A. Alfred Taubman, mall magnate jailed in auction scandal, dies at 91

- Share via

Shopping mall magnate A. Alfred Taubman, who developed the Beverly Center and was a past owner of the Irvine Co. — and who went to prison late in his career for his role in a scandal that rocked the art auction world — died Friday at his home in Bloomfield Hills, Mich. He was 91.

The cause was a heart attack, his son Robert Taubman said in a statement.

Taubman Centers, the company A. Alfred Taubman founded, is one of the top mall owners and operators in the country, specializing in higher-end locales. Its current Southern California properties are the Beverly Center in Los Angeles and the Gardens on El Paseo and El Paseo Village in Palm Desert.

Taubman, who was personally worth about $3 billion, according to Forbes magazine, is also credited with helping develop the suburban mall concept as a place with plenty of parking that offered a “one-stop comparison shopping opportunity,” as he put it in his 2007 autobiography, “Threshold Resistance: The Extraordinary Career of a Luxury Retailing Pioneer.”

He also had several side businesses, including one that got him into trouble. Taubman spent nearly a year in prison and paid about $7.5 million after a 2001 price-fixing conviction while he was chairman of Sotheby’s auction house. Afterward, he concentrated on philanthropic work — his foundation gave hundreds of millions to medical, arts and public policy institutions.

Robert Taubman took over his father’s company as chief executive. But A. Alfred Taubman did not separate himself completely from retail. He attended the company’s mall openings and kept a blog that extolled the values of brick-and-mortar shopping.

In March he wrote about the then-craze concerning a picture of a dress online that appeared to be different colors to different people.

“The technical limitations of computer screens make it impossible to effectively communicate such important product characteristics as fit, color and feel,” he wrote. “There are no fitting rooms or tailors in cyberspace.”

He was born Adolph Alfred Taubman on Jan. 31, 1924, in Pontiac, Mich., to German-Jewish immigrants. By the time he was 11, he was a sales clerk at a department store.

Taubman graduated from Pontiac High School and enrolled at the University of Michigan. But soon after, with the country at war, he enlisted in the military. He spent much of his time in the Pacific theater as an aerial photographer, taking pictures of areas — including Hiroshima — after they had been bombed.

When the war ended, he went back to the University of Michigan but dropped out and joined an architecture firm, where he had a chance to put into practice his theories on easing shoppers’ psychological “threshold resistance” to entering stores. Starting his own firm in 1950, he applied his notions to whole shopping centers, where, for one thing, he put parking out front with easy access to doors.

With his firm thriving, Taubman looked for new ventures. In 1976 he viewed from a helicopter the vast land holdings of the Irvine Co. “I wanted to be involved,” he recalled during a 1987 court proceeding. “It looked like fun.” He put together an investment group that bought the company in 1977 for $337.4 million — or $6,000 a share — and he became company chairman.

In 1983 he sold his shares to Donald Bren for about $200,000 a share.

That same year, he bought Sotheby’s, one of the most prestigious auction houses. But a federal investigation showed that while he was chairman of the firm, it colluded with rival Christie’s to raise the commissions paid by sellers, costing them hundreds of millions of dollars. Taubman’s own schedule books, which prosecutors said showed coded notes from meetings with Christie’s executives, helped convict him at a high-profile 2001 trial. He spent about nine months at a low-security prison in Minnesota.

In his memoir he protested his innocence and said the conviction hurt his name. But it did little to disturb his lifestyle. He still had his home in Michigan, not to mention those in New York, London and other spots. And he drew some sympathy for being the only person sent to prison for the scandal.

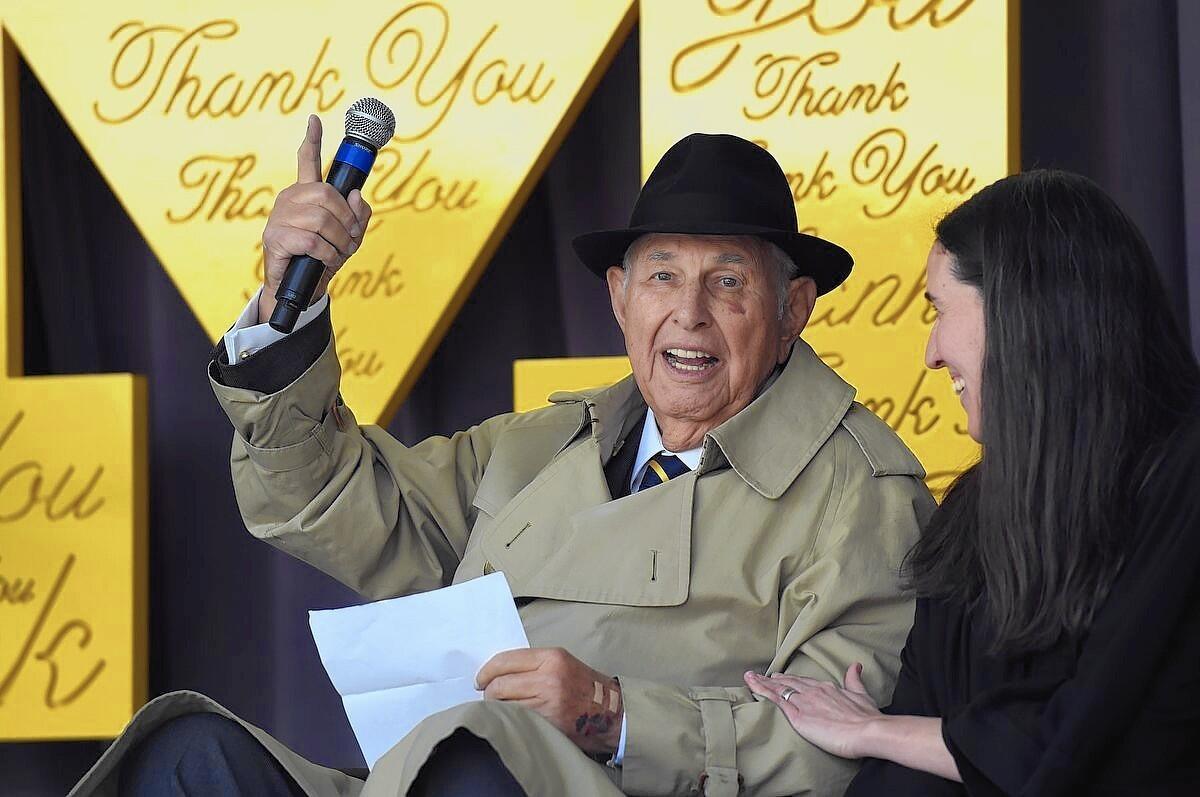

Taubman was eventually able to joke about it. At his 90th-birthday party, he told a crowd gathered for the event that he’d been fortunate to spend all his birthdays with family and friends, except for during the war, “and the year I took off to study the criminal justice system in Rochester, Minnesota.”

In addition to his son Robert, Taubman is survived by his wife, Judith; daughter Gayle Kalisman; son William; stepdaughter Tiffany Dubin; stepson Christopher Rounick; nine grandchildren; and one great-grandchild.

Twitter @davidcolker