What it’s like to catch the coronavirus for the sake of science

- Share via

On a cold, damp Monday just over a year into the pandemic, Jacob Hopkins tilted his head back in a London hospital and did something no other human had ever done before: He allowed five doctors in full hazmat garb to dribble into his nostrils a precisely calibrated suspension of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Hopkins would go on to become one of the more than 546 million people across the globe to be infected with the virus known to scientists as SARS-CoV-2.

He did it for science.

Hopkins was the first of 36 healthy young Britons to participate in a “human challenge” study of the most consequential virus on the planet. The experiment was widely accepted in the United Kingdom as an efficient way to gain insights into how, where and for how long the virus establishes itself in people.

Knowing the minute details of a coronavirus infection is critical to vaccine and drug designers, to public health officials, and to those caring for patients. Many of those details remained elusive until the study’s findings were published this spring.

Hopkins had only a fuzzy sense of how his act might help others. As a teenager, he had responded to a cousin’s leukemia by signing up with a stem cell registry, and ended up donating bone marrow. This time, he hoped his participation might speed the development or testing of vaccines for low-income countries.

“I would have been devastated if I couldn’t take part,” he said.

In the United States, deliberately infecting humans with the coronavirus was so controversial that American officials declared it a last resort. They argued that scientists could find ways to unlock the virus’ secrets without exposing volunteers to even a tiny risk of death.

Human challenge studies were “Plan D,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who contemplated them only as a way to put a new vaccine through its paces.

Experiments that intentionally expose healthy volunteers to serious harm pose deep quandaries. That’s especially true when too little is known about a virus to predict its impact, and when effective treatments aren’t available.

But in the next pandemic, or even later in this one, some U.S. scientists say they may rethink their resistance.

“We can learn things more quickly by doing challenge studies,” said Dr. Stanley Plotkin, a University of Pennsylvania vaccinologist who was a leading voice in calling for such research.

When an infectious disease is spreading out of control, saving time may be worth the risk, said Arthur L. Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University.

“If volunteers were willing to be infected, you could prevent potentially millions of deaths,” he said.

::

Jacob Hopkins’ path to becoming a human guinea pig wasn’t particularly fraught. He had always been fit, he said, and volunteering “felt like something I could do.”

Hopkins was a 22-year-old history student at Newcastle University when Britain imposed the first of several strict lockdowns. He went home to live with his parents in Birmingham after his school closed.

In the final months of 2020, Hopkins was working in a grocery store and scrolling through his social media feed when he saw an ad with pictures showing attractive people masked and socially distanced, but otherwise equipped with the usual accoutrements of young adulthood — backpacks, schoolbooks and earbuds.

“Help us fight COVID-19,” said the advertisement. Stripped across the bottom, in fine print, was a disclaimer: “You may suffer COVID-19 symptoms if you take part.”

Scientists searching for a medicine to treat patients with COVID-19 are looking for it in the blood of people who have already survived the disease.

It seemed like a way to help the world get back to normal faster. Hopkins’ first love, backpacking abroad, was not an option. Nor was socializing at home. His studies in Cold War history had been put on hold. But the prospect of playing some small role in this historical moment gave him a sense of mission.

In fact, hands shot up across the world. Hopkins was one of nearly 37,000 people who expressed initial interest in participating in the study. Researchers screened 6,135 by phone, winnowing the unresponsive, the unsure and those who were too old or too sick. With 187 potential candidates left, they pruned people who’d become infected, lost interest or had gained access to vaccine. Thirty-six, including Hopkins, were deemed healthy, stable, ready to go.

His parents were “definitely not happy,” Hopkins said. But he was determined to see it through. While his countrymen were letting down their guard after a third round of lockdowns, Hopkins double- and triple-masked when in public. If he got infected before the study began, he’d be disqualified.

“I never wanted to get COVID,” Hopkins said, and then quickly corrected himself. “Well, I did want COVID, but I wanted it at the right time.”

::

In the U.S., scientists at the National Institutes of Health took a step toward launching a human challenge trial early in the pandemic. The government ordered up SARS-CoV-2 viral samples that could be used to deliver precise, genetically identical doses to human subjects.

But that, Fauci told CNN at the time, was an “absolutely far-out contingency.”

