Coronavirus Today: Three big vaccine challenges

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Thursday, Dec. 10. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration could give emergency authorization to the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine as early as Friday, and clearance for the Moderna vaccine developed with the National Institutes of Health could soon follow. Now that U.S. regulators are close to authorizing not one but two COVID-19 vaccines, the big question for Californians is this: How are the shots going to reach us?

California’s first vaccine shipment will carry 327,000 Pfizer doses, enough to give 327,000 people the first part of the two-dose regimen. Depending on when authorization comes, that shipment is expected to reach hospitals between Saturday and Tuesday. Some 1.83 million additional doses — a mix of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s, which also requires two doses — should be reaching the Golden State by the end of the year.

All in all, by 2020’s end, California expects to have given a first shot to 2.16 million people in the priority inoculation group: healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities.

“Hope is on the horizon,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said.

All this sounds great, but getting there by years’ end — and administering millions more shots in 2021, once the vaccines are more widely available — will present a number of major logistical challenges.

Let’s take a look at some of them, and how officials are tackling three of the biggest ones.

— The vaccine is too cool. Once the vaccines arrive in state, they’ll have to be stored at locations that can accommodate the extremely low temperatures they need to remain viable. The Pfizer vaccine, for example, must be kept at about minus 70 degrees Celsius (or minus 94 Fahrenheit). Among those facilities: Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, UCLA and UC San Francisco Medical Center.

During the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic, L.A. County set up temporary sites to vaccinate many people at once quickly. But that will be more difficult because of the Pfizer vaccine’s temperature requirements. The county’s Department of Health Services has bought eight subzero freezers that altogether can store more than 1 million doses. In addition, the Department of Public Health acquired eight subzero freezers, which it will position strategically across the 4,000 square miles of L.A. County.

Moderna’s also needs be kept cold, but only at minus 20 Celsius, or minus 4 Fahrenheit — about the temperature of a regular freezer. That frees up more options for storing the vaccine in pharmacies or in rural areas without ultra-cold freezers.

— There’s not enough to go around (yet). A very small number of people will be able to get their first dose of the vaccine this year. Priority will go to health workers who are most likely to be exposed to the virus, along with the residents and staff of nursing homes and other long-term care facilities.

Keep in mind that even though the state is expecting to get 2.16 million first doses of COVID-19 vaccine by the end of the year, it’s still not enough to cover all 2.4 million healthcare workers in California.

— Who comes next? California officials have not yet determined who will be next in line for vaccines beyond the two current prioritized groups.

The federal panel that recommended that front-line healthcare workers and nursing home residents should be first in line also said that essential workers should get priority. But as my colleague Hugo Martín writes, that raises an important question: Who exactly counts as an essential worker?

Since early supplies will be limited, companies and industry groups are lobbying on behalf of their workers — including law enforcement officers, teachers, bus drivers, waste workers, meatpackers and farmworkers. Even Uber drivers and bank tellers are having arguments made on their behalf.

It will probably be spring or summer by the time vaccines are available for members of the general public who aren’t in a group that gets special consideration, said UCLA epidemiologist Dr. Timothy Brewer. “If I were planning a wedding for next summer, I would plan it in a way so that everything is cancelable,” he said.

Still, he thinks the U.S. could reach herd immunity, with 60% and 70% of the population vaccinated, by mid- to late 2021.

“I’m optimistic we will have a better Thanksgiving and Christmas next year than we did this year,” he said.

By the numbers

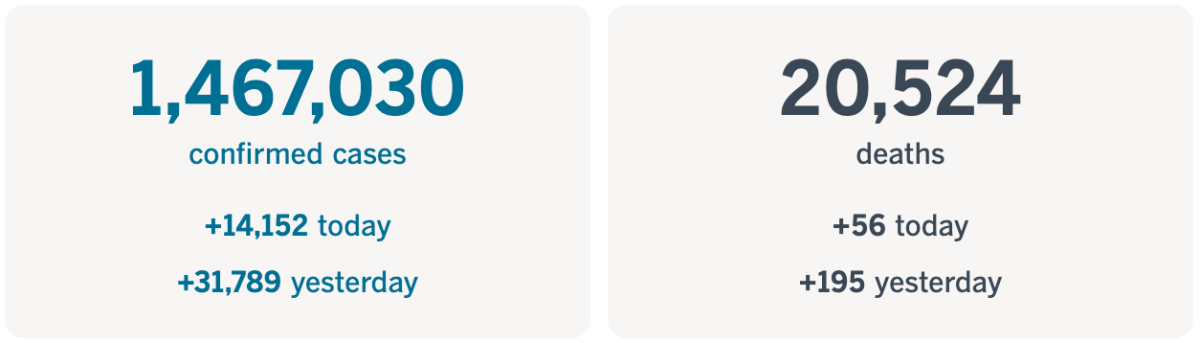

California cases and deaths as of 5:30 p.m. PST Wednesday:

Track the latest numbers and how they break down in California with our graphics.

