Black men killed by police – what did Kamala Harris do about it?

- Share via

Kamala Harris was distraught as she stood before an audience one morning in July 2016. In the previous three days, violence involving police had rattled the nation.

Officers had shot and killed one black man in Baton Rouge, La., and another in his car outside Minneapolis as his horrified girlfriend and her toddler watched. At a protest against those shootings, a sniper had killed five Dallas police officers.

“I have to tell you, my heart is breaking,” Harris said at a meeting on racial bias in policing. Her voice wavered.

“As a prosecutor, my heart is breaking. As the top law enforcement officer in this state. And as a black woman.”

Harris, then California attorney general, paid tribute to officers whose families pray they stay out of danger. She also said she’d never known a black man who wasn’t racially profiled or unfairly stopped.

It was an unusually frank acknowledgment of the forces pulling her in opposite directions in the two years since police killings of black men had set off demonstrations across the country and fueled the Black Lives Matter movement.

Seeking to reconcile the competing demands of police and civil rights groups, Harris tried to avoid inflaming either side. That relatively safe approach has left her open to criticism that she could have done more to lead California’s efforts to limit police use of lethal force.

Harris did make tangible advances in police accountability. She focused on programs inside the attorney general’s office, drawing praise from civil rights advocates and scant resistance from law enforcement.

At the same time, Harris, the state’s first black attorney general, steered clear of the legislative brawls over bills on policing, including what became a groundbreaking law to curb racial profiling. Harris also rejected pleas by civil rights activists to investigate deadly police shootings of young black men in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

“She is maybe a modest reformer, and that’s fine,” said Anne Weills, an Oakland civil rights attorney. “But I don’t think that means she is particularly progressive. She doesn’t look at the big picture about how to make structural change.”

On July 8, 2016, the Racial and Identity Profiling Advisory Board met to begin its work under Assembly Bill 953, focusing on eliminating racial and identity profiling in law enforcement.

For months, Harris has been fending off accusations, most recently in a debate Wednesday, that she did too little to fight racial bias in the criminal justice system.

Harris told The Times she was frustrated by the slow pace of change, but pointed to progress made during her tenure.

“You’d be hard pressed to find any other attorney general in America who at that time was doing the kind of transformative work that we did,” Harris said.

Harris had been attorney general for nearly four years when a white police officer shot and killed Michael Brown, an 18-year-old black man in Ferguson, Mo. The shooting on Aug. 9, 2014, reshaped the politics of race and law enforcement in America.

Video of Brown’s body, left face down in the street in a pool of blood for four hours, went viral on social media. Over the next several days, images of white cops in military vehicles firing tear gas and rubber bullets at mainly black protesters came to symbolize police violence against African Americans.

Police shootings became major news in the months that followed as they were captured in smartphone videos that spread nationwide.

“The death rate from police use of lethal force has been stable for a long time,” said Franklin Zimring, a criminologist and law professor at UC Berkeley. “What happened with Ferguson … was people started to notice that these things kept happening.”

Civil rights groups pressed for new limits on police power. Law enforcement, feeling besieged, fought many of the proposals.

For Harris, the timing was difficult. Police unions had overwhelmingly opposed her when she first ran for the job in 2010, in part because she declined to pursue the death penalty against the killer of a San Francisco police officer, Isaac Espinoza, when she was the San Francisco district attorney. She labored hard to secure their overwhelming support in her run for reelection.

“She had to walk a fine tightrope,” said Brian Marvel, a San Diego police officer and president of the Peace Officers Research Assn. of California, the state’s top police advocacy group.

But civil rights advocates also set high expectations.

“We always hope that because you look like us, you talk like us, you walk like us, you come from where we come from — that you’re not just reading about this in the news. You know there is a war being waged against black bodies,” said Cat Brooks, an Oakland activist who thought Harris fell short.

California lawmakers put police accountability high on their agenda after Ferguson. Among the most contentious bills was one pushed by civil rights organizations to collect data on the race of everyone stopped by police statewide to shed light on racial profiling.

Police groups — still a powerful political force in a state that has only recently tempered its strict law-and-order culture — resisted the bill, arguing it would be too burdensome.

Harris declined to take a position. After Jerry Brown, then governor, signed the bill into law, Harris won credit from civil rights groups for drafting strong rules putting it into effect.

