Coronavirus Today: A perilous pandemic for recovering alcoholics

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Monday, Feb. 8. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

We’ve talked about the long-term damage the coronavirus has inflicted on many victims’ health. But as the pandemic rages on, it’s become very clear that we need to keep watch for the lasting health effects not just of the virus, but of the pandemic itself.

Take the blow that COVID-19 has delivered to recovering alcoholics, sending thousands into relapse. Now, hospitals across the country are reporting dramatic increases in alcohol-related admissions for critical diseases such as alcoholic hepatitis and liver failure.

Liver disease linked to alcoholism was a problem long before COVID-19 hit. Some 15 million people were diagnosed with the condition across the country, and hospitalizations doubled over the last decade. The pandemic has now made that far worse. While national figures aren’t yet available, large hospitals around the country are already seeing a sharp rise in related cases.

Case in point: Admissions for alcoholic liver disease at Keck Hospital of USC were 30% higher in 2020 compared with 2019, according to Dr. Brian Lee, a transplant hepatologist who treats the condition in alcoholics. That parallels the accounts from specialists at hospitals affiliated with the University of Michigan, Northwestern University, Harvard University and Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, who all say admission rates for alcoholic liver disease have shot by up to 50% since March.

High alcohol consumption leads to a wide range of liver problems due to the toxic byproducts created as the body tries to break down the ethanol. In the short term, those byproducts can trigger enough inflammation to lead to hepatitis. Long term, they can result in the buildup of fatty tissue as well as the scarring seen in cirrhosis, which can cause liver cancer.

Because alcohol metabolism varies from person to person, these diseases can take years to manifest, or they can show up after only a few months of heavy drinking — and we’ve already had about a year’s worth of stress and isolation from the pandemic. Already, liver disease specialists and psychiatrists think the isolation, unemployment and hopelessness from the pandemic are fueling the skyrocketing number of cases.

“There’s been a tremendous influx,” said Dr. Haripriya Maddur, a hepatologist at Northwestern Medicine. Many of her patients “were doing just fine” before the pandemic, having avoided relapse for years. But subject to the stress of the pandemic, “all of the sudden, [they] were in the hospital again,” she said.

Some worrisome trends: The age of patients hospitalized with alcoholic liver disease has dropped across these institutions. Maddur, who has treated young adults hospitalized with the jaundice and abdominal distension that are characteristic of the disease, attributes the pattern to the pandemic-era intensification of economic struggles of younger folks, who are facing shrinking entry-level employment at the same time that they may be entering the housing market or starting a family. “They have mouths to feed and bills to pay, but no job,” she said, “so they turn to booze as the last coping mechanism remaining.”

Women may also be suffering from alcoholic liver disease disproportionately during the pandemic. That’s partly because they metabolize alcohol at slower rates than men, which can ultimately result in more extensive organ damage. But it’s not just the drinking itself. Women face lower wages and less job stability. Plus, the burdens of parenting tend to fall more heavily on women’s shoulders. Consider this: An analysis by the National Women’s Law Center found that all of the jobs lost this past December were women’s jobs.

“If you have all of these additional stressors, with all of your forms of support gone — and all you have left is the bottle — that’s what you’ll resort to,” said Dr. Jessica Mellinger, a hepatologist at the University of Michigan. “But a woman who drinks like a man gets sicker faster.”

And of course, there’s a vicious irony here: Alcoholic liver disease ultimately makes people more susceptible to COVID-19, and more likely to die of the disease.

It’s another way the pandemic is widening the inequities in our society that may, in the past, have been harder to spot. Perhaps making these gaps more visible will encourage experts to find ways to redress them — and help build a healthier society for all.