Across California

COVID-19 deaths have climbed to record levels this week in California — “a grim sign of how even advances in medical care and a younger demographic of those infected are no match for the relentless spread of the coronavirus,” my colleagues Rong-Gong Lin II, Luke Money and Maura Dolan write.

By far the largest contributors to the Golden State’s death count are Southern California and the Central Valley. Of nearly 950 deaths reported in California in the last week, more than 300 were reported in L.A. County, followed by nearly 80 in San Bernardino County, about 70 each in Riverside and San Diego counties and nearly 60 in Orange County. While deaths are rising in Northern California, they haven’t come close to the numbers in the Southland.

“In all honesty, we never expected … we would be in this situation at this time of the year,” Dr. Muntu Davis, L.A. County’s health officer, said last month. “We were really hoping that we would be … by this time of the year, in November, getting our schools back open.”

San Francisco is facing a critical shortage of intensive care beds and is expected to run out in 17 days if the current rate of infection continues, the city’s public health director said Wednesday. “That is if things don’t get worse, and they very well may,” said Dr. Grant Colfax at a virtual news briefing, and he pleaded with residents to stay home.

The virus’s current reproductive rate in San Francisco is 1.5, which means that on average, every infected person will infect 1.5 other people. If that rate doesn’t come down, the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients will rise tenfold by early February, Colfax said. And models show an additional 1,500 residents may die on top of the 164 who already have.

“To be blunt, we have one chance to turn this serious surge around, and that chance is right now,” he said. “But our window is narrowing and closing fast.”

With the pandemic darkening our hopes, it may come as no surprise that many Californians are feeling pessimistic about the future. In a wide-ranging new survey, 6 in 10 said they expect California’s children to be worse off financially than their parents. More than two-thirds said the state’s gap between rich and poor is widening, and close to 6 in 10 expect “mostly periods of widespread unemployment or depression” during the next five years, my colleague Margot Roosevelt reports.

For what it’s worth, a UCLA economic forecast out this week took a far more optimistic view, predicting that the U.S. economy will experience “a gloomy COVID winter and an exuberant vaccine spring,” followed by years of robust growth. “The ’20s will be roaring, but with several months of hardship first,” the quarterly UCLA Anderson forecast predicts.

California’s recovery will largely look similar to the nation’s trajectory, according to the forecast. While the state’s October unemployment rate of 9.3% was significantly higher than the national rate of 6.9%, the California economy is set to grow faster than the U.S. after pandemic restrictions are lifted, the economists wrote.

