First and largest Vietnamese-language daily newspaper in U.S. to celebrate 40 years

- Share via

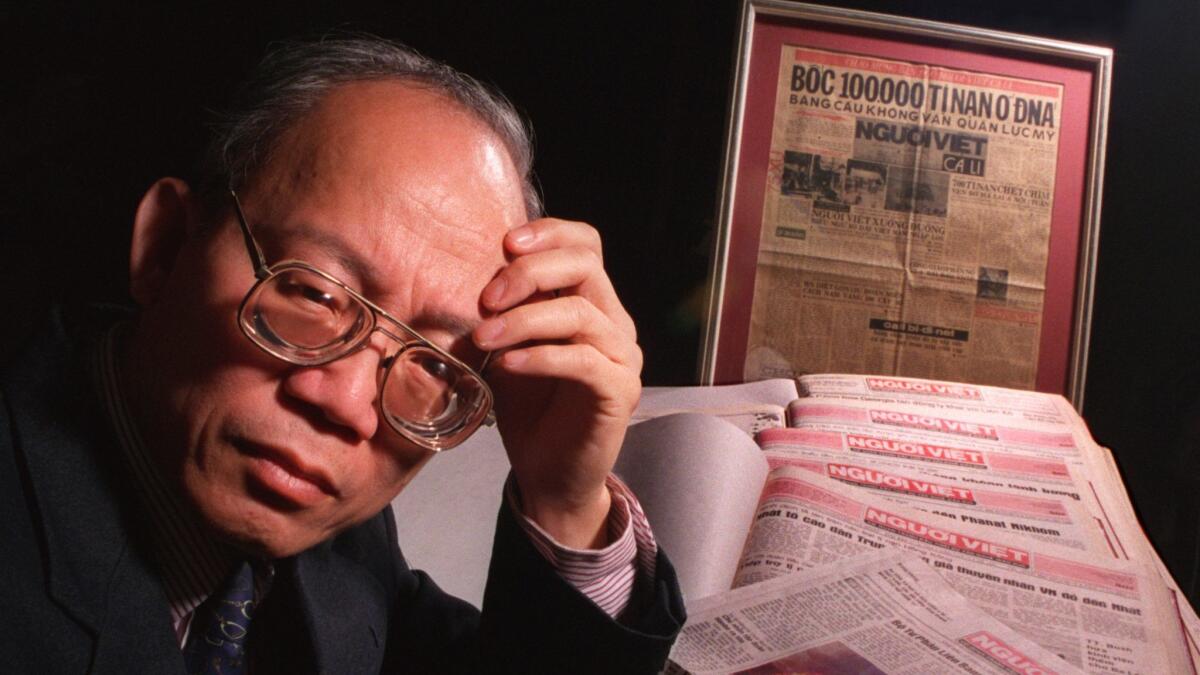

Inside the modest lobby of the Nguoi Viet Daily News hangs four framed newspaper clippings. The headlines tell of a war’s toll.

“100,000 refugees in southeast Asia picked up by U.S. Air Force,” one headline reads in Vietnamese.

“700 refugees drown in the sea off the coast of Malaysia,” another says.

The pages were printed in 1978 in the wake of the decadeslong Vietnam War. Together they form what was the first Vietnamese-language daily newspaper ever printed in the U.S.

Today, the Nguoi Viet Daily News, based in Little Saigon in Westminster, is the largest Vietnamese-language newspaper in the country. The paper will celebrate its 40th anniversary in December.

Yen Do, a war-hardened newsman from Vietnam, started the newspaper a few years after he immigrated to the U.S. in 1975. He knew there was a need for a Vietnamese-language paper in his new home country for the mass of immigrants flooding in.

He published the first paper with the money he made as a house painter. Hung Nguyen, human resources manager at Nguoi Viet — which means “Vietnamese People” — said the first issue was made to look similar to a Vietnamese newspaper, with a red banner at the top of the front page, to sate the nostalgia of the homesick immigrants.

In the early days, the paper was basically a one-man show. Do was the writer, editor, ad salesman and typesetter. He worked out of his garage.

