At Mt. Wilson, scientists celebrate 100th birthday of the telescope that revealed the universe

- Share via

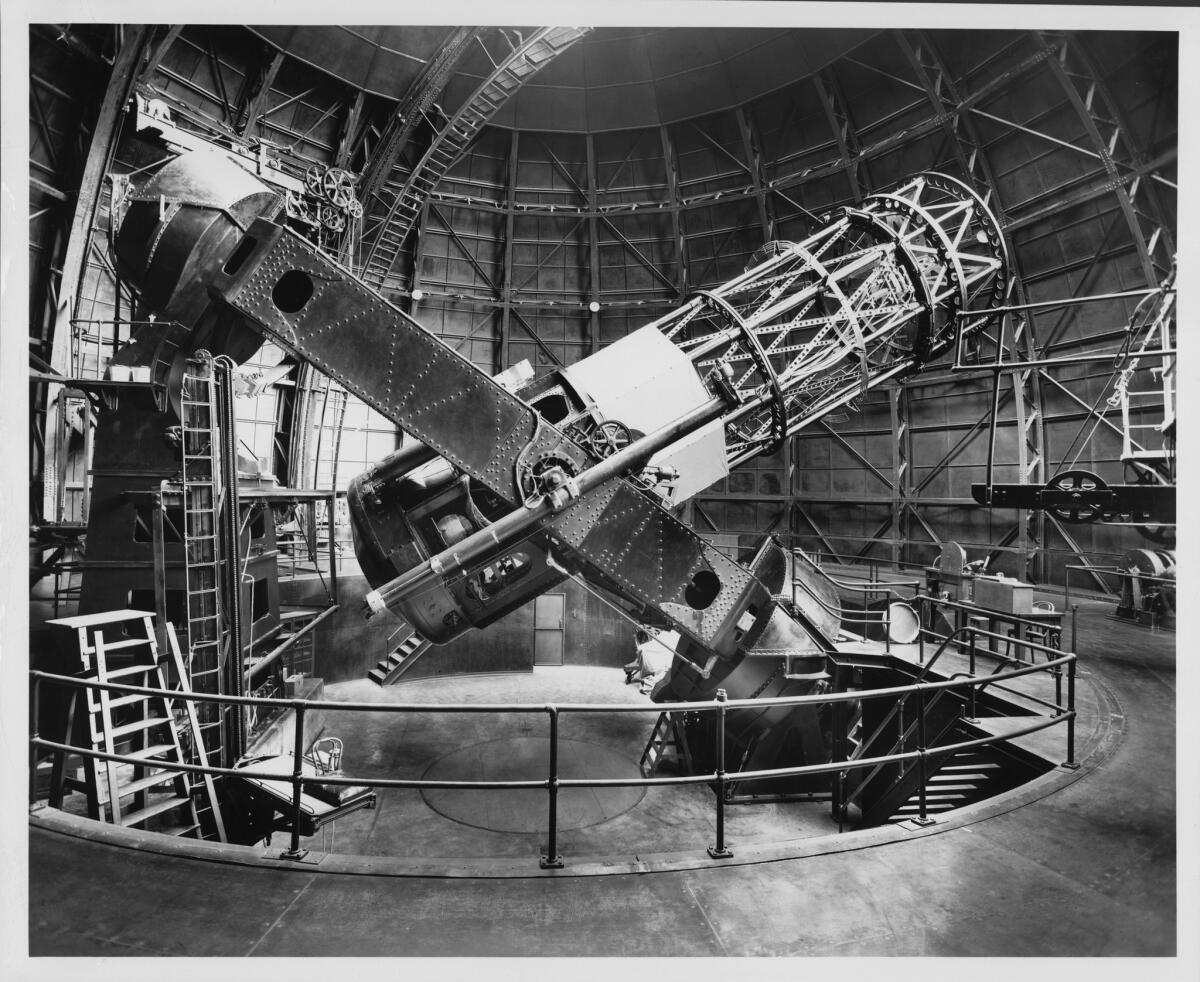

Beneath the cavernous, rivet-studded dome of the Mt. Wilson Observatory, dozens of people gathered around the 100-inch telescope to take a peek at the craters and crags of the moon. Later, the telescope swiveled toward the double star Albireo and the Blue Snowball nebula, revealing the ghostly objects in breathtaking detail.