He stands by that decision nearly two years later. Even if researchers had an urgent need to test a new vaccine, they could do so without infecting volunteers because the coronavirus is readily available in the world at large, he said in an interview.

Plotkin was among the scientists who lobbied the NIH to conduct a human challenge trial. He said officials were concerned that a volunteer would be harmed “and that if that happened, the reputation of the NIH would be harmed.”

The British, by contrast, “were interested right from the beginning,” he said.

The United Kingdom was uniquely positioned to move ahead quickly with a human challenge study. The National Health Service provides care for all Britons, so participants’ medical and mental health histories are readily available. Its universal healthcare system also means that research subjects would never be refused follow-up care if something went awry. (Neither is the case in the U.S.)

British researchers had a long tradition of studying infectious diseases — including influenza, common cold viruses and malaria — using “controlled human infection models.” The practice came of age in 1946, when Britain repurposed a wartime hospital in Salisbury as a Common Cold Research Unit.

Compensation was the principal inducement for participation, and it remained that way for decades. Healthy people with time on their hands could spend a couple of weeks in what was sometimes billed as “Flu Camp.” They’d depart well-fed and rested, with some cash in their pockets.

Deciding how many Americans we are willing to let die of COVID-19 each year is necessary to put the pandemic behind us.

With the COVID-19 study, it was clear that volunteers’ motives were overwhelmingly altruistic, said Carol Dalton, a spokeswoman for hVIVO, the clinical research company that carried out the COVID-19 study with scientists from Imperial College London. Participants earned 4,565 British pounds (about $5,500) for a 17-day hospital stay and several follow-up visits, though the pay was not a prominent feature of the hVIVO advertisements.

Separately, more than 38,000 people reached out to 1DaySooner, an online clearinghouse for people willing to participate in human challenge studies. Hopkins signed up on that website, as well as on the study’s official enrollment site.

“There was no precedent for so many volunteers asking scientists to put their own health at risk in such a trial,” said Abie Rohrig, a student of bioethics at Swarthmore College who helped set up 1DaySooner.

::

Hopkins took that risk in stride. He said he understood he was taking a chance, but he was more concerned about developing “long COVID,” an array of lingering post-infective symptoms, than he was about catching COVID-19 itself.

As he anticipated spending weeks holed up in St. Mary’s Hospital in London’s Paddington quarter, he had high hopes for using his time well. He thought he might learn British sign language online and stream some movies for fun.

But the schedule didn’t leave much time. Participants started each day in front of a laptop, churning through a battery of odious cognitive tests. There was also a daily “scratch-and-sniff” smell test and the hour he spent with his face buried in a plastic mask that measured his respiratory output. Research staff, often unrecognizable under layers of protection, were in and out of his room all day taking vital signs and drawing blood.

Meals were tasty but spartan. A bag of “crisps” showed up on his tray once or twice, prompting great excitement.

Strictly isolated in his hospital room, he gazed out the window at the London Eye, the city’s famous Ferris wheel, and lost himself in the reassuring nostalgia of classic video games like “The Sims” and “Ratchet & Clank.”

On two occasions, Hopkins was bundled into his own hazmat suit and wheeled to a CT scanner. “Those days were rare treats, when we were seeing something other than the four walls of a very sterile room,” he said.

If the U.S. public health emergency ends, Americans would be vulnerable to a new coronavirus variant that sparks another COVID-19 surge.

Getting the study underway took a year of debate and preparation. By the time British scientists deliberately infected Hopkins on March 2, 2021, several COVID-19 vaccines were beginning to go into arms across the United Kingdom. It was a milestone — but it threatened to derail the human challenge study, which had been intended to help with vaccine development.

“We had to completely rethink what this study was for,” said Dr. Christopher Chiu, an immunologist and infectious disease specialist who led the team from Imperial College London. With so much still unknown about the virus, “there was still a public health need,” Chiu said. And researchers testing antiviral medications would still need to know how much virus it took to seed an infection.

So the aim was recast. The trial would identify the exact dose at which an exposure to SARS-CoV-2 virus would infect half of healthy young people. And it would track the coronavirus’ behavior and its interaction with its hosts across the length of infection.

The study’s findings were reported this spring in the journal Nature Medicine.