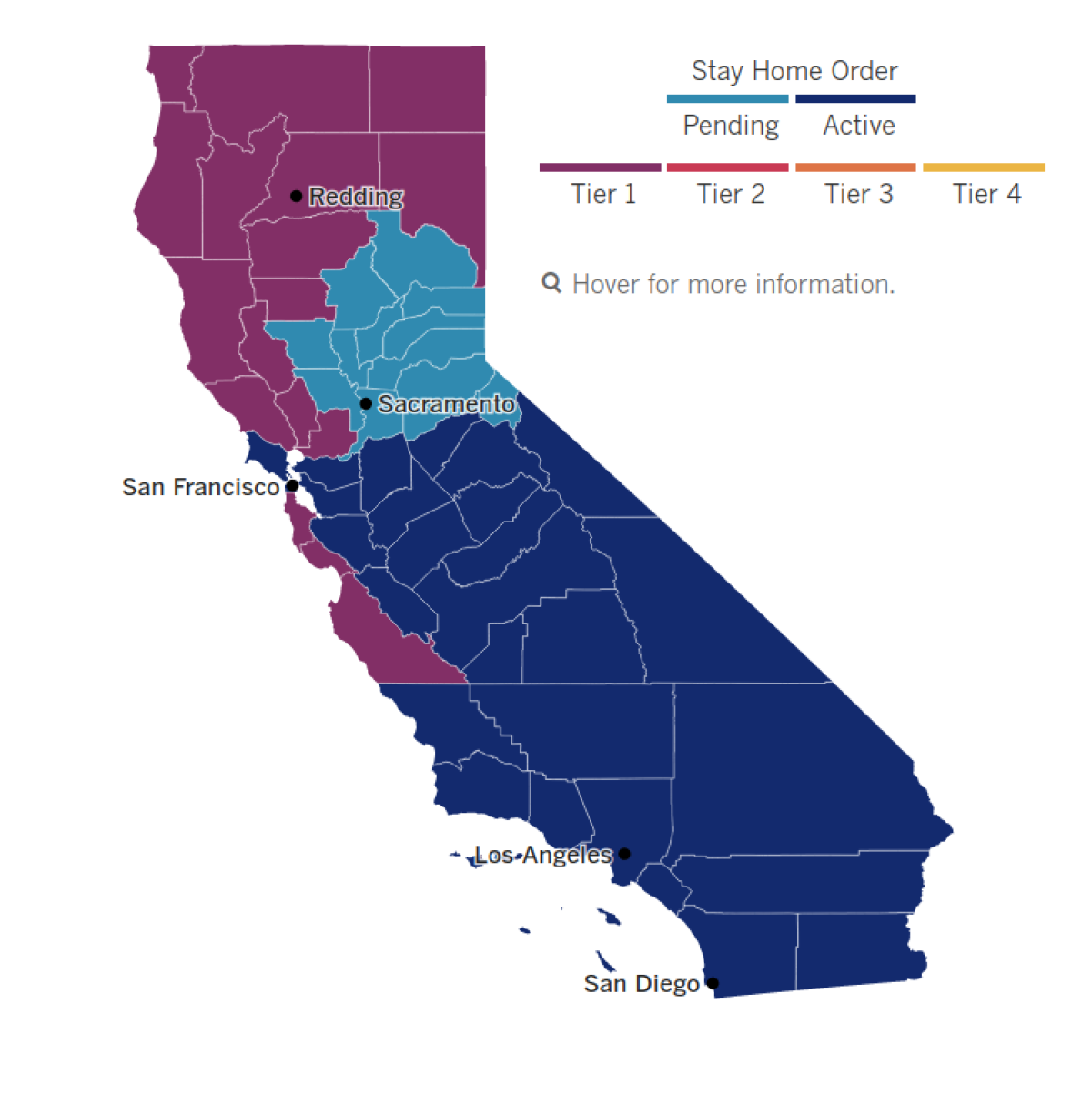

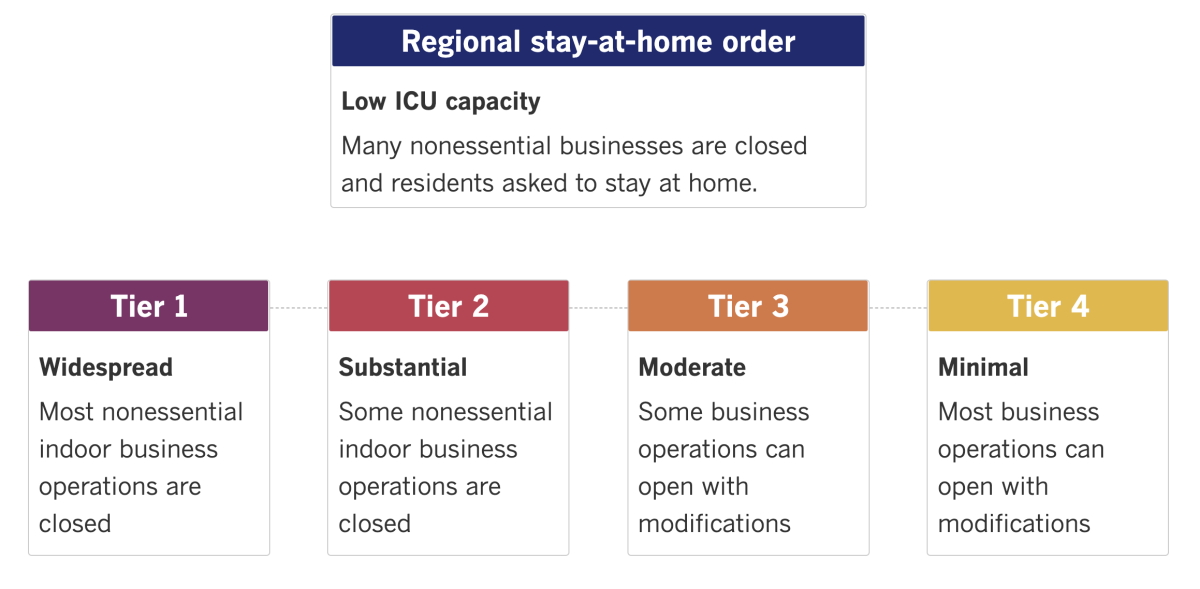

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

The U.S. may be seeing a glimmer of hope as it prepares to roll out a COVID-19 vaccine, but right now the pandemic feels darker than ever. Some 3,124 American deaths linked to COVID-19 were logged Wednesday — more than the death tolls from D-Day and from the 9/11 attacks. One million new coronavirus cases emerged in the span of just five days.