He did get some help bundling papers from his young daughter, Anh Do, who is now a reporter for the Los Angeles Times and serves on the board of the Nguoi Viet Daily News.

“My father was passionate about the paper because he believed you could unite people through the written word,” she said.

He took responsibility for keeping the Vietnamese community informed, including apprising them of the affairs of their former home and preparing them for life in the new one.

The paper would have information about what the price of a kilo of rice in Vietnam is so that people could know how much money to wire home for those left behind.

Other articles detailed how to open a savings account, apply for a home loan and rent an apartment.

“It was a recipe for a new life,” Anh Do said. “Through his stories you would get the ingredients you needed.”

Do didn’t take a cut of the profits for many years, because it was never in his nature to place his well-being over others. He favored community above all else.

“He was as much an advocate as he was an editor,” said Jeff Brody, a professor of communications at Cal State Fullerton who wrote an oral history on Do.

Vietnamese immigrants who came to Do for help would always receive assistance, including money from his own pocket.

In the early 1980s, Do organized a panel of Vietnamese and American doctors to quell the community’s fears when a few Vietnamese children tested positive for tuberculosis in Orange County. The fear was unwarranted because it was normal for Vietnamese children to be vaccinated against tuberculosis to prevent the disease. The practice wasn’t prevalent in the U.S. at the time.

Do regularly would organize community events like this.

Do’s community-first ethos also extended to his staff. The paper subsidized lunches for staffers for $20 a month and they ate together every day.

That practice is still continued today, though for $25.

Do was also fueled by his passion for a free press, something he didn’t have in Vietnam. He went so far as to fund competing newspapers and magazines.

Reporting in Little Saigon wasn’t easy. Anti-Communists have butted heads with the paper throughout its lifespan.

Between 1981 and 1990, five Vietnamese American journalists were killed, including in Orange County. The climate was dangerous for reporters who could be perceived as communist sympathizers if they reported on the Vietnamese government with anything other than deep distaste.

Do regularly received death threats, protesters stormed his office and one of the Nguoi Viet Daily News’ trucks was firebombed in the 1980s.

But Do never let it affect the paper’s output.

“He stayed true to his convictions and published the truth as it is,” Anh Do said.

Do died in 2006 at age 65.

“I would call Yen Do Little Saigon’s leading intellectual,” Brody said. “The scope of his acumen and charity and compassion was unsurpassed. He led a hard life as an editor and publisher, which led to an early death. He should be looked upon as the founder of Vietnamese-language media in the United States and certainly its premier editor.”

Today, the newspaper has continued in the same spirit imparted by Do. The team of five reporters covers local news in Little Saigon, as well as Vietnamese communities throughout the country and abroad. The total staff is about 50, including advertising.

Stories include subjects that go unnoticed by the mainstream press, like Vietnamese farmers and fishermen in New Orleans and Florida.

“We cover things that are very intimate and dear to the community,” Nguyen said. “But these things probably aren’t relevant enough for the big papers.”

Much of the old problems remain the same. Staff still has to negotiate the anti-communist minefield. In 2008, hundreds of them protested outside the Nguoi Viet offices because of a photo that was perceived to be sympathetic to communism.

But the reporters and editors continue on just like Do did.

“We will always report what is going on in Vietnam — good or bad,” said Nguoi Viet editor in chief Nhan Dung Ngo. “Many in the community think we should only report the bad.”

Some problems are new — like how to get people to read.

The print circulation is about 10,000, down from roughly 18,000 in the last decade. But much like other papers, Nguoi Viet is transitioning to being more online-focused.

“You can’t stop change,” Anh Do said. “I can only think it will make us better. We will grow with it.”

Ngo, who used to write for Nguoi Viet during its infancy, remembers the early days were plagued with uncertainty about the future of the paper.

He began writing for it from the frigid terrains of Canada after leaving Vietnam in 1975 on the same U.S. Air Force plane as Do.

Like Do, Ngo wrote for free until the fledgling newspaper could find its way.

”We didn’t think we could survive,” Ngo said. “But here we are.”

Twitter:@benbrazilpilot

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.