News Analysis: A week late, Democratic candidates wake up to Sanders’ potential to beat them all

- Share via

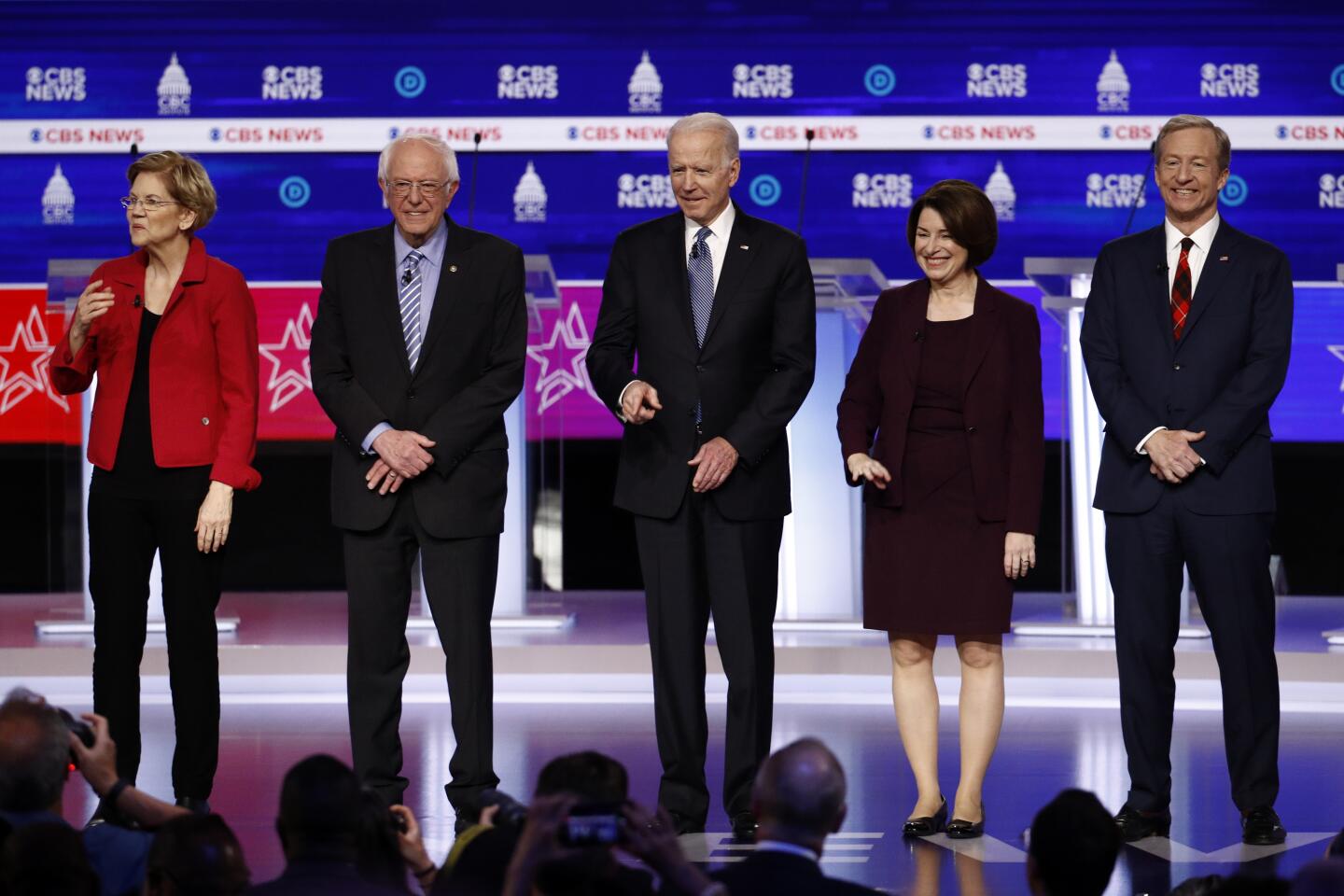

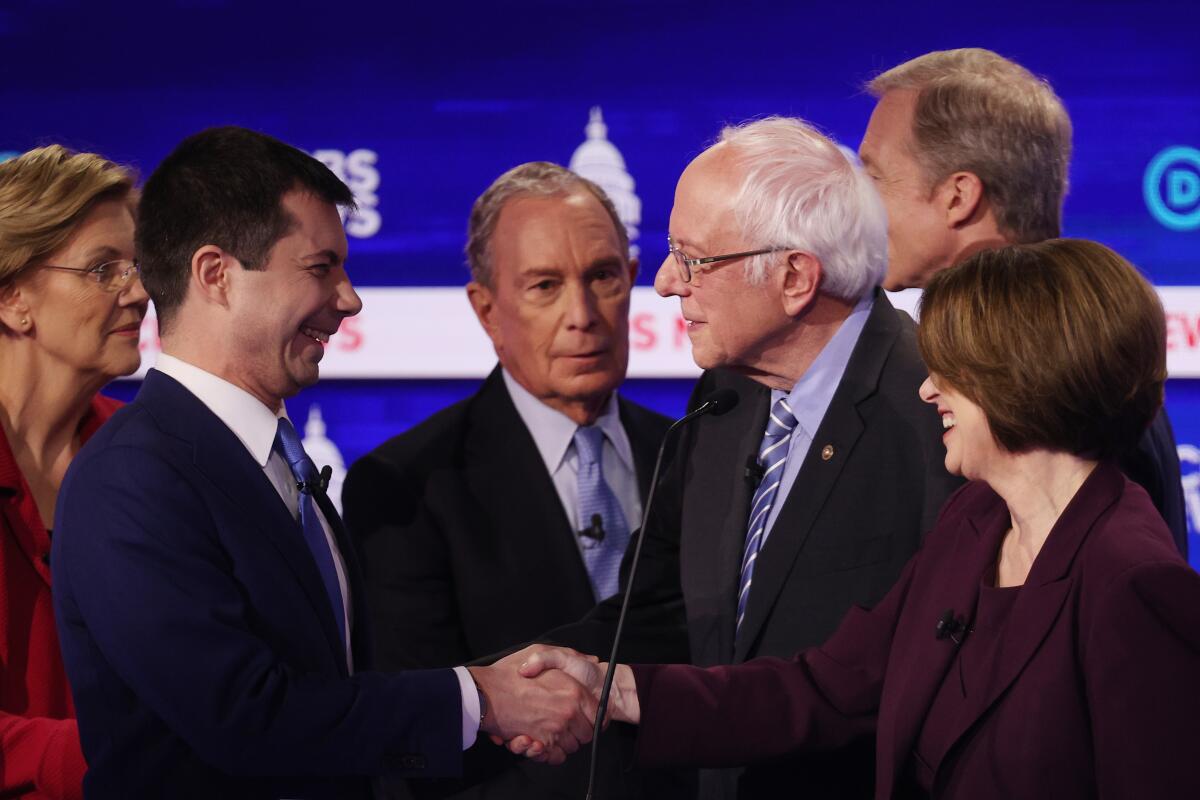

An air of desperation suffused the Democrats’ presidential debate almost from its first moments Tuesday night as six of the candidates confronted a reality they had previously tried to wish away: The seventh, Sen. Bernie Sanders, was on the verge of beating them all.

As recently as their last debate less than a week ago in Las Vegas, most of the rivals treated Sanders gingerly and focused their fire on former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg. Sanders responded by clobbering his rivals in Nevada’s caucuses and pouring resources into Saturday’s primary in South Carolina and next week’s 14-state Super Tuesday contests with a goal of putting a swift end to the nomination fight.

Having come close to booting away the prize most of them have spent more than a year pursuing, the other Democrats lost little time Tuesday in making clear that Sanders — his positions, his judgment and his experience — would be the prime topic of the night.