All in all, the pandemic has left more than 290,000 Americans dead, with more than 15 million confirmed infections nationwide. The crisis is pushing hospitals to their limits and burning out medical staffers and public health officials. St. Louis respiratory therapist Joe Kowalczyk said he had seen entire floors of his hospital fill with COVID-19 patients, sometimes two to a room.

New Orleans’ health director, Dr. Jennifer Avegno, watched doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists and others risk exposure in a long, futile attempt to save a dying COVID-19 patient. Some broke down in tears afterward, she said — seasoned emergency and critical care personnel who do not cry often, and certainly not all at once. She cited “the sheer exhaustion of giving their all for similar patients over and over and over again for the past nine months, coupled with the knowledge that much of this could be prevented with really simple measures.”

That message hasn’t sunk in in many smaller cities around the country, where arguments over mask mandates and other restrictions have turned ugly.

In Boise, Idaho, public health officials set to vote on one such mandate cut a meeting short Tuesday evening due to fears for their safety as anti-mask protesters gathered outside the building and at some of their homes. One had to rush home to her child because of the protesters, who were seen on video banging buckets, blaring air horns and sirens, and blasting a sound clip of gunfire outside her front door.

“I am sad. I am tired. I fear that, in my choosing to hold public office, my family has too often paid the price,” said the board member, Ada County Commissioner Diana Lachiondo. “I increasingly don’t recognize this place. There is an ugliness and cruelty in our national rhetoric that is reaching a fevered pitch here at home, and that should worry us all.”

Similar scenes played out across the nation, including in Sacramento County, where more than two dozen protesters pounded on the chamber doors during a debate over strengthening pandemic-restriction enforcement, and in South Dakota, where the Rapid City mayor said that City Council members were harassed and threatened over a proposed mask mandate.

Sweden took a lot of pride in its famously laissez-faire approach to the pandemic. Now, as the healthcare system nears capacity in many parts of the country, officials are rethinking that stance. COVID-19 has taken 7,300 lives from a population of just over 10 million. That’s roughly 26% more deaths than North Carolina, whose population is roughly the same size. The country also has a higher mortality rate among those who do get sick from the virus.

“This is exactly the development we didn’t want to see,” said Björn Eriksson, the healthcare director for greater Stockholm. “It shows that we Stockholmers have crowded too much, and have had too much contact outside of the households we live in.”

Up to now, Sweden had put out largely voluntary guidelines, encouraging citizens to practice social distancing and wash their hands — but not to wear masks, which many health officials around the world say are a key defense against spreading the virus.

Restrictions announced last month now limit public gatherings, both indoor and outdoor, to eight people — down from 50 — and ban the serving of alcohol after 10 p.m. in bars and restaurants. High schools are moving to distance learning. And this week, the government proposed giving authorities more power to close down shops, restaurants, gyms and other gathering places.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from a reader who wants to know: Do you need to wear a mask after recovering from COVID-19?

This question comes from someone whose 9-year-old daughter has a friend who had COVID-19 a few weeks back and has since recovered and tested negative. She told the reader’s daughter that because she’s had it, she doesn’t need to wear a mask when the two children play.

The experts I’ve spoken with say this isn’t true. Even those who have recovered from COVID-19 should wear a mask around other people for two reasons.

Take the case of Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who quarantined after being exposed to an infected colleague even though Johnson had himself already had COVID-19.

Dr. Stuart Ray, an infectious-disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, explained the reasoning in a previous newsletter.

First: People who have already survived COVID-19 can potentially be reinfected if they’re exposed to a different strain of the virus from the one that initially made them ill. Due to a lack of testing, it’s hard to know how often this happens. But scientists have documented cases around the world, including one in Nevada.

Second: Scientists think that roughly half of coronavirus transmission happens through people who show no signs of the disease. So you never know where a different strain might come from.

Since you can’t assume a COVID-19 survivor is immune to reinfection, either one of you could still expose the other to the virus. That means you should both wear masks.

For the time being, experts say, there’s no free pass to unmask.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask. Here’s how to do it right.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Updates

2:07 p.m. Jan. 20, 2021: In the “Your Questions Answered” portion of this newsletter, we may have implied that a person who recovered from COVID-19 could be sickened again only if they’re exposed to a different coronavirus strain. While that can happen, people can also be reinfected by the exact same strain — though because of testing limitations, it’s impossible to say how often this takes place. Want to learn more? Check out the reader question in this edition of Coronavirus Today.