Thomas Meneghini, executive director of the Mt. Wilson Institute, never tires of these nights.

“I get to operate this,” he said Saturday evening, gesturing at the telescope that dwarfed the crowd below. “I just get a thrill out of it.”

Wednesday marks the centennial of the 100-inch Hooker telescope. When it gathered its first light on Nov.1, 1917, it overtook its 60-inch neighbor and became the largest telescope in the world — a position it held for more than three decades.

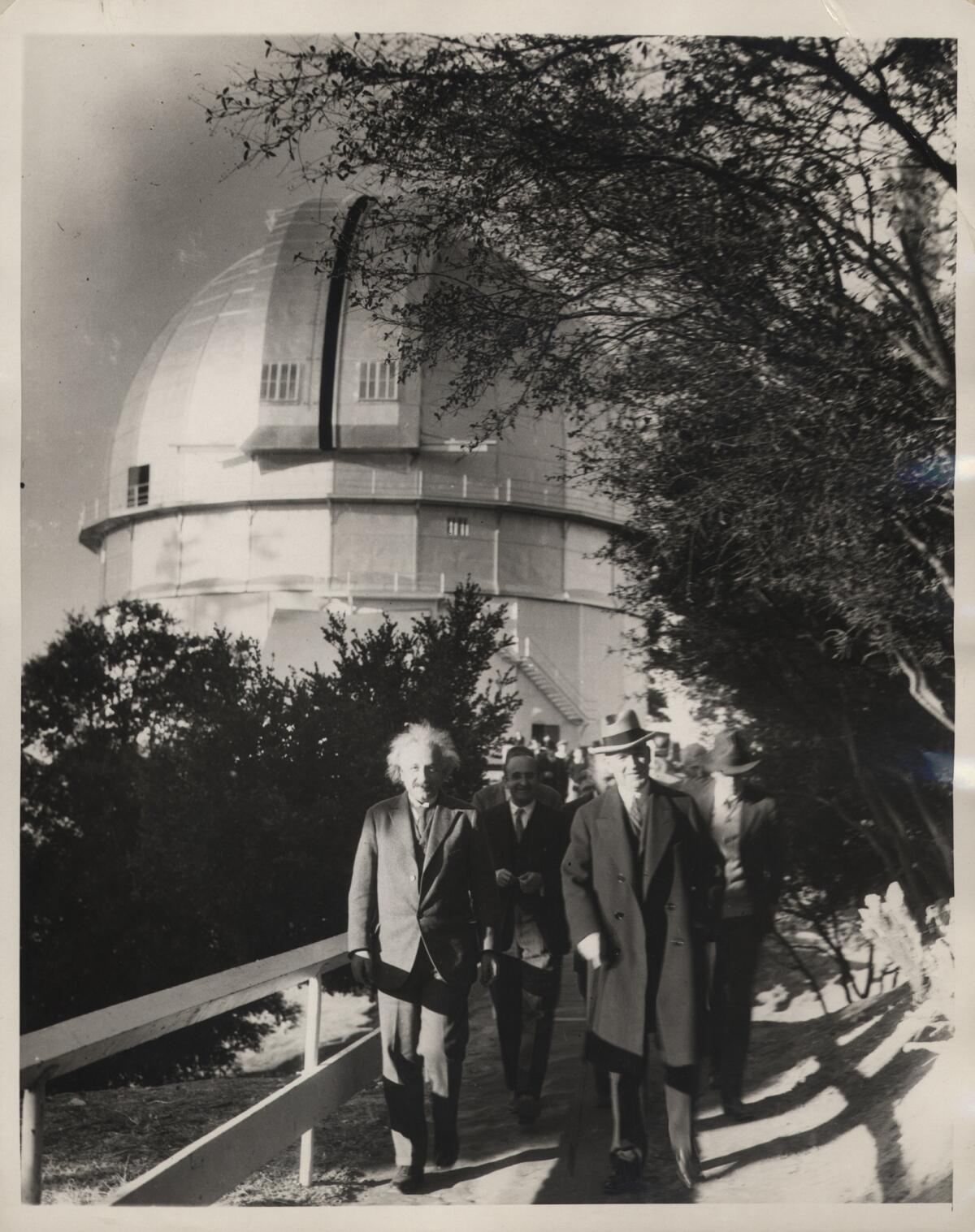

Here in the San Gabriel Mountains, astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered that the universe existed far beyond the edges of the Milky Way galaxy. Later, with a former mule driver named Milton Humason, he discovered that the universe was not static, but was in fact expanding.

“In some ways, I consider Mt. Wilson Observatory to be the most important optical observatory in the history of astronomy,” said Alex Filippenko, a UC Berkeley astronomer who helped determine that this expansion is accelerating, driven by the existence of a mysterious force called dark energy.

“It was really an amazing instrument to use,” added Filippenko, who as a

A cosmic shift

Before the Mt. Wilson Observatory was built, astronomers were largely concerned with the positions of the stars in the sky, not what they were made of, said George Preston, director emeritus of the Pasadena-based Carnegie Observatories, which includes Mt. Wilson.

Back then, aside from the Lick Observatory in the Bay Area and a handful of others, large telescopes generally sat on or near a university campus, which placed them close to sea level. This meant they could be easily clouded out; even on a clear night, the layers of atmosphere distorted the starlight.

George Ellery Hale tried a different approach.