By the numbers

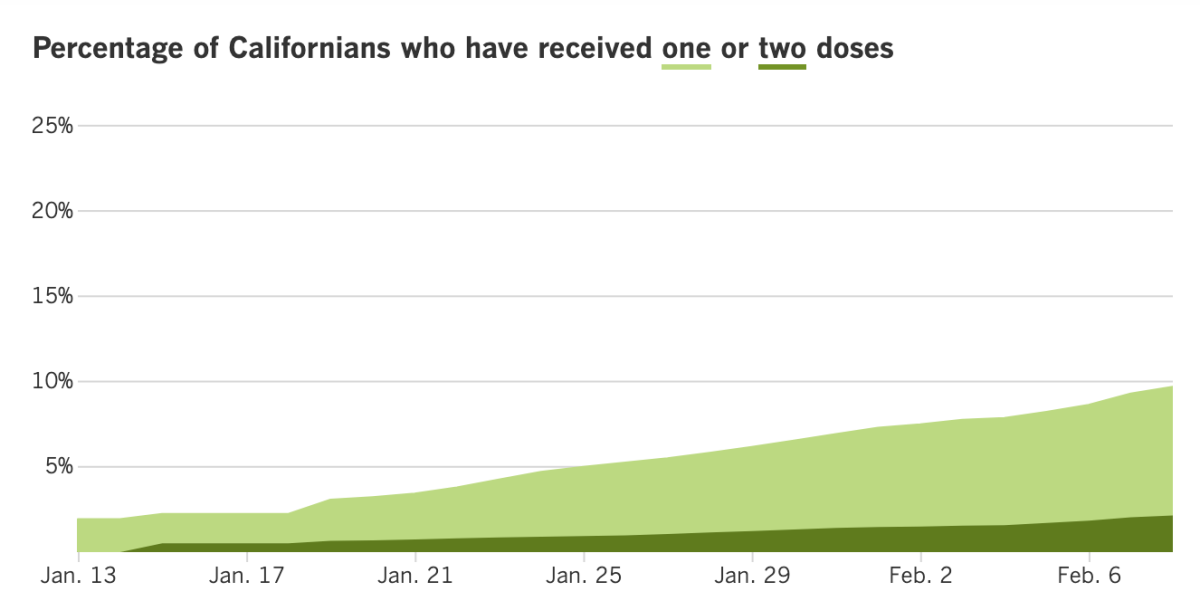

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:10 p.m. PST Monday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

Some good news in Los Angeles County, where daily coronavirus case numbers continue to fall. The county’s Department of Public Health said it logged 3,123 new cases and 89 related deaths on Sunday — some of the lowest numbers in recent days. The numbers of daily hospitalizations and the positivity rate have also declined steadily in the last week, though both those drops may be due partly to reporting delays.

Health officials are still worried about more contagious variants that are now circulating in Southern California, such as B.1.1.7, the more transmissible and possibly more virulent strain first identified in Britain. They’re also bracing for the possibility that Super Bowl gatherings may soon trigger another surge. And let’s not forget that cases, hospitalizations and deaths are still higher than pre-surge levels last year. More than 1.1 million confirmed cases have been logged in Los Angeles County so far, and the death toll is now above 18,000.

Los Angeles Unified Supt. Austin Beutner said Monday that vaccinating 25,000 teachers and staff could lead to the reopening of elementary schools for a quarter of a million students as soon as state guidelines allow, my colleague Howard Blume reports. At the same time, the L.A. schools chief again called for immediate access to immunizations for educators. Beutner stopped short of saying vaccines were a precondition for reopening, instead calling them “a critical piece to this reopening puzzle.” The L.A. teachers union, currently in negotiations with the district on reopening issues, has said that vaccines are a prerequisite to their return.

That target of 25,000 would include principals, teachers, bus drivers, custodians and librarians; as healthcare workers, school nurses already have access to vaccines. L.A. County officials are not yet allowing teachers to line up for shots unless they qualify under another category, such as those age 65 and older. The county health department has not indicated how soon teachers could start to get in the queue. With coronavirus case rates falling, L.A. County could soon hit the state-permitted threshold to allow for elementary schools to reopen.

In the meantime, vaccines may be in short supply in the county this week: An ongoing supply crunch and long lines of those in need of a second shot will likely leave few doses for those looking to begin the two-step immunization process, according to Dr. Paul Simon, chief science officer for the L.A. County Department of Public Health. There are two vaccines currently authorized for emergency use in the United States — one made by Pfizer-BioNTech, the other by Moderna — and both require two shots administered three and four weeks apart, respectively.

“We’re just struggling with the supply, the limited supply, and feeling an obligation to make sure that people that had a first dose are able to get their second dose,” Simon said.

While this may hopefully be a temporary bottleneck, some distribution centers say they’re getting squeezed harder than others. Take Clínica Monseñor Romero in Boyle Heights, a community clinic in a hard-hit Latino neighborhood that finally received a much-needed — but vastly inadequate — shipment of just 100 doses. The clinic serves 12,000 patients. “How is 100 going to take care of the 12,000 patients and the surrounding community of 1 million?” asked Dr. Don Garcia, the clinic’s medical director. “This is embarrassing.”

