Commentary: Atomic veteran’s experience with 31-kiloton nuke is worth recalling as ‘Doomsday Clock’ resets

- Share via

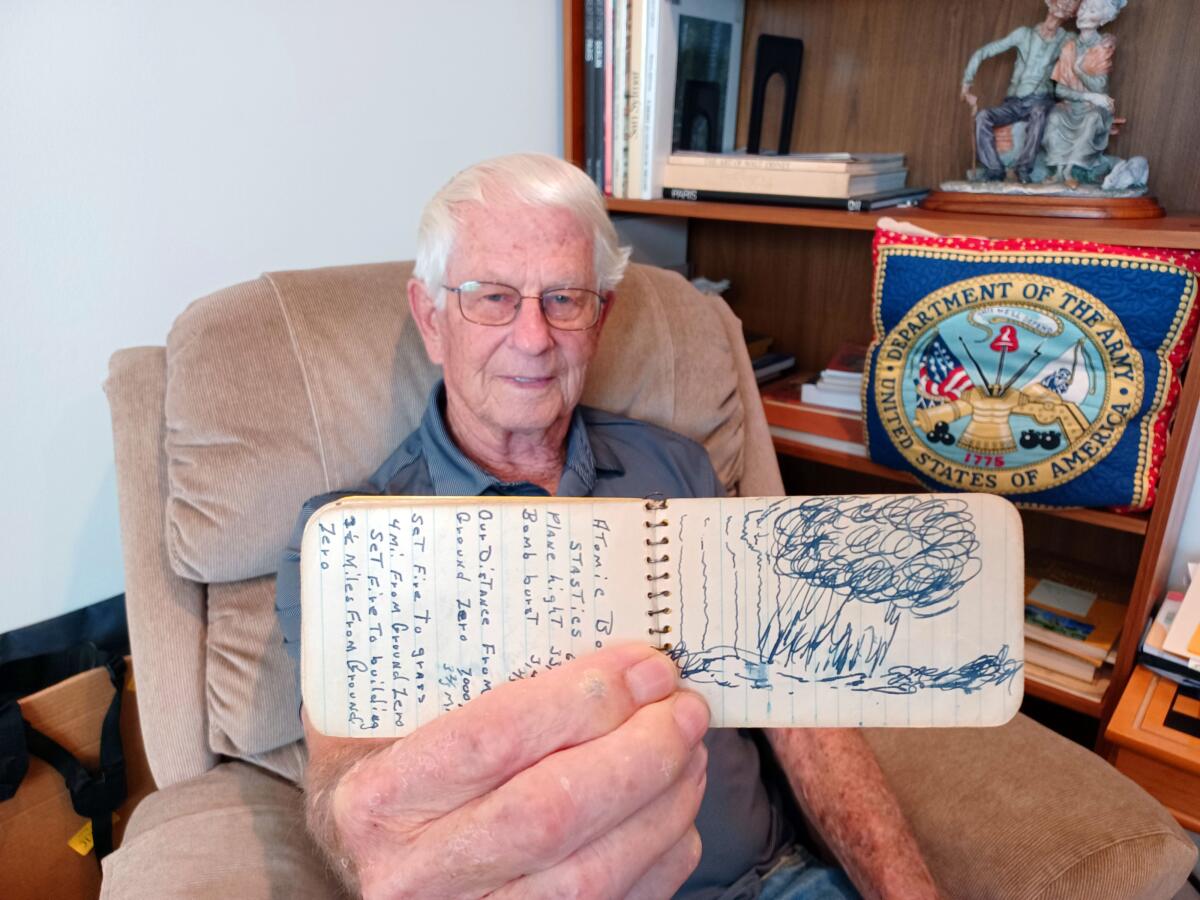

Ray Calloway is active, articulate and mostly free from the chronic health conditions that can dog aging citizens.

Most weeks, the 92-year-old travels from his home near Golden West College to the Huntington Beach Tree Society’s Urban Forest off Ellis Avenue, where he spreads mulch and waters the younger plants.

Ray likes the fresh air that blows off the Pacific and is mostly free of contaminants.

He can recall other days when the air was dirtier — like April 22, 1952, for instance.