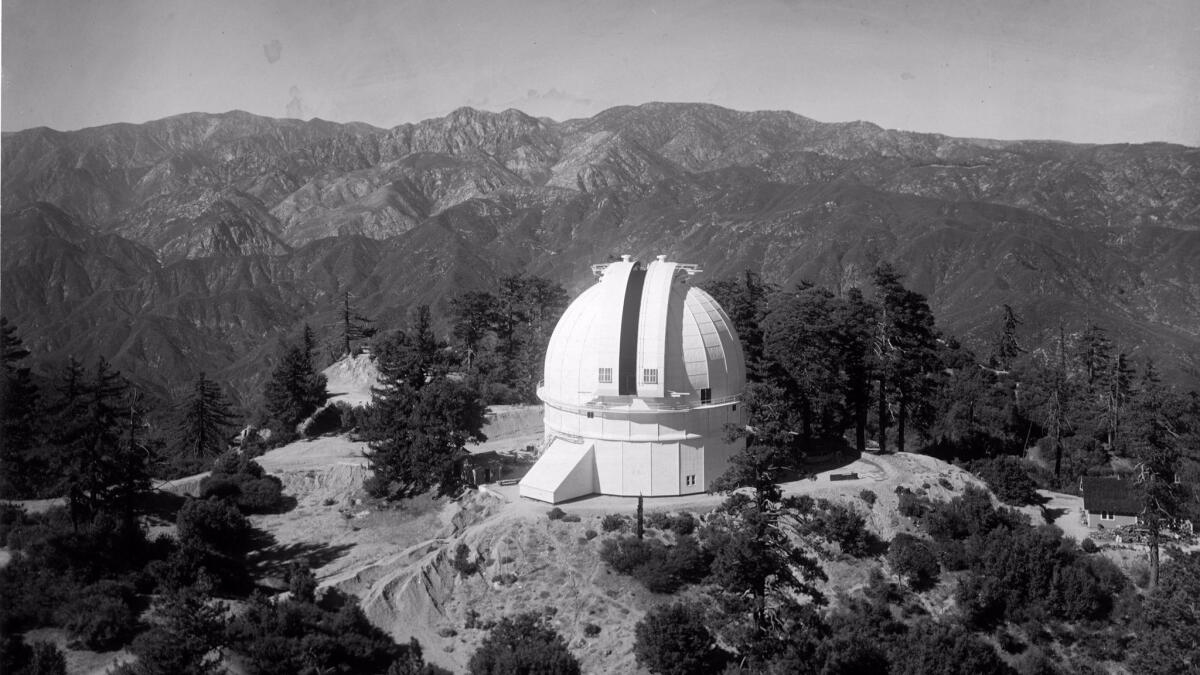

Hale had previously led the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin, a low-lying telescope surrounded by farmland. This time, he wanted to build a large telescope high on a mountain, above the clouds and much of the air. He also hoped to create an observatory that was something of a laboratory, complete with spectrometers to break up the incoming light and reveal its chemical fingerprint.

After erecting solar telescopes on the mountain, Hale built a telescope with a 60-inch-wide mirror some 5,700 feet above sea level in 1908. Two years before it was even finished, he started work on a second telescope there with a 100-inch mirror. (It was named after Hale’s friend John D. Hooker, a local businessman who donated $45,000 to the effort.)

