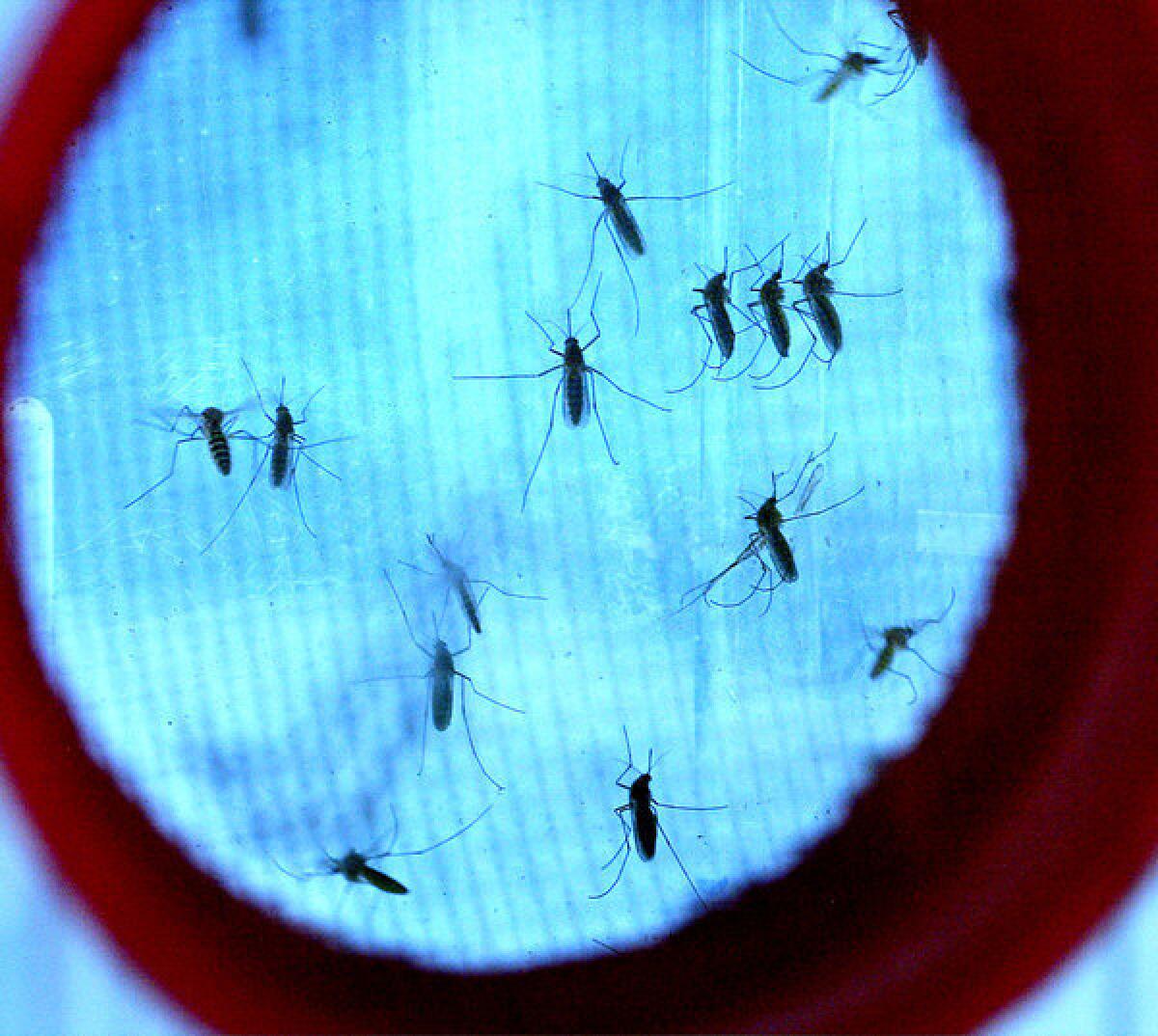

Mosquito monitoring can prevent West Nile outbreaks, study says

- Share via

About 100 cases of West Nile virus infection -- and a dozen deaths -- could have been prevented last year if public health officials in Dallas had kept track of the proportion of infected mosquitoes caught in traps, a new study says.