Carlos Vaquerano, the clinic’s executive director, said he was happy to receive the Moderna doses and understands the shortages. Still, he said the vaccines’ rollout has not been equitable. “It’s a matter of fair distribution,” he said. “We serve the most hard-hit community in Los Angeles. They are essential workers who are getting sick and are dying at a higher proportion than anyone else in the county.”

He’s right: For every 100,000 Latino residents in L.A. County, 40 are dying of COVID-19 per day (on average, over a two-week period). That rate is nearly triple that of white residents, who are experiencing an average of 14 deaths per 100,000 per day.

Some California churches reopened their nonvirtual doors for services on Sunday after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the state’s ban on indoor services during the pandemic appeared to violate the Constitution’s protection of the free exercise of religion. “This is not just our First Amendment rights, it’s really our biblical mandate not to forsake assembling with the saints,” Ché Ahn, senior pastor of Harvest Rock Church in Pasadena, told congregants during Sunday services.

A caveat: The high court said the state may limit attendance at indoor services to 25% of a building’s capacity, and singing and chanting may be restricted as well. San Bernardino and Ventura counties both said they would follow state guidelines and permit indoor church services at limited capacity. Orange County did not respond to a request for comment. L.A. County said that while it allows indoor church services, it encourages houses of worship to continue to hold them outdoors or virtually.

In the Bay Area, Santa Clara County officials said indoor services would continue to be banned there because their local health orders have a different framework than the state’s. “Santa Clara County, unlike the state, has never had rules specific to places of worship and has never closed places of worship,” County Counsel James Williams said. “Instead, we have across-the-board uniform rules that apply to gatherings of all types.”