But while their efforts gave the debate plenty of passion, and may have planted doubts in the minds of some voters toying with supporting the Vermont senator, they did nothing to resolve the biggest problem the non-Sanders candidates face: Too many of them have stayed in the race too long.

Sanders began this year’s campaign with one great strength — the loyalty of his supporters on the party’s left, many of whom backed him in his campaign against Hillary Clinton four years ago. That backing has never wavered and has allowed him consistently to win the support of somewhere between a fifth and a quarter of Democratic voters.

In a two-person race, support from one quarter of the voters is a recipe for failure. But as President Trump showed in his race for the Republican nomination in 2016, a committed minority can be the ticket to success so long as your opponents divide the opposition vote.

Sanders’ opponents have done just that: All agree that some among them should quit the race, but none believe that he or she should be the one to do it. Over the last several months, they compounded Sanders’ advantage by largely deciding not to challenge him, mostly giving him gentler treatment than his rivals endured.

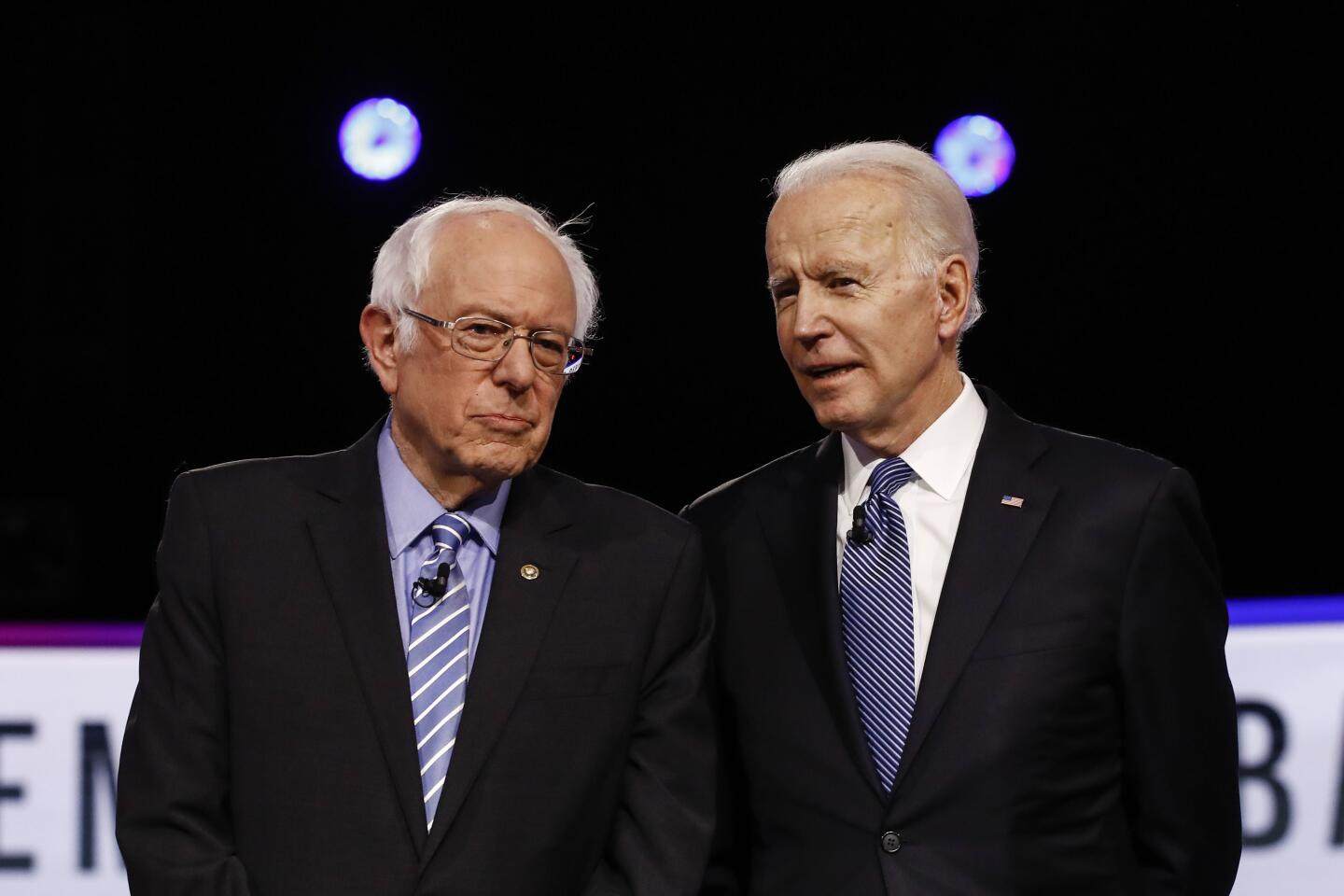

Former Vice President Joe Biden, as the presumed front-runner for much of the year, came under sustained attack during several debates. Those criticisms and his sometimes-halting responses clearly damaged his campaign.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, whose standing rose steadily last spring and summer, got intense pressure in the fall to specify how her proposed healthcare plan would work — and how she would pay for it — even as Sanders largely skated by with bland admissions that he hadn’t put forward any similar accounting.

