Drugs to fight Ebola may already be in your medicine cabinet, study suggests

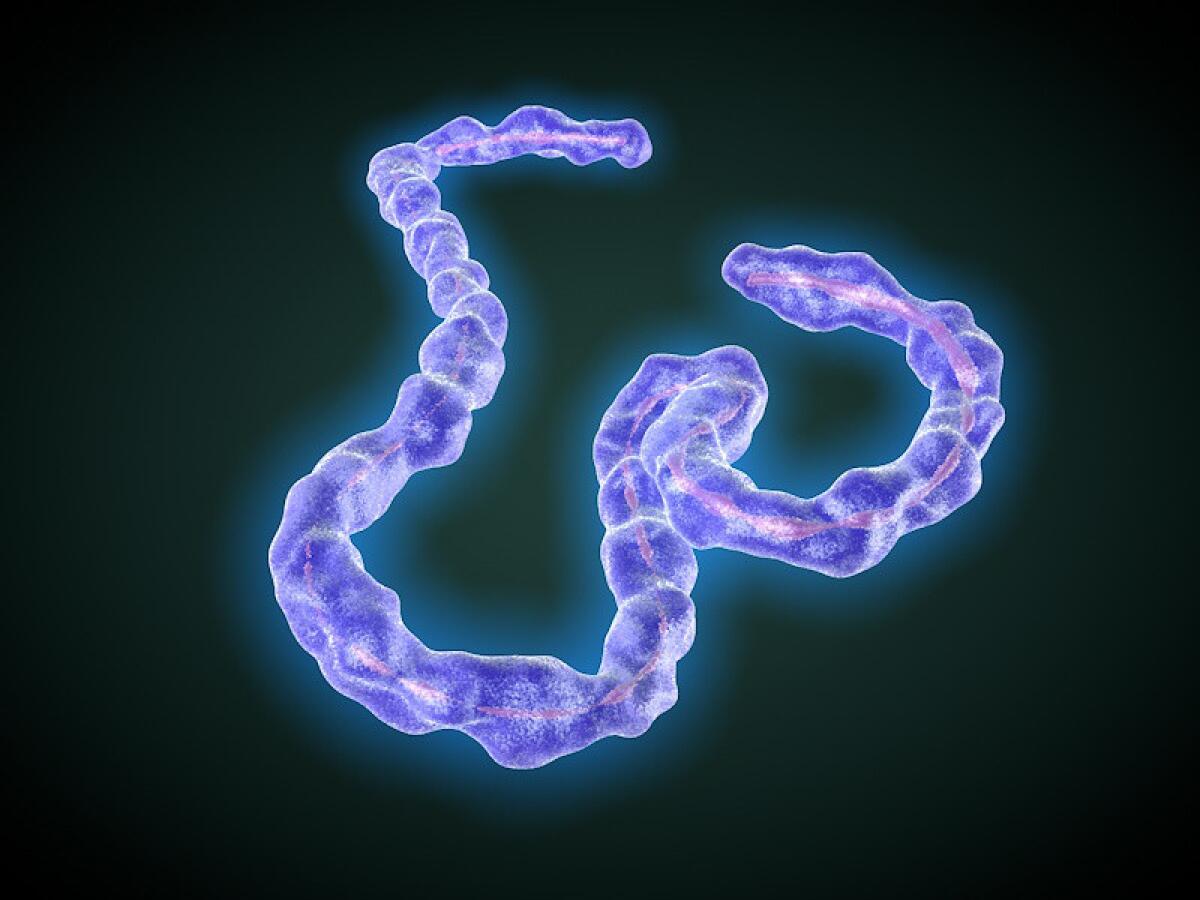

Researchers tested more than 2,600 compounds and found that two FDA-approved drugs, Zoloft and Vascor, were effective against the Ebola virus, shown.

- Share via

Researchers have found two drugs that saved the lives of mice infected with the deadly Ebola virus, and you may have them in your medicine cabinet already.

Zoloft, an antidepressant that has been on the market since 1991, cured 70% of mice that had the virus in their blood. Vascor, a heart drug that was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1990, cured 100% of the infected mice.

Zoloft and Vascor were just two of about 2,600 drug compounds tested for their ability to disable Ebola viruses and the closely related Marburg virus, according to a report published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine. Both types of viruses cause hemorrhagic fevers that can be fatal in up to 90% of cases.

The current Ebola outbreak in West Africa has killed 11,162 people and sickened 27,181 since claiming its first victim in December 2013, according to the World Health Organization. Researchers in government labs and pharmaceutical companies have been scrambling to develop new drugs to fight the virus, and while they have come up with several promising candidates, all of them have months or years of testing ahead of them.

A team from the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, the University of Virginia and Horizon Discovery Inc. of Cambridge, Mass., decided to take a different approach. Instead of creating a new drug from scratch, they set out to determine whether an existing drug could be deployed to fight Ebola.

They began with a “library” of 2,635 compounds that included FDA-approved drugs, amino acids, food additives, vitamins and minerals. Each of the candidates was tested on a version of the Ebola virus that had been engineered to glow green when exposed to ultraviolet light. A candidate was considered successful if it dulled the green signal by at least 40% and also did little or no harm to a sample of uninfected cells derived from the kidneys of African green monkeys.

A total of 171 compounds passed this first round of testing. From this list, the researchers picked 30 that seemed most promising and tested them further in the kidney cells and in human liver cancer cells. They found that 25 of the compounds were able to block Ebola’s entry into cells by more than 90%.

For the next round, the researchers picked eight compounds to test in mice. Drug treatment began one hour after the animals were infected with a mouse version of Ebola and continued for up to 10 days.

Three of the compounds had no discernible effect, and all of the mice who got them were dead within eight days. Three other candidates allowed 10%, 30% and 40% of the mice to live for 28 days.

But Zoloft (also known by the generic name sertraline) and Vascor (generic name bepridil) had more encouraging results. Of the 10 mice that got Zoloft, seven survived for 28 days. Even better, all 10 of the mice treated with Vascor were still alive 28 days after infection. For the sake of comparison, all of the untreated mice that served as controls were dead within nine days.

The two drugs were then tested in cell cultures against a larger group of Ebola and Marburg viruses. Both medications were able to fight all of the viral strains, including a Zaire Ebolavirus, the type now circulating in West Africa.

When an outbreak erupts, this type of research has the potential to get therapies in the hands of patients and healthcare workers much more quickly than inventing a brand-new drug, the study authors wrote.

“By repurposing approved drugs, in theory, one may reduce the risk, time and cost,” they wrote.

But the results so far are no guarantee that either Zoloft or Vascor (which has been discontinued in the United States) would be effective in a real-world situation, they added.

The drug concentrations tested in the study were higher than they are in people who take the medications as directed. It is not yet clear whether larger doses of Zoloft or Vascor would produce the necessary concentrations, or whether those concentrations would cause dangerous side effects.

Further testing is still needed, including trials in nonhuman primates, the researchers wrote. They added that they intend to do their part by continuing their work on Zoloft, Vascor and other promising compounds.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.