Bill Lockyer, a former state attorney general, said Harris avoided battles in the Capitol, just a few blocks from her Sacramento office, and concentrated instead on running her own agency.

“I saw it as a general reluctance to have an active legislative role,” said Lockyer, a onetime state Senate leader who remained closely engaged in lawmaking as attorney general.

Daniel Suvor, Harris’ chief policy advisor at the time, said her preference was “to work directly with law enforcement and the civil rights community to get things done as opposed to engaging in superfluous dialogue.”

“She had to walk a fine tightrope.”

— Brian Marvel, president of the Peace Officers Research Assn. of California, on Kamala Harris

Harris’ authority over police practices was limited. In a state with nearly 80,000 police officers, the attorney general employed only about 300 — special agents who investigate healthcare fraud, gun violations and drug crimes. By November 2015, all agents in the field were equipped, on Harris’ order, with body-worn cameras.

Some advocates were seeking mandatory body cameras for nearly every officer in California. They tried unsuccessfully to pass a bill to create a statewide standard for their use. Harris spurned the proposal, saying she opposed a “one-size-fits-all approach.”

Another Harris project was anti-bias training for law enforcement agencies statewide, which proved popular. More than two dozen agencies participated in the first course. It remains part of the state’s formal officer training.

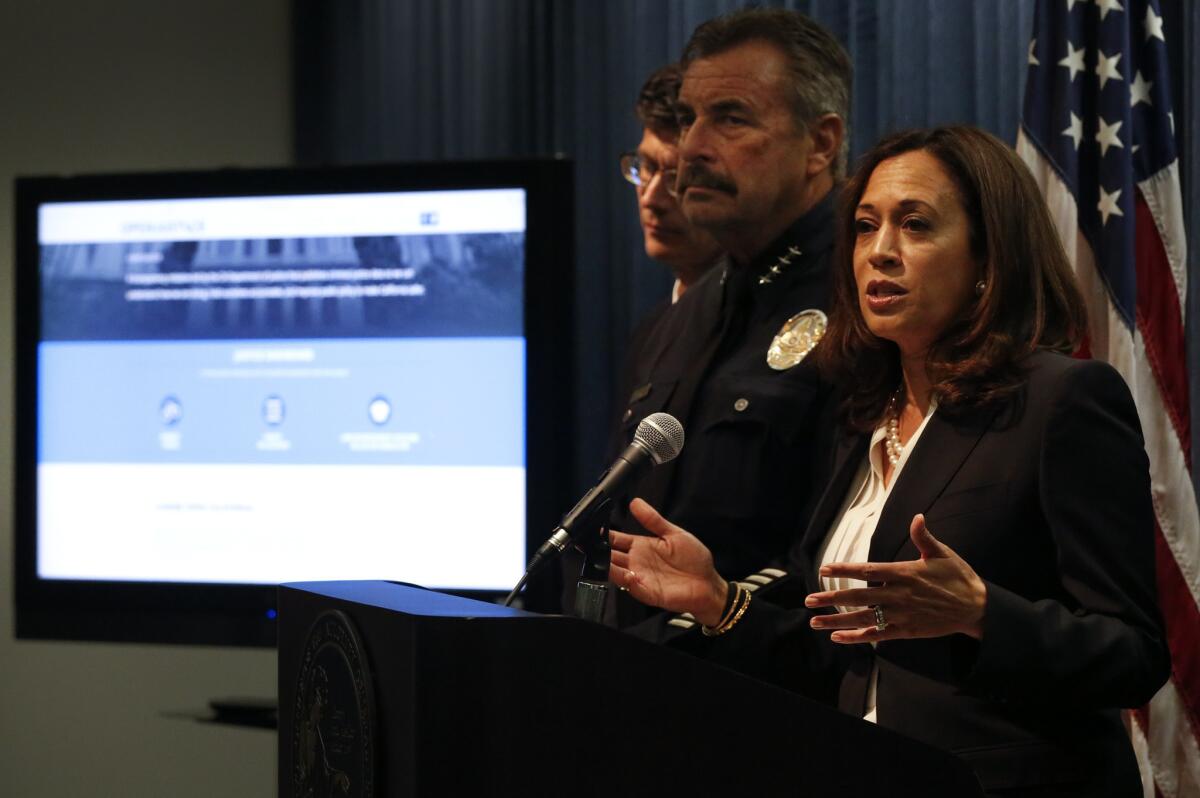

Harris’ signature achievement from this period was Open Justice, an online portal that, for the first time, made a wide array of criminal justice data available to the public, including tallies of deaths and injuries in police custody.

