New law closes campaign finance loophole exploited by convicted ex-Anaheim mayor

- Share via

California politicians convicted of a crime will no longer be able to use campaign funds to cover legal expenses.

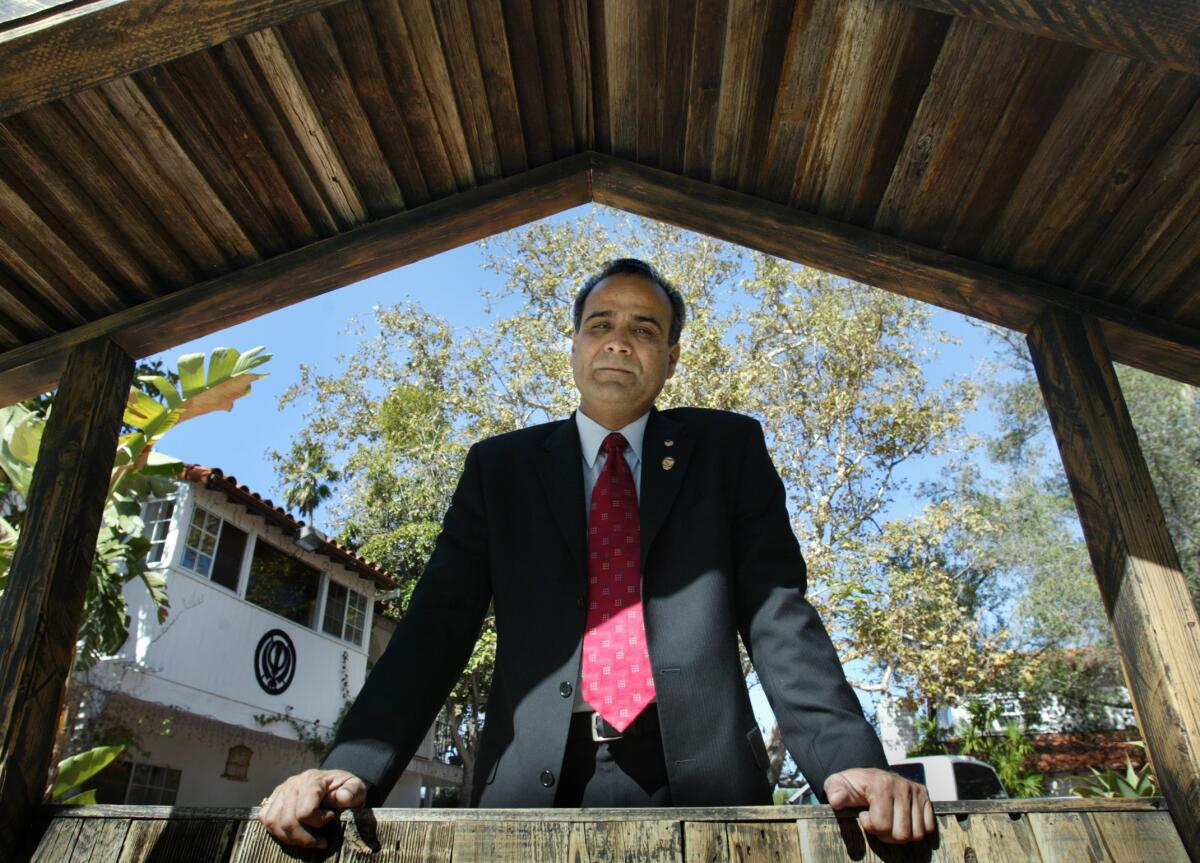

On Sept. 25, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 2803 into law, which closes a campaign finance loophole that former Anaheim Mayor Harry Sidhu used last year to pay his criminal defense attorney amid an FBI political corruption probe.

According to campaign finance documents, Sidhu made a $300,000 payment to attorney Paul Meyer in 2022 from funds raised for his reelection.

Before that, he resigned as mayor a week after an FBI affidavit accused him of bribery, fraud, obstruction of justice and witness tampering.

Assemblyman Avelino Valencia (D-Anaheim), who had publicly called on Sidhu to step down when he served on Anaheim City Council alongside him, introduced the bill in February.

“What Sidhu did was unacceptable and unethical considering the crimes that he was being charged with,” Valencia said. “I don’t think supporters of candidates intended for their money to go towards defending politicians against criminal charges.”

Artin Berjikly spoke before the Sept. 24 Anaheim City Council meeting and pledged to fulfill the duties of his position, which was created in the aftermath of political corruption scandals.

Sidhu eventually pleaded guilty to four felonies, including charges connected to the attempted sale of Angel Stadium, at the Ronald Reagan Federal Courthouse in Santa Ana last September.

“Yes, I’m guilty,” Sidhu said when he entered his plea. “I did lie to the FBI.”

But the former Anaheim mayor is not the sole politician in the state to have exploited the campaign finance loophole.

Former state Sen. Leland Yee paid his legal team $128,000 from campaign committee funds for his secretary of state bid before pleading guilty to racketeering in 2015.

Sean McMorris, ethics program manager for Common Cause, noted the new law as one that is narrowly tailored but important in strengthening the Political Reform Act that was first enacted 50 years ago.

“There are bad actors,” he said. “If you do want to deter them and make ethics laws more important, one way to do that is not allow them to use campaign funds to pay off legal fees or penalties. This is good in that it’s expanding that for felonies as well as bribery.”

Under the new law, if politicians are convicted of a felony among other select crimes, they will be required to pay back donors for any funds diverted to legal expenses.

The law doesn’t cover legal defense funds, which politicians are legally allowed to open and raise money for without contribution limits.

Former state Sen. Ron Calderon and former state Sen. Roderick Wright raised funds through such committees.

“That’s still a loophole,” McMorris said.

The bill, which was co-sponsored by state Sen. Tom Umberg (D-Santa Ana) and Assemblyman Phil Chen (R-Yorba Linda), marks another anti-corruption effort for Valencia, who chairs an Assembly accountability and oversight subcommittee.

He previously ordered a state audit of contracts between Visit Anaheim and the Anaheim Chamber of Commerce after an independent corruption report alleged the two organizations engaged in a grafting scheme involving $1.5 million in COVID-19 relief funds.

An Angels consultant planned a rehearsal for City Hall leaders before a council meeting to approve the sale of Angel Stadium, court records show.

Newsom also last month signed into law AB 2946, a Valencia-backed bill that requires a majority vote by the Orange County Board of Supervisors before discretionary funds can be awarded.

The legislation comes in the wake of a political corruption scandal involving $13 million in public funds directed by Supervisor Andrew Do to Viet Society America, which a county lawsuit now alleges was embezzled by the nonprofit that also employed Do’s daughter.

In closing the loophole exploited by Sidhu, Valencia hopes to protect the intent behind campaign contributions.

“It’s another step in ensuring good government, transparency and ethics in public service,” he said of the new law. “It doesn’t solve some of the gaps still kept in the system, but it’s a step closer for sure.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.