Other candidates, like California Sen. Kamala Harris, endured scrutiny over previous parts of their careers — years as a prosecutor in her case. That eventually helped push her out of the race.

Sanders drew less of that attention because, until this week, none of the others saw him as their principal rival.

Many Democratic strategists subscribed to the widespread belief that support for the Vermont senator had a natural ceiling. Sanders’ ardent followers would not desert him, but other voters would not turn to him, they reasoned. Attacking him would just anger his supporters, with little chance of benefit, they thought. The wise strategy, they said, was to leave Sanders on an island of the party’s left and focus on winning the much larger continent of the center.

Sanders’ crushing victory in Nevada demolished those theories. He burst through his presumed ceiling and won 34% of the first round of votes in the party caucuses and nearly two-thirds of the state’s convention delegates.

Perhaps as important, Sanders demonstrated in Nevada that his claim of support from Latino voters was real and that he had begun to make inroads among African American voters as well, addressing one of the chief weaknesses of his previous run for the nomination.

That set off panic among many Democratic elected officials, especially those from centrist districts, who do not relish the prospect of running with Sanders at the top of the ticket.

Meanwhile, the Vermont senator boosted his efforts in South Carolina, looking to land a blow that could end Biden’s chances even before Super Tuesday, and stepped up his campaign both in Massachusetts, where polls show he could beat Warren on her home turf, and Minnesota, where he might be able to do the same to Sen. Amy Klobuchar.

Those prospects forced rivals to suddenly reorient their debate strategies.