“She saw there was so much emotion and anecdote around the criminal justice reform conversation, and she wanted to inject data, facts and evidence into the conversation,” Suvor said.

It was the rare initiative embraced by both police and reform advocates.

“That was really, really helpful to the movement, because there was no place that we could look at in-custody deaths at the hands of law enforcement prior to that,” said Melina Abdullah, a Black Lives Matter organizer who chairs Cal State L.A.’s Pan-African studies department.

Harris was less successful in dodging political fallout when it came to calls for state investigations of high-profile shootings. Civil rights advocates viewed local prosecutors as inherently compromised in cases against police they worked closely with every day.

State intervention in local cases was a fraught issue for Harris. In 2004, Lockyer, then attorney general, had second-guessed her refusal to seek the death penalty for the killer of Espinoza, opening his own investigation into her decision. (He ultimately sided with Harris.)

“There’s no question that has influenced and did influence my perspective on this,” Harris said, adding she believed local officials are best held accountable by voters.

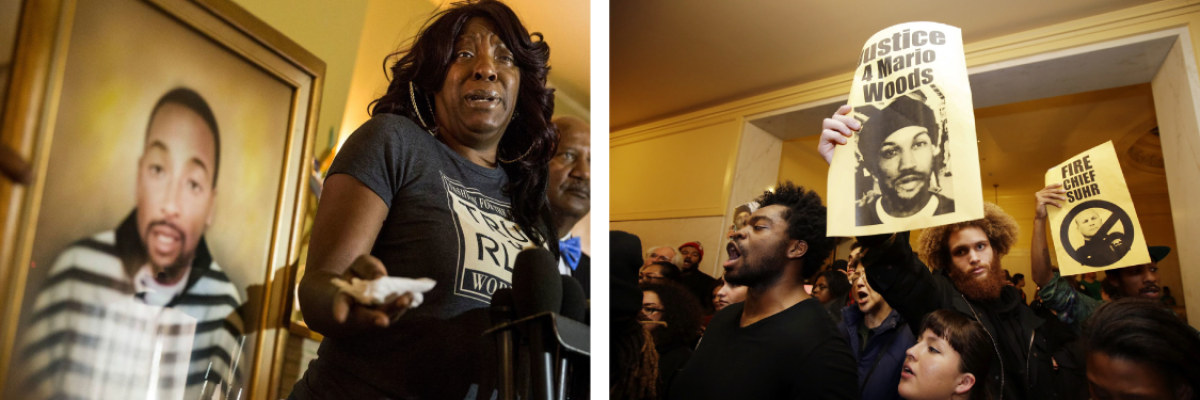

Community activists urged Harris to investigate two high-profile police shootings in California — Ezell Ford’s death in Los Angeles in 2014 and the 2015 killing of Mario Woods in San Francisco — but she demurred, saying she lacked legal grounds to overrule local prosecutors.

“I wouldn’t even say disappointed is a strong enough word for how we felt about how she did as attorney general,” said Kim McGill, an organizer with the Youth Justice Coalition.

Critics suspected a political motive behind Harris’ stand against state probes of the L.A. and San Francisco police shootings.

“When she was running for attorney general, she was already running for president,” Weills said. “It’s a very calculated process. For her to start to alienate the whole law enforcement establishment by taking on these investigations … it might have destroyed her career.”

A 2015 bill, which failed to pass, would have required the attorney general to appoint a special prosecutor to take on cases involving police use of deadly force. Harris decline to support it.

Yet Harris did not always take a hard line against state probes of local police misconduct. She privately asked the governor for money to create teams of prosecutors to conduct such investigations in jurisdictions that consented to them. Brown refused, she told The Times.

After she won election to the U.S. Senate, and in her final days as attorney general, Harris opened civil rights investigations into the Kern County Sheriff’s Office and the Bakersfield Police Department, which remain ongoing under her successor, Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra.

Now, as she runs for president, Harris has more forcefully backed independent investigations of police wrongdoing. She has promised the U.S. Justice Department would pursue more robust oversight of racial bias in police departments nationwide. She has also vowed to push legislation to end racial profiling.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.