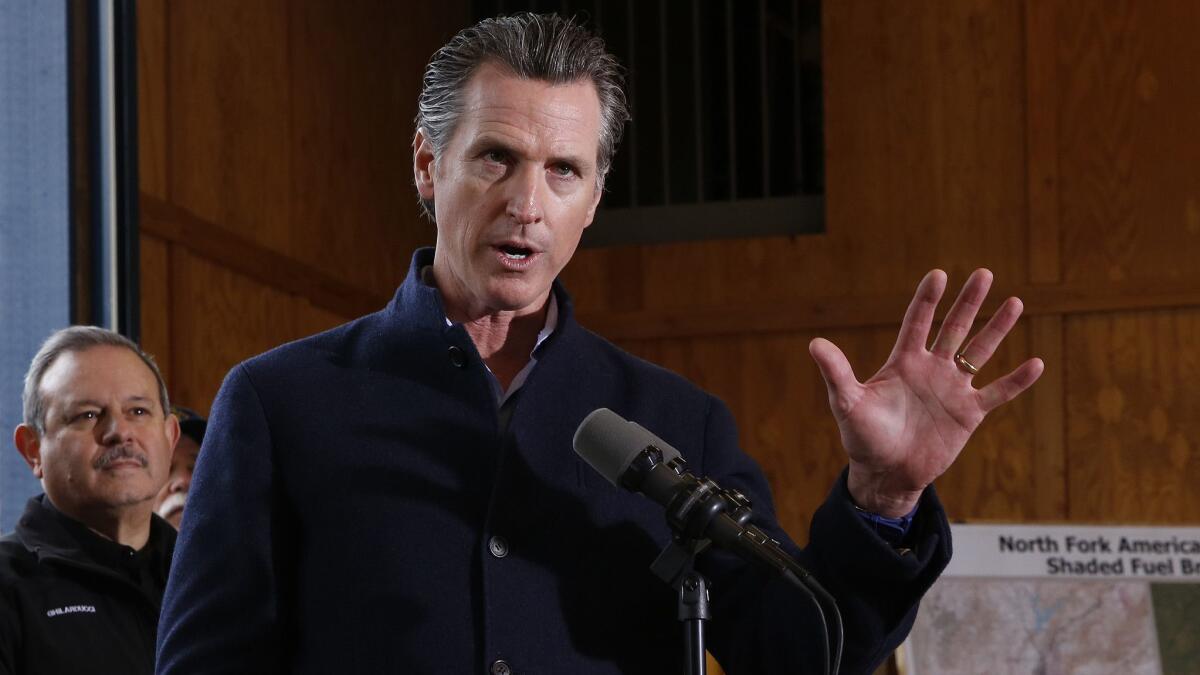

Newsom tested right out of the gate with teachers’ strike and PG&E crisis

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Just hours after the warring parties in the Los Angeles teachers’ strike hailed Gov. Gavin Newsom for helping end the weeklong labor impasse, activist Erin Brockovich stood on the south steps of the state Capitol and demanded that the governor and state lawmakers hold Pacific Gas & Electric Co. accountable for sparking deadly wildfires.

“I think he has an opportunity here to step up and, honestly, be the right leader when it comes to Pacific Gas & Electric. They’ve gotten too many passes in the past,” said Brockovich, made famous by the movie about her legal battle with PG&E over cancer-causing pollution in the small farming town of Hinkley.

Her challenge offered a glimpse of the unrelenting pressure the Democratic governor faces as he settles in to lead a state that overflows with natural disasters and man-made emergencies. In just two weeks in office, Newsom displayed his political savvy and instinct for self-preservation when faced with his first two major crises: the weeklong Los Angeles Unified School District teachers’ strike and the ongoing threat of bankruptcy for California’s largest utility.

When Newsom was almost immediately confronted with the two predicaments after taking office Jan. 7, his newness to the job allowed him to address both without risking the perception that he contributed to or had ownership of the issues.

“Newsom’s got the best of all worlds now,” said Sean Walsh, a senior policy advisor to former Republican Govs. Pete Wilson and Arnold Schwarzenegger. “He’s rolling, rolling, rolling in money right now with the budget surplus, and he’s got problems that aren’t seen as his problems. So he can be seen as a problem solver.”

On the first day of the L.A. strike, Newsom offered only a muted response by calling on union leaders and school district officials to continue negotiating. The governor, who was endorsed by teachers unions in the 2018 gubernatorial election, told reporters he was engaged in “informal” talks but would not directly intervene unless asked by both sides — a request made by L.A. schools Supt. Austin Beutner, but not by the union.

But behind the scenes, Newsom and his staff played a pivotal role in helping to resolve the strike. Newsom was on the phone continually with Beutner and Alex Caputo-Pearl, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, signaling his administration’s support for a number of underlying issues including increased funding for special education programs and community schools, which provide social services to students and families, as well as enriched academic programs, according to sources familiar with the negotiations.

The week before the strike, Newsom released a new state budget that included a one-time, $3-billion payment to reduce the pension liabilities of school districts across California, freeing up more money for campuses including those in Los Angeles and Oakland, where the potential for a teachers’ strike still simmers.