Among its insights:

• Even at the lowest concentration measurable in a lab, SARS-CoV-2 virus established a beachhead in the throats of just over half of the young, healthy subjects within two days.

• The viral loads in their noses reached peak concentration an average of five days after exposure.

• Whether or not subjects developed COVID-19 symptoms, they were capable of infecting others for an average of five more days.

• None of the infected became seriously ill, but 83% lost their sense of taste or smell; in most cases, it returned slowly over three months. None experienced lung damage.

The findings made powerfully clear that young people have been potent drivers of pandemic spread. Further analysis of the findings is expected to yield insights into how the immune system resists infection, and why some people become infected while others do not.

So were these insights worth the risk taken by Hopkins and his fellow volunteers?

Chiu, the senior author of the paper detailing the study’s findings, thinks so.

“There’s unique strength to the findings from this kind of study,” Chiu said. “You capture every part of infection from the point of exposure to the end.”

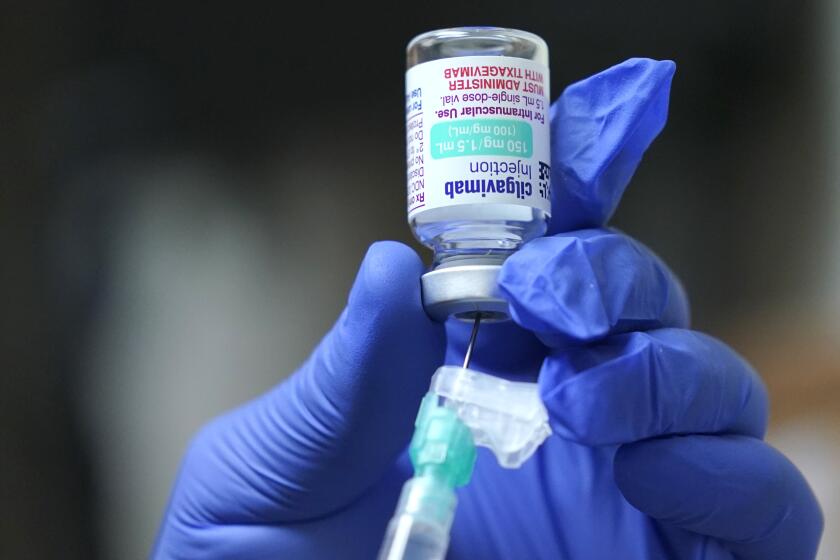

Evusheld can help protect immunocompromised people from COVID, but patients say scant awareness and a complicated process have hampered its rollout.

In the U.S., Caplan said he was frustrated that so much of the medical establishment was wary of allowing healthy Americans to be deliberately infected, when doing so could have yielded lifesaving insights.

People who sign up for such experiments must never be compelled to do so, Caplan said, nor induced with extravagant rewards. But people in many walks of life — from test pilots and deep-sea divers to virologists who collect bat guano from caves — take risks for science, he said. Every day, regular folks volunteer for early clinical trials of experimental drugs, where the correct dose is unknown and its safety is still very much in question.

“It’s a noble thing to do,” he said, adding that many Americans wanted to do it: “We knew because we’d been asked.”

::

Hopkins said he’d do it again, in a heartbeat.

Though the virus plunged him into a two-day ordeal of feeling “rubbish,” it was an enormous relief to realize he had become infected. After the tests he endured to get into the study, and after fending off so many COVID-19 surges, he finally had something to offer. He high-fived one of the doctors who dribbled virus down his nose.

During his entire bout, researchers tracked — hour by hour — the rise and fall of his vital signs, his viral loads, his altered cognitive state and his immune system’s strenuous effort to clear the virus.

When at last it did after 17 days, Hopkins received a check for 1,535 British pounds (nearly $1,900); the remainder was held in reserve pending follow-up visits.

“All I did was sat in a room,” said Hopkins, who now counsels low-income Britons on how to secure access to nutritious food. “But I was so proud and happy to be a part of this. I was really part of something special.”

On his last day at the hospital, as Hopkins slung his rucksack over his shoulder and marched toward the exit, the men and women who had taken his vital signs, delivered his meals and monitored his progress showed up to applaud him.

It was a hero’s farewell.