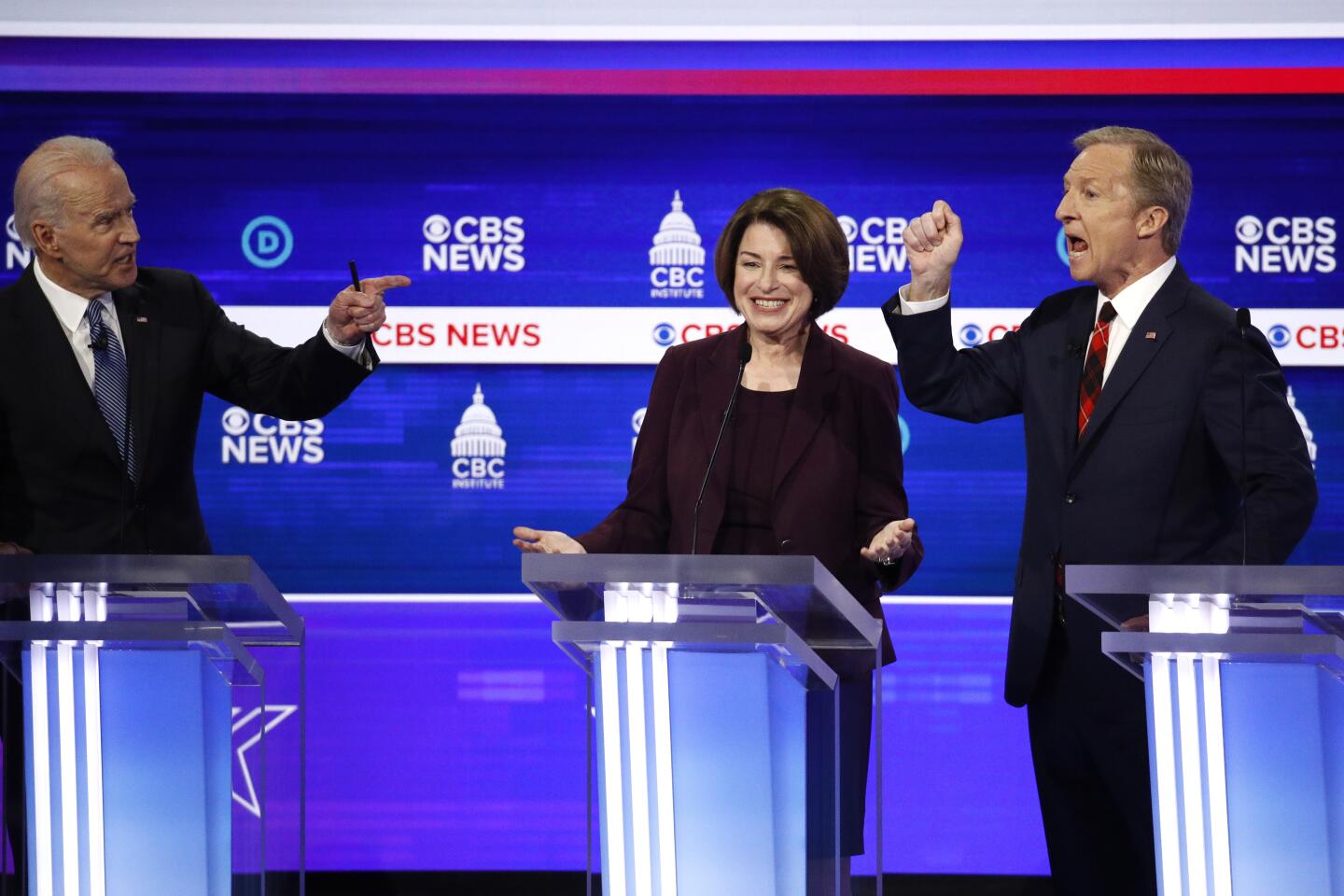

In the debate’s opening minutes, Bloomberg accused Sanders of being Vladimir Putin’s favored Democrat, saying the Russians hope he will deliver a second term to Trump. Biden blamed him for supporting legislation backed by the National Rifle Assn. that gave gun manufacturers immunity from certain lawsuits.

Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., charged him with not leveling with voters about how he would pay for his programs. Klobuchar said Sanders offered “broken promises that sound good on bumper stickers.”

Even Warren, who spent most of the last year in an ultimately self-defeating effort to prevent any daylight between her positions and those of Sanders, got into the act. She sniped at his minimal record of accomplishment in Congress, saying that she and Sanders both want big, progressive change but that only she was willing to be “someone who digs into the details to make it happen.”