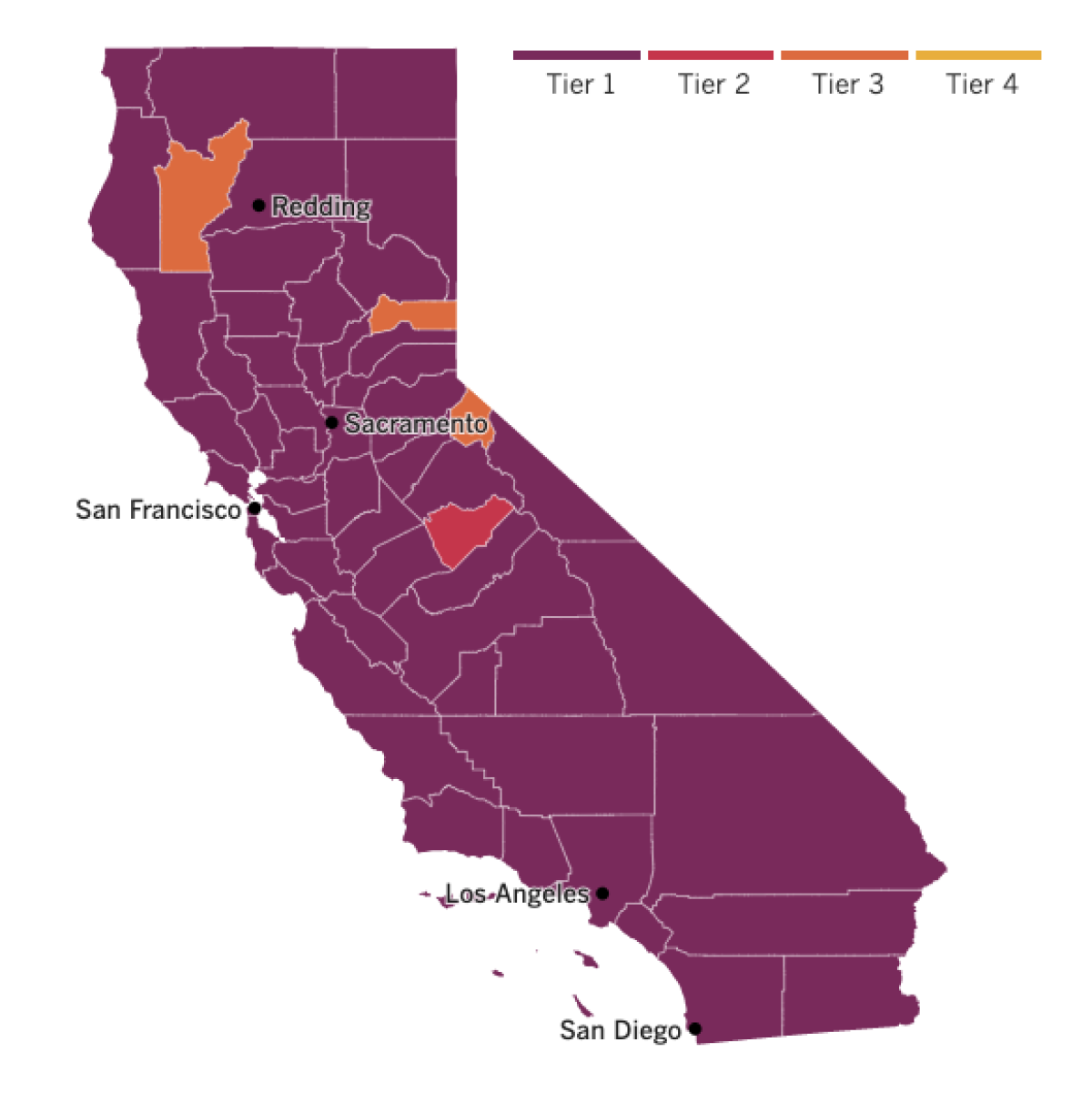

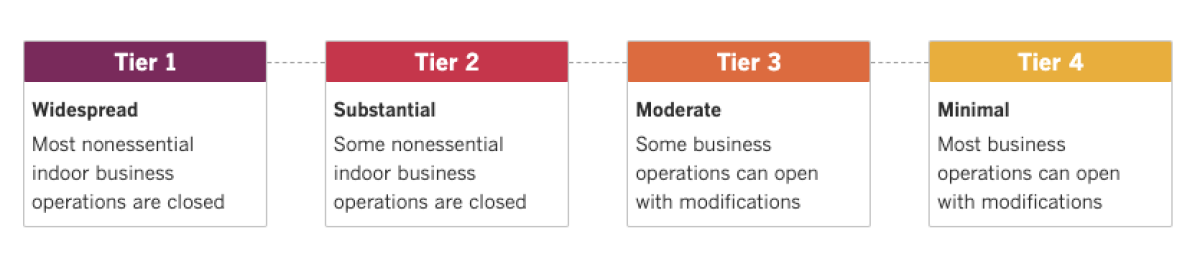

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

The Biden administration has launched an unprecedented push for genetic sequencing of tens of thousands of coronavirus samples from newly infected people in every state and territory of the U.S., and aims to build a program to plumb those data for insights into where the pandemic is heading next.

The centerpiece of the project — the new National SARS-CoV-2 Strain Surveillance, or NS3, program — will be tasked with detecting emerging variants of the virus in time to mount effective responses.

But that’s just the beginning. By allowing scientists to see the pandemic’s patterns of growth, genomic surveillance could help officials anticipate when new outbreaks will put stress on hospital capacity, where vaccination drives could cool hot spots and whether the rise of worrisome strains should dictate more stringent public health measures, my colleague Melissa Healy explains.

If carried out as intended, the initiative could take a technique that has so far been used to reconstruct outbreaks after the fact and use it to see around the pandemic’s next corner. It’s a capability that can’t come soon enough, researchers said. The U.S. needs to expand its capacity for genomic surveillance “rapidly and exponentially,” said Kristian Andersen, who directs a program of infectious disease genomics at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla. “The faster, the better.”

A California woman laid off due to the COVID-19 pandemic got a heck of a pep talk from the president himself. Michele Voelkert, 47, wrote Biden a letter after she lost her job at a start-up clothing company in July. He read it, then called her. The Roseville woman told the president that “it’s been a tough time” trying to find work.

Speaking from his Oval Office desk, Biden recalled his father saying that a job is about dignity and respect as much as it is about a paycheck. He described his $1.9-trillion coronavirus relief plan, which would give $1,400 payments to people like Voelkert, and offer other economic aid for individuals and small businesses — not to mention funds to help distribute COVID-19 vaccines. With Biden’s travel limited during the pandemic, the conversation was part of an effort to help him communicate directly with Americans, the White House said.