A detailed analysis of the 2012 outbreak in Dallas gave researchers the perfect opportunity to test a long-held theory that monitoring mosquitoes, rather than human cases, could predict epidemics and allow for early intervention. Keeping tabs on mosquitoes allows public health officials to estimate the rate of infection in the local mosquito population, as well as the mosquito population size; multiplying the two numbers produces a figure called the “vector index.” Experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention thought the vector index would make it easier to see where the virus was spreading and take early action to slow or halt that spread.

West Nile virus, which is most commonly transmitted by mosquitoes, can cause fever, encephalitis and meningitis, according to the CDC. Although most people who are infected won’t display symptoms, about 1 in 5 will develop a fever with other symptoms. Less than 1% of patients will develop a serious, sometimes fatal, neurologic illness. Currently, no medications or vaccines for the virus exist.

The virus first emerged in New York City in 1999. It then spread across the U.S, with the first outbreak in Dallas occurring in 2006. After a five-year lull, the virus came roaring back in 2012, infecting 7.3 out of every 100,000 residents and killing 19 people.

Dr. Robert Haley, an epidemiologist with UT Southwestern in Dallas, and his colleagues calculated the vector index for each week during the 2012 epidemic. Frequent monitoring is crucial, because symptoms normally take a week to appear and subsequent lab tests can take another two to three weeks to produce results. By then, the epidemic would have almost finished running its course.

“It can take three or four weeks before you know about people who are infected,” said William Reisen, an epidemiologist at UC Davis who was not part of the study. “By that time, there are that many more infected, and you’re far, far behind.”

Based on those figures, they used statistical models to determine that Dallas public health officials could have prevented 100 cases and 12 deaths had they intervened a week after the vector index hit its threshold. Instead, they took action only after several patients had been hospitalized.

Weather conditions in 2006 and 2012 created “a perfect storm” for a West Nile epidemic, Haley said. Within the 11-year period studied, both years had the fewest hard freeze days — when the temperature low measured less than 28 degrees Fahrenheit — and the warmest spring temperatures. Both years also saw drought punctuated by rainstorms “so there was always a little standing water around,” Haley explained.

Experts say that global warming trends forecast more epidemics. “Diseases that typically only occurred in the tropics are starting to creep northward,” Haley said. “West Nile is one of them.”

Merging surveillance with Census tract data, the researchers also found that, in both the 2006 and 2012 epidemics, cases tended to cluster around affluent, housing-dense areas with a higher percentage of unoccupied homes — not in low socioeconomic neighborhoods, as often occurs with other urban epidemics.

Haley explained that the abundance of housing in these hotspots might have provided a more hospitable environment for the common house mosquito, which carries the West Nile virus, than poorer Dallas neighborhoods, which attract less development.

“The Dallas study is a very cogent reminder that the virus is certainly still here and it’s still capable of causing a very significant public health problem,” said Dr. Stephen Ostroff, an epidemiologist at the Pennsylvania Department of Health who wrote the editorial that accompanies Haley’s study. “You don’t want to take your eye off the ball.”

Ostroff added that preventing and controlling the virus requires “an integrated vector management approach” that involves identifying potential breeding sites in the winter and spring, well before mosquito season hits. Regularly cleaning clogged gutters and maintaining swimming pools would eliminate many breeding sites, he said. Mosquito monitoring and targeted pesticide use are also key.

“It’s the proverbial ‘an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,’ ” he said.

Haley cautioned that his group’s findings may not apply to regions outside of Dallas, adding that the CDC recommends that each region conduct a similar study to begin developing their own prevention program. “This paper gives them ideas,” Haley said. “They can follow along and do some of the same types of things.”

In the editorial accompanying the study, Ostroff warned against complacency among policymakers and the public, which he partly blamed for the delayed response to the Dallas epidemic in 2012. Federal funding for the CDC Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity program, which distributes funds to states and some large cities for mosquito surveillance and disease prevention efforts, peaked at $35 million with the emergence of West Nile in 2000, but dropped to less than $10 million by 2012, he wrote.

But policymakers should also “invigorate” treatment options, Ostroff said, adding that almost 15 years after the first West Nile outbreak, no human virus vaccine, specific treatment, or method to disrupt the transmission cycle has been developed.

Twitter: @mmpandika