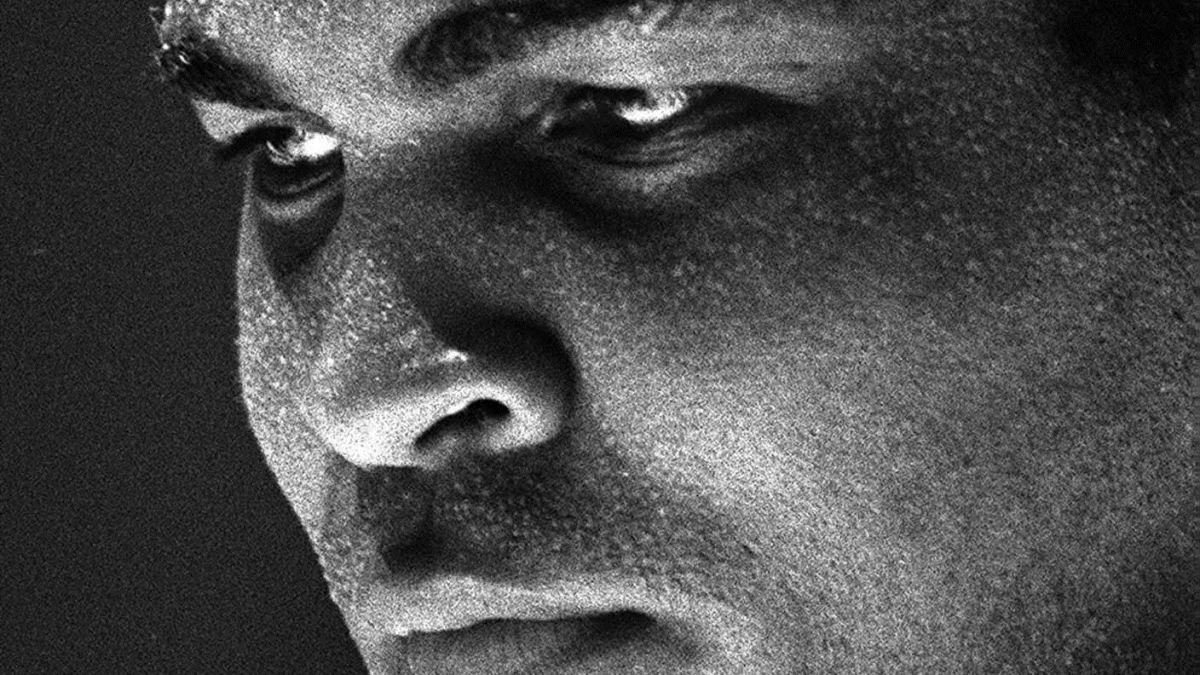

World Heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali after a fight in April 16, 1975 in Miami, Fla.

- Share via

When celebrities develop a disease, many choose to use their power and fame to bring attention and research dollars to their ailment.

The efforts of these “limelight ambassadors” affect thousands of people worldwide, offering hope and a window into the mysterious world of disease progression.

In this respect, Muhammad Ali really was the greatest.

Ali not only used his larger-than-life status to raise awareness about the disease, he also raised hope. He showed the 1 million Parkinson’s disease patients in this country that you can live for decades — good, high-quality decades — with the disease. When he lit the Olympic torch in 1996 in Atlanta, he lit a fire in all of us, particularly in the Parkinson’s community, who saw in him hope for all.

In the weeks since Ali’s death, many of my patients have discussed just how inspiring the world’s greatest fighter has been throughout his final, most protracted battle. Even as the disease stripped him of his poetry and fast fists, he stayed comfortably in the limelight.

It is telling of Ali’s legacy that he remains as important a figure in his death as he was in his life. My patients’ reactions have varied, their thoughts filtered through their own experiences and personalities. But one common theme is that Ali represents the fact that the disease doesn’t have to define you.

The website for the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center in Phoenix reads: “A diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease or another movement disorder is not a death sentence. Recent advances in medicines and surgical treatments have given you new weapons to fight against your disease.”

This was the essence of what Ali was about. The fight.

Today, advances in diagnosis and treatment has, indeed, accelerated our understanding of the disease. I work with patients all the time who are able to combat tremors, swallowing issues and other of the more troubling aspects of the disease better than ever before.

He was the embodiment of how important it is to stay active. At Hoag, for instance, many of our patients participate in therapeutics such as boxing classes, PWR, and Forced Use therapies, which teaches Parkinson’s patients to slow down the progression of the disease.

He also stood as a reminder that Parkinson’s is not necessarily something you get late in life. Ali was in his 40s when he was diagnosed, and I use his story to remind people that if you notice tremors, stiffness, slowing down or loss of balance, see a specialist. Early.

Ali kept a medical team close: internists, neurologists, and Parkinson’s specialists. In this way, he also exemplified the importance of engaging neurologists trained to deal with movement disorders.

Before beginning my neurology fellowship at UCLA, I considered the fellowship program at Ali’s center. When I visited, I was in awe of the man — how successful his career had been, how deep his soul was and how dedicated he was to helping others.

As commentators from the world of boxing to the world of civil rights have eulogized the legend, I — and my patients — remain inspired by the man. For us, Ali represents the fight against Parkinson’s disease. A fight he took on with dignity and pride and a commitment to us all.

--

SANDEEP THAKKAR, D.O., is a movement disorders specialist at the Hoag Neurosciences Institute Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Program.