Across the U.S., more than 153,000 residents of nursing homes and assisted living centers have died of COVID-19 — making up an appalling 36% of the country’s pandemic death toll. Many of the 2 million people living in such facilities remain cut off from loved ones because of infection risk. But now there’s a glimmer of hope: Coronavirus cases in these settings have been dropping. It’s a welcome change that health officials are crediting to a range of factors, including the start of vaccinations, the receding of the post-holiday surge, better prevention measures and more availability of personal protective equipment.

Cases among residents fell by 48% at 800 nursing homes where initial vaccine doses were administered in late December. That compares to a 21% decline at nonvaccinated facilities nearby. And cases among employees dropped by 33% at vaccinated homes, compared to 18% at non-vaccinated facilities. “We definitely think there’s hope and there’s light at the end of the tunnel,” said Marty Wright, who heads a nursing home trade group in West Virginia. Health officials, however, warn that threats still lurk, including more contagious strains as well as reluctance by many nursing home workers to get their shots.

The coronavirus strain that’s fueling the latest outbreak in South Africa was not slowed down by the experimental vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and Oxford University. New results from a small clinical trial suggest that against the variant known as B.1.351, AstraZeneca’s shot isn’t effective in preventing mild to moderate illness. That’s bad news for the country, which had been counting on using the company’s doses to protect its front-line healthcare workers starting this month. “We have decided to put a temporary hold on the rollout of the vaccine,” Dr. Zweli Mkhize, South Africa’s health minister, said Sunday. “More work needs to be done.”

Scientists suspect that mutations in the virus’s genome have changed the shape of its spike protein, which is the vaccine’s primary target. This is a problem for several drugmakers’ experimental vaccines — including ones made by Johnson & Johnson and Novavax. Sarah Gilbert, who leads the Oxford team, said that she and her colleagues are making a tweaked version of the vaccine that targets the South African variant’s version of the spike. “It looks very likely that we can have a new version ready to use in the autumn,” she added.

It remains to be seen whether the AstraZeneca shot protects against the worst ravages that strain could cause — hospitalization and death. If so, the shot in its current form would still be useful. That’s something scientists will be studying, Mkhize said.

Tulio de Oliveira, an infectious-disease researcher at South Africa’s University of KwaZulu-Natal, pointed out that the situation with B.1.351 highlights the importance of “coming up with next-generation vaccines.” Such vaccines might be able to protect against new mutations by targeting sites on the virus that, unlike the spike protein, are less prone to change. “We’re beginning to know where a virus can mutate and where it can’t,” added Dr. Bruce Walker, an immunologist and director of the Ragon Institute in Boston.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: What’s the difference between a variant and a strain?

Now that the coronavirus seems to be releasing a new and unwanted mutation with flavor-of-the-week regularity, it’s a question on the minds of many folks trying to figure out how to navigate this complicated situation. My colleague Karen Kaplan offers an answer to this deceptively simple question.

It looks like virologists never got around to officially defining these terms, because there’s been confusion over the meanings of “variant” and “strain” since before the pandemic hit, Kaplan writes. Luckily, a pair of scientists tried to fill in the gap with a workable definition just last month.

The distinction between a variant and a strain hinges on whether the particular virus behaves in a distinct way, according to Dr. Adam Lauring, who studies the evolution of RNA viruses at the University of Michigan, and Emma Hodcroft, an expert on viral phylogenetics at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

“Genomes that differ in sequence are often called variants,” Lauring and Hodcroft explained in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. “Strictly speaking, a variant is a strain when it has a demonstrably different phenotype.”

A genome is a living thing’s genetic code. The phenotype is the sum of its physical characteristics and traits. When individual genes get tweaked in a virus as it replicates — a common and natural occurrence — it could result in a harmless mutation that results in no observable changes to its phenotype. That would make it merely a variant.

However, a mutation could result in a significant, and even dangerous, change. In that case, the variant has a distinct phenotype, and it would qualify as a strain. By this measure, both the South Africa and U.K. variants qualify as strains: the South Africa one because it’s less hindered by current COVID-19 vaccines; and the U.K. one because it spreads more readily than other variants.

There’s another definition for strain that comes from Nancy R. Gough, a scientist and editor who explains the biological world on her website, Bioserendipity. Accoording to Gough, a viral variant that becomes dominant in its population earns the right to be called a strain.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.