“The governor and his team played an important role in getting this solved. He was in constant contact with both Alex and myself in helping find solutions, so many of which the state must play a role in,” Beutner said in a statement Wednesday. “He spoke very clearly about his commitment to public education and his willingness to work with us on the long term solutions we need to make it better for students and educators.”

Caputo-Pearl said Newsom also emphasized his support for legislation to increase transparency and accountability at charter schools, a crucial issue to the teachers union, which believes the growth of such campuses in Los Angeles is an existential threat to the public school system, draining funds and enrollment. Caputo-Pearl added that a possible moratorium on new charter schools was a “big part of the discussion” during the last five days of negotiations.

During his campaign for governor, Newsom advocated increased transparency for charter school operations and finances. Wealthy charter school backers also spent $23 million attacking Newsom and supporting one of his Democratic rivals in the primary, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa.

Newsom, who has enjoyed strong political support from unions, has nevertheless been on both sides of labor disputes and contract negotiations, particularly during his two terms as mayor of San Francisco.

In addition to negotiating with San Francisco’s public employee unions throughout his time in the mayor’s office, Newsom also intervened in labor disputes outside the city’s purview, including a protracted two-year impasse between hospitality workers and 13 San Francisco hotels as well as threatened strikes by teachers and school janitors in the Bay Area city.

“One thing that the people of California have in Gov. Newsom is not only experience, he has the credibility to go in and mediate these issues,” said Steve Kawa, Newsom’s chief of staff while he was mayor of San Francisco.

In the hotel labor action, Newsom made good in 2004 on a threat to join union members on the picket line outside the Westin St. Francis hotel after management locked the workers out and refused to agree to the then-mayor’s call for a 90-day cooling-off period. And as lieutenant governor in 2013, Newsom interjected himself into a four-day regional rail strike in the Bay Area, talking to both sides in the negotiations even though he had no real authority to intervene.

Coverage of California politics »

But wading into the Los Angeles teachers’ strike did not come without peril. If Newsom alienated the teachers union, he risked losing the backing of one of his strongest bases of political support: organized labor. If the governor agreed to open the state’s checkbook to increase year-after-year funding for public schools — allowing L.A. Unified to meet the union’s demands to reduce class sizes, increase pay and expand support staff — other districts around the state would expect the same, dramatically increasing state spending.

“For politicians getting involved, almost everything bad happens to you. You become the target of both sides,” Walsh said.

When Orange County declared bankruptcy in the mid-1990s after suffering $1.7 billion in losses on high-risk investments, then-Gov. Wilson rejected the idea of a state bailout, fearing other municipalities across California facing fiscal troubles would come to Sacramento with their hands out, Walsh said.

“Sometimes it takes a lot more courage to say no,” Walsh said.

The Newsom administration now must weigh what level of response it should take with Pacific Gas & Electric, balancing the rights and well-being of wildfire victims, ratepayers and the fate of a utility that provides electricity and natural gas to roughly 16 million people in Northern and Central California. Legislative leaders have said they have no interest in bailing out a utility that, among other things, was found criminally liable for a gas pipeline explosion that killed eight people and destroyed a residential neighborhood in San Bruno in 2010 and was accused by the state Public Utilities Commission of falsifying pipeline safety records.

“We’ve been in constant contact, including a few hours ago, with representatives from PG&E, including the interim CEO, and we’re just staying in close contact,” Newsom said Thursday. “We aren’t making any commitments in private, or asserting any point of view in private that I’m not making here in public.”

Just days after PG&E officials said the utility intended to file for bankruptcy over the potential liabilities it faces due to the state’s wildfires, Newsom announced that his chief of staff, Ann O’Leary, would lead a task force to determine the next steps for the state. Newsom offered assurances that the “lights will stay on” and that PG&E would be held accountable.

“PG&E, with respect, has not been a trusted player in the past,” Newsom said just days after the utility made its bankruptcy announcement. “They have admitted knowingly misleading regulators in the past — very recent past. That is simply unacceptable. I can assure you when it comes to our engagement with PG&E, it is trust but, dare I say, verify. And let me underscore ‘verify.’ ”

As with the teachers’ strike, Newsom has said he’s been in constant contact with the parties involved. A spokesperson for the Newsom administration said the governor’s internal PG&E task force has been meeting every day to plan for all contingencies.

Attorney and former state lawmaker Noreen Evans, whose legal firm represents 4,000 wildfire victims, said Newsom must do everything in his power to ensure PG&E does not declare bankruptcy. If the utility does, Californians who have lost loved ones and everything they own will get stiffed, she said, because federal bankruptcy courts put them at the back of the line of all the creditors to be paid.

Evans acknowledges that Newsom has no direct legal authority to prevent the utility from declaring bankruptcy or to ensure the victims are fairly compensated. That will mostly be in the hands of a bankruptcy judge, the California Legislature and the Public Utilities Commission, whose members the governor appoints, she said.

But Newsom didn’t have legal authority in the Los Angeles teachers’ strike either, and that didn’t stop him, she said.

“The governor is the leader of the state of California,” Evans said. “So if he were to announce some blueprint to get to the place where the victims get compensated and PG&E gets reined in, the Legislature is going to work on that.”

Times staff writers Howard Blume and Taryn Luna contributed to this report.

Twitter: @philwillon

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.