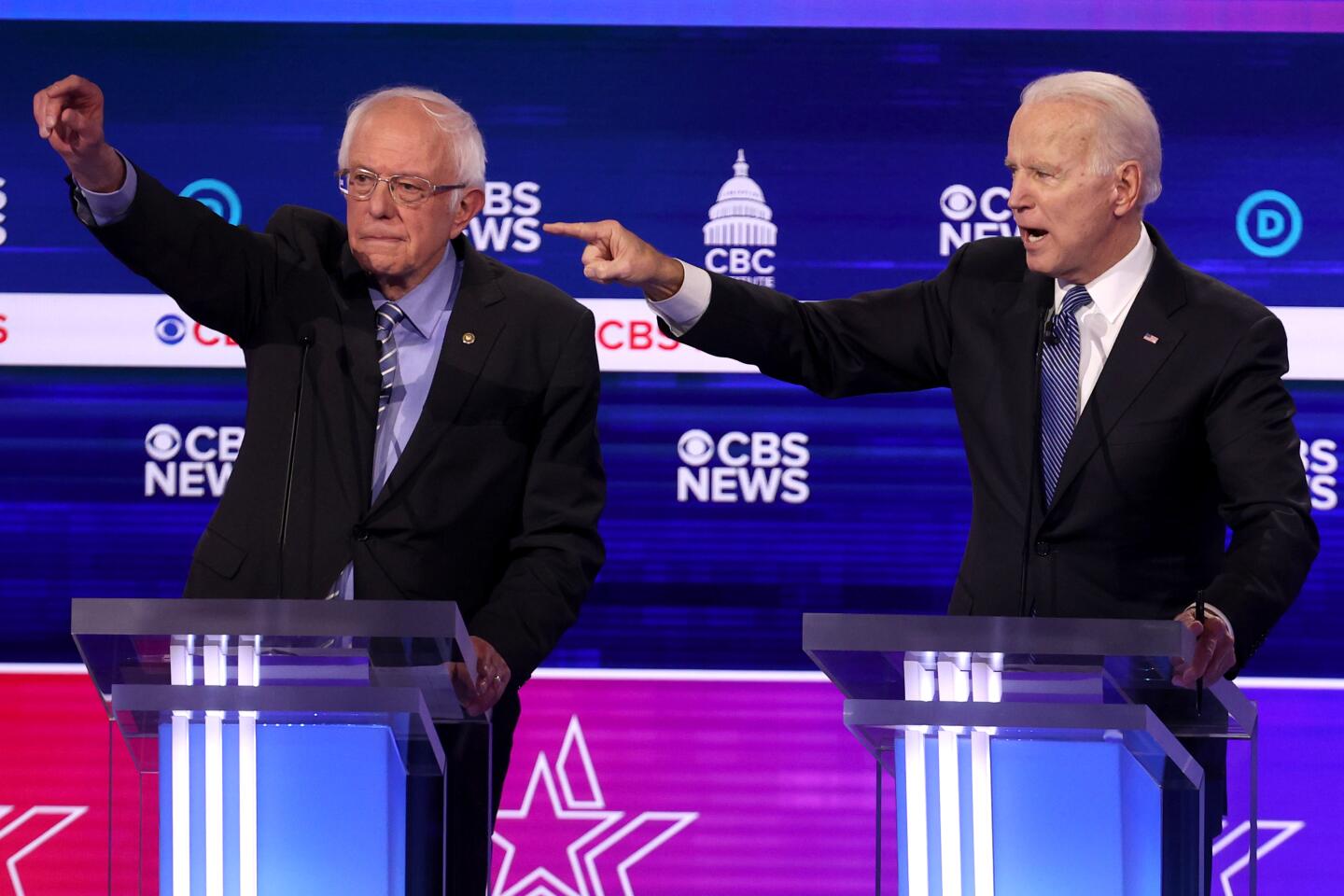

Rival candidates accused Sanders of being too tough on President Obama and too soft on Fidel Castro. They warned that his signature “Medicare-for-all” plan would force millions of Americans off their current health plans. And they repeatedly said that having him at the top of the Democratic ticket would potentially cost the party control of the House.

Sanders, of course, had ready responses to most of the accusations. One advantage of his ideological consistency is that the senator has had four decades to hone the defense of his positions. Still, had Sanders endured such a sustained barrage earlier in the campaign, he might not be in such a commanding position today.

The exchanges clearly laid out the risks — and the potential rewards — of the sharp left turn that a Sanders nomination would represent. Over the next week, with voting in South Carolina on Saturday and 14 states, from Maine to California, on Tuesday, we’ll see if the critique of Sanders persuades voters or whether it was just too many saying too little, too late.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.