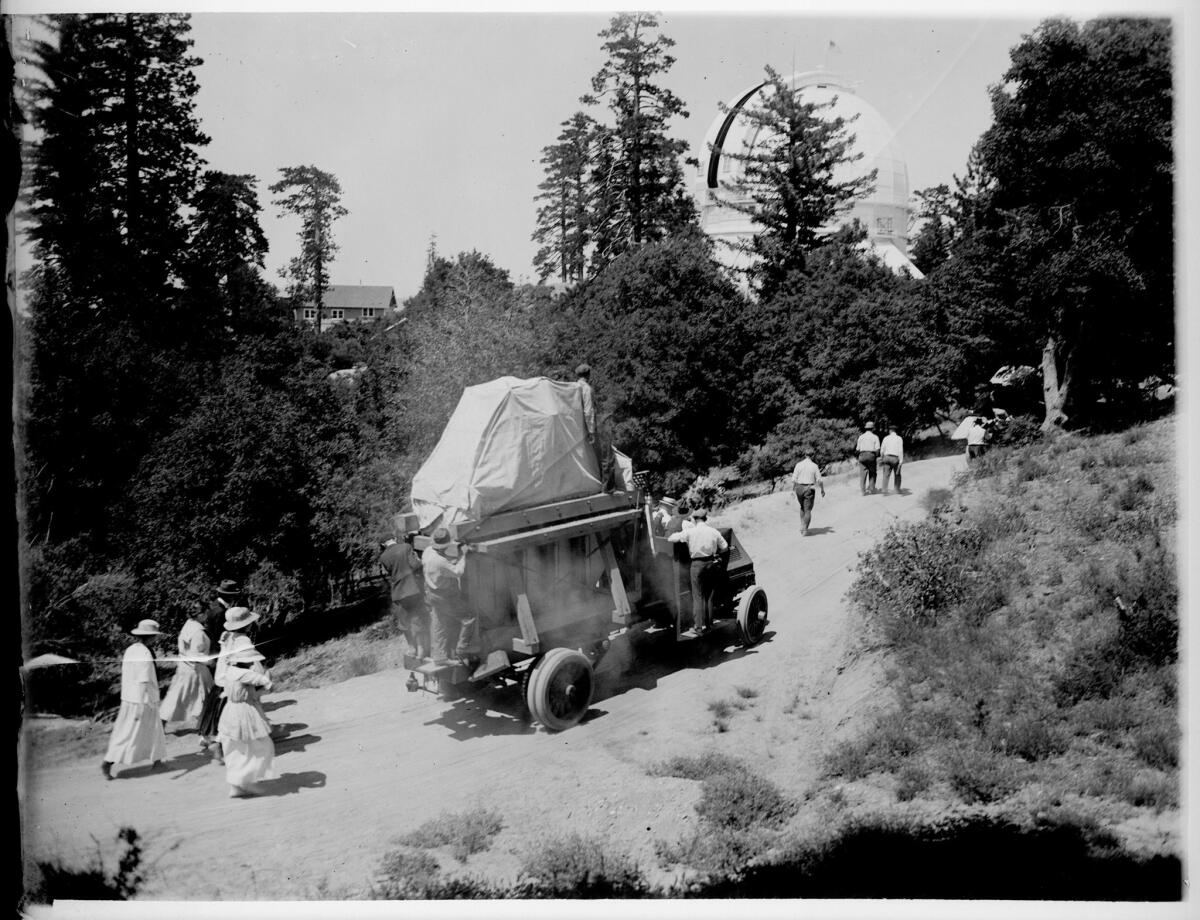

Building on such a high mountaintop was easier said than done. During construction, components of the larger telescope were dragged up the winding mountain road at a blistering pace of 2 miles per hour.

The heart of any telescope is the mirror. Its large area collects the starlight, and its slight curvature helps to focus it. Bigger mirrors often mean better images — unless the mirror has flaws.

The 100-inch mirror for the Hooker telescope was cast in France and was transported to Pasadena by way of New Jersey and New Orleans. When it arrived, Hale immediately saw that the glass had been poured in layers, with bubbles visible between each one.

He ordered a replacement, but it was not meant to be. The second attempt in France broke the mold. On the third try, the glass broke while cooling.

Running low on funds, Hale resigned himself to using the original mirror.

On the night of Nov. 1, 1917, Hale and several other notable astronomers gathered as the telescope was turned on for the first time. They trained it on Jupiter, expecting to see it rendered with impeccable clarity — and were dismayed to find that the image was a blur.

Something was wrong. The researchers realized a worker had left the dome open. Perhaps the sunlight had heated the mirror, temporarily distorting it.

They decided to give the machine a few hours to cool down and try again. In the meantime, they tried, in vain, to get some sleep.

Sure enough, around 2:30 a.m., they pointed the telescope at a bright star. It worked.

“I can’t even imagine how nerve-wracking that must have been,” said Cynthia Hunt, chair of the History Committee for the Carnegie Observatories.

Astronomy in action

Operating a telescope in those days was difficult, and sometimes dangerous, work.

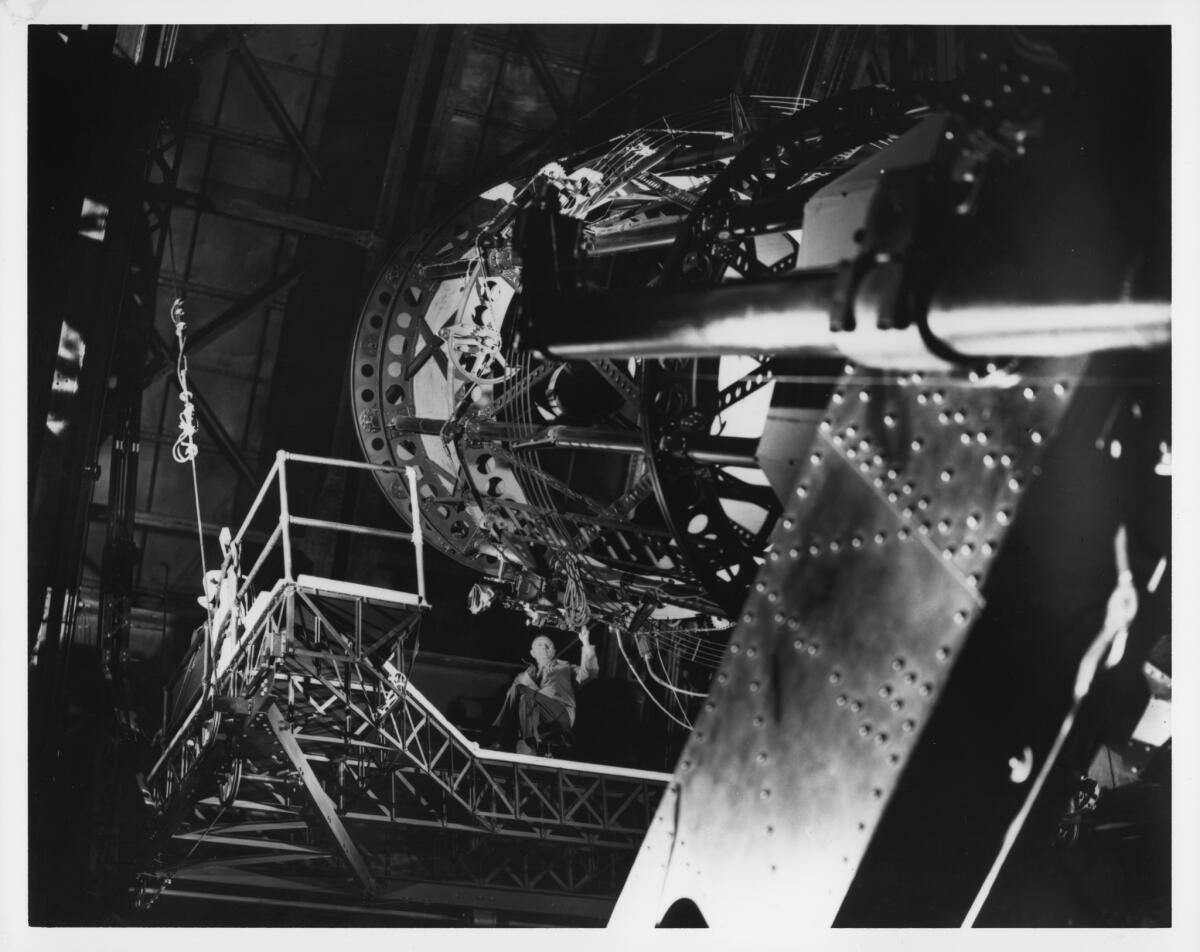

Astronomers often wore thick fur coats on cold winter nights, and kept pots of coffee close by. They perched on high platforms as they peered into the heavens, carefully adjusting the telescope minute by minute for hours as the stars crept across the sky. At times, they were exposed to mercury, a toxic, liquid lubricant that kept the telescope moving smoothly.

In the 1940s, an astronomer, Alfred Joy, fell roughly 30 feet from one of the platforms, breaking several bones.

“He recovered and limped forever after that,” Preston said.

Preston, 87, directed the observatories from 1980 to 1986. He first came to Mt. Wilson as a college student, falling in love with astronomy over the course of a summer.

He returned a few years later as a postdoctoral researcher. Working with the 100-inch telescope was liberating, he recalled.

“For the first time in my life, I was free,” Preston said. “Nobody was telling me what to do.”

A new purpose

As Los Angeles grew and its city lights brightened, the telescope’s ability to probe the distant heavens dimmed.

Hale had long since moved on to a 200-inch telescope at Palomar Observatory in San Diego County. Funding was drifting to more modern telescopes in better locations.

In the 1980s, the money for Mt. Wilson finally dried up.

But there were some devotees who did not want to see the telescopes mothballed for good. A few years later, the nonprofit Mt. Wilson Institute took over from the Carnegie Institution for Science, which still owns the observatory.

Volunteers now manage the telescopes, and the institute sells telescope time to private groups and provides educational tours for local schools.

At the star party last weekend, Samuel Hale stood under a string of lights outside the observatory and considered what his grandfather George would have thought of the celebration.

“He wouldn’t be here today,” said Hale, a Santa Barbara resident who serves as chief executive of the Mount Wilson Institute. “This is wonderful, but he’d be on to the next thing.”

Regardless, Hale stressed both the 60-inch and 100-inch telescopes remain deeply valuable — as historical monuments, and as educational tools that could inspire new generations of astronomers.

“In that way we really are looking toward the future, like he would,” Hale said. “It’s just another avenue.”

Follow @aminawrite on Twitter for more science news and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

How your brain processes certain words can help predict your risk of suicide

More ink, less water: News coverage of the drought prompted Californians to conserve, study suggests