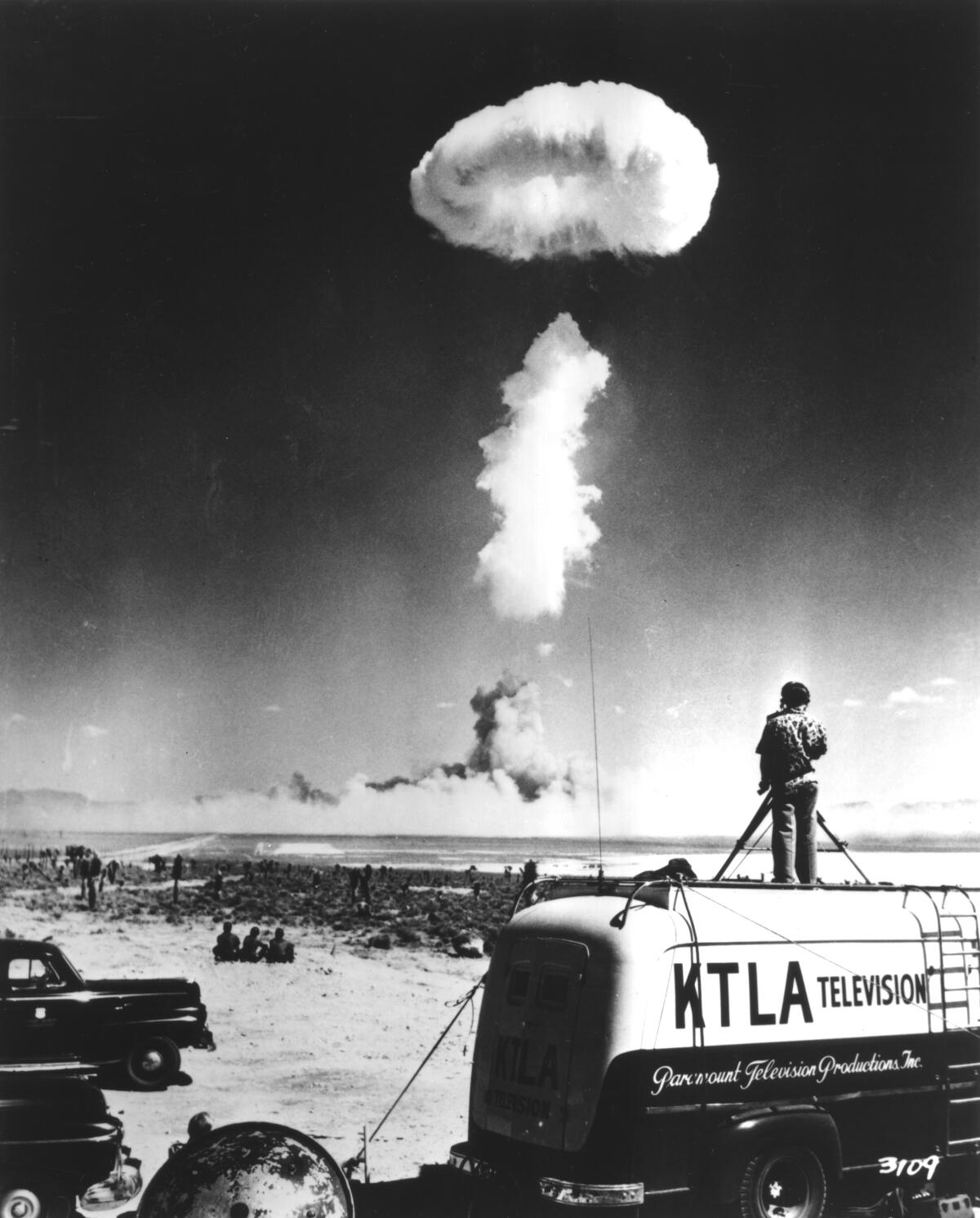

On that morning, Ray crouched in a foxhole at the Nevada Test Site as a B-50 (a souped-up B-29 bomber) passed overhead. A little after 9:30 a.m., the aircraft dropped a device that fell to a point 4,000 feet over the desert about 3 and two-thirds miles from where Ray crouched. There it detonated — releasing 31 kilotons of explosive energy.

Dubbed Charlie, the device unleashed double the yield released by the bomb that leveled Hiroshima.

Ray turns eloquent when he recalls the blast and its aftermath. It’s obvious that the experience remains vivid.

“The most beautiful crimson I’ve ever seen,” he recalls of the mushroom cloud. “Shaped like a doughnut, with white clouds coming out of the center, rolling over the outside and back up through the center. Just like it was boiling up there in the sky.”

What most surprised him was the eerie silence that followed the initial flash.

“How come no sound?,” he recalls thinking. “I was just amazed that I didn’t feel and sense an enormous blast wave.”

In our chat, Ray quickly reviews the physics. With the speed of sound around 700 miles an hour, it took about 13 or 14 seconds for the blast wave to reach the men.

By that time, most, including Ray, had emerged from their foxholes and were staring at the spectacle.

“I experienced a lot of dirt and dust in my face as a result,” he recalls.

In the film “Oppenheimer,” the blast wave takes more than a minute to engulf the famous scientist. That’s a bit of artistic license. (Observers were about 6 miles from the Trinity test and would have felt the blast wave after roughly 30 seconds.)

As with the film, Calloway’s story provokes thought. What would it be like to experience such a blast in person?

His tale brings to life the immense power of nuclear explosions. And the weapon he witnessed is relatively small compared to today’s — many use atomic explosions to spark secondary fusion reactions. Their power ranges into the hundreds of kilotons.

If Ray’s bomb went off at the Huntington Beach Pier, the house I grew up in at Beach Boulevard and Atlanta Avenue would immediately ignite — then be swept away by the blast wave several seconds later. That thought gives me pause when I think of it.

Reliable defense against a determined nuclear attack does not exist, most experts agree.

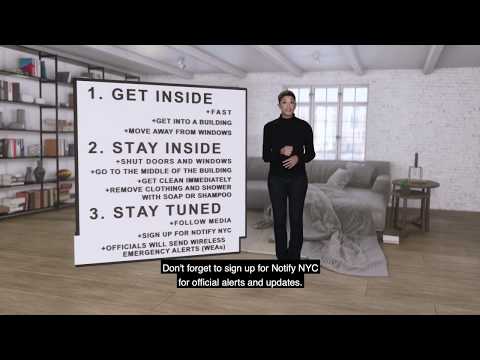

A 2022 New York City civil defense video famously told residents “You’ve got this” after sharing tips for surviving thermonuclear war. It was widely ridiculed.

“Civil defense campaigns [like this] undermine public trust,” responded Jeffrey Lewis of the East Asia Nonproliferation Project at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey.

“The advice … is so obviously inadequate,” Lewis added. “You definitely do not ‘got this.’”

In 1980, during the height of the Cold War, Huntington Beach civil defense and emergency services director George Thyden advised yacht-owners to stock food and water — and head for the far side of Catalina Island if war loomed.

There “they would be protected against the blast, thermal threat and fallout,” Thyden told the L.A. Times in 1980.

Thyden’s advice for non-boat-owners? Ask a boat owner to invite you aboard.

After an hour with Calloway, a bigger picture emerged of Operation Tumbler-Snapper and Desert Rock IV — code names for the nuclear test series and troop maneuvers he took part in.

The series (and several that followed) were comprehensive dress rehearsals for using tactical nuclear weapons in battle.

Ray and other soldiers were monitored during the tests (and interviewed afterward) to detect any fear or reluctance to participate. Did he detect any fear or reluctance?

“I did not,” he recalls.

With the current state of the world, and its ongoing conflicts, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on Jan. 23 confirmed its famous Doomsday Clock scale at 90 seconds to midnight — the most urgent setting since it debuted in 1947.

“China, Russia and the United States are all spending huge sums to expand or modernize their nuclear arsenals, adding to the ever-present danger of nuclear war through mistake or miscalculation,” the Chicago-based organization’s statement read.

Calloway thinks full-scale simulations of nuclear war like the one he took part in can only encourage leaders to pull the trigger.

“As unfortunate as it may seem, [tests like mine] make it more likely that [these weapons] will be used.

“That was the purpose of our exercise — to prove to the world that the U.S. has people trained in the use of tactical nuclear weapons. That they have experience and know how to use [nukes] on the battlefield.”

Decades without atmospheric testing and reported close calls have likely lulled the public into thinking nukes aren’t much of a threat today, journalist Abe Streep mused in the publication Scientific American last year.

“We’ve forgotten how to think about [nuclear weapons],” Streep wrote in his story about the U.S. government’s plan to spend $1.5 trillion on a new generation of modernized nukes.

Among Calloway’s memories is marching toward ground zero an hour after the explosion. Along the way soldiers passed cages where sheep had endured broiling before they succumbed to the blast.

Calloway knows he is lucky. He’s one of the 235,000 atomic veterans exposed to radiation during the atmospheric testing era that did not develop cancer. An unknown number of thousands did.

At the end of our conversation, Calloway expressed gratitude for the aircraft crew that placed the bomb at its target. If they had been off by a mile or two, the outcome would have been very different for him.

“We would have been wiped out,” he said with a chuckle.

Erik Skindrud grew up in Huntington Beach. He lives in Long Beach. Follow him at @Erik_Bookman. The interview with Calloway can be viewed